Looking through the information regarding William Mossman’s workshop at the corner of Cathedral Street and North Frederick Street, the paucity of knowledge becomes apparent. In Gavin Stamp’s ‘List of Works’ in Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson1, the date given for its construction is 1854, presumably based on a reference in the Edinburgh-based Building Chronicle of that year2. Ronald McFadzean’s earlier assessment3 dates it to 1856, while historian Frank Worsdall thought it dated to 1849-50.

William Mossman (1793-1851) was born in West Linton, Peebleshire, trained in London, where he worked for Sir Francis Chantrey, before moving to Edinburgh in 1823. He then relocated with his family to Glasgow, managing David and James Hamilton’s marble business and working as a sculptor at James Cleland’s statuary yard at 5 Cathcart Street. The yard was at what is now the eastern end of Sauchiehall Street, where the Cleland Testimonial building was constructed in 1836 and for which Mossman carved a heraldic shield and lion heads, now lost.

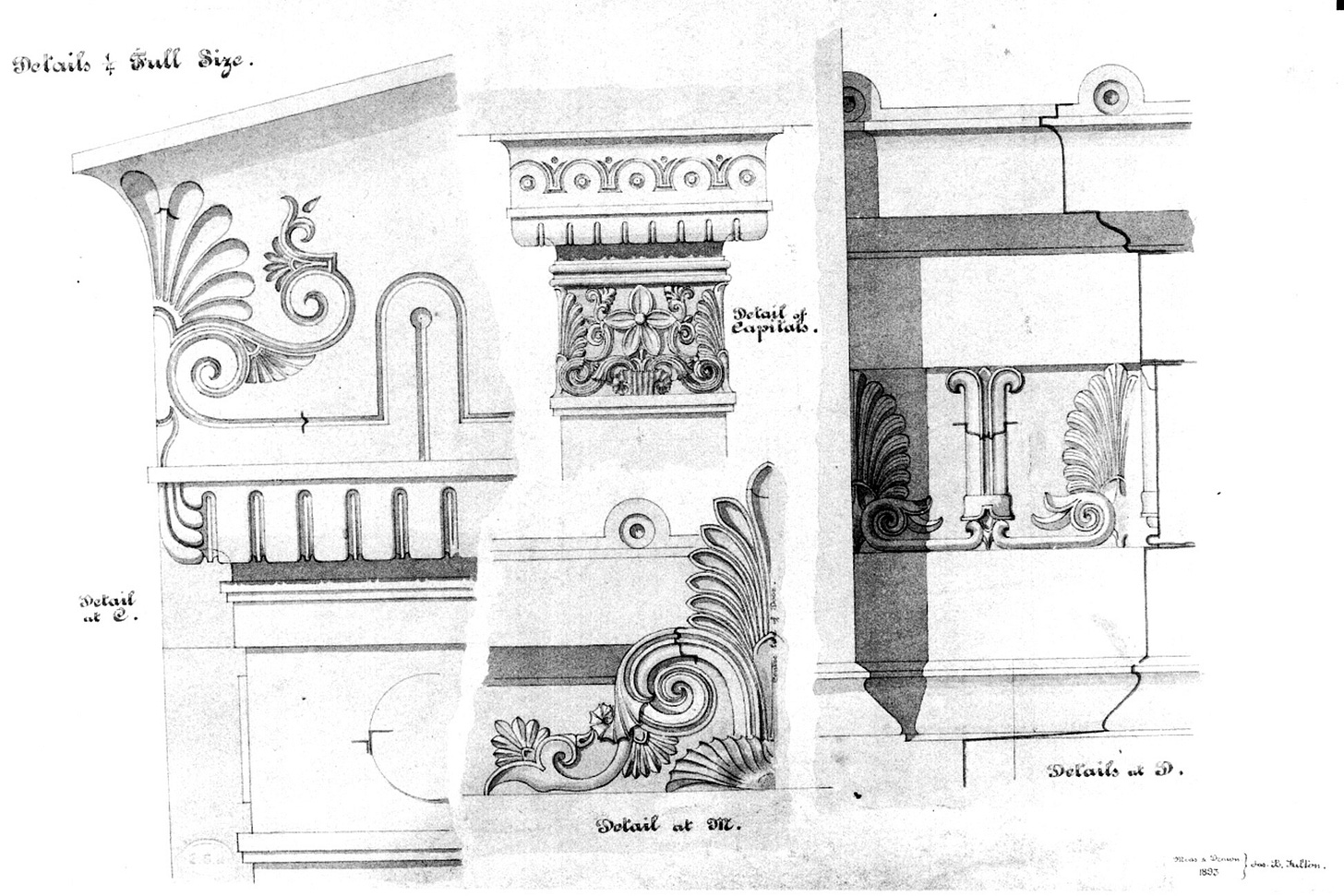

By June 1831, Mossman was listed in the Glasgow Post Office Directory on his own account as a monumental sculptor with a studio at 172 West Nile Street. Mossman stayed there until around April 1845:

Mossman probably needed larger premises to cope with the volume of sculpture his workshop now involved. In mid-June, Free St John’s Church in John Street opened, with four exterior heads by John Mossman and eight busts of noted divines. In August, a monument at Sighthill, designed by London architect Robert Wallace, was unveiled, described as ‘certainly never surpassed anywhere - not even in the far-famed Père La Chaise’, followed by a bust of Marshall Graham for Glasgow Police Board4. That year, there was also the Necropolis monument to the Polish patriot Lt Joseph F. Gomoszynski, carved with his coat of arms. By early 1846, the studio had completed Lockhart’s monument, ‘the gem of the Necropolis’ and a bust of Mause Headrig (from Old Mortality) for the Scott Monument5.

Dating the studio

What were they moving into if the Mossman studio and household were relocated to North Frederick Street? After all, this was a home as well as a workshop, for himself, his wife Jean McLachlan, whom he had married in Glasgow in 1816, and their three sons (a son and two daughters had died before 1841). It seems unlikely that either the family home or the business would have stayed on site while Thomson built a new home and workshop around them. Is it not possible that this is an unexpectedly bravura work by Thomson carried out while finishing up as senior draughtsman to John Baird I, or even an independent job pre-empting his partnership with John Baird II?

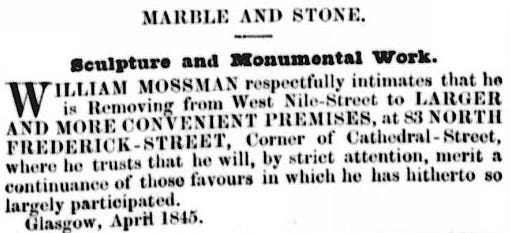

One reason for thinking so relates to the building itself. As mentioned, the site included a family home, in which William and Jean were later joined by their daughters-in-law and grandchildren. The home was quite possibly the premises to the northwest of the sculpture yard, bounded in red. I suggest this could have been a two- or three-storey building, with a single-storey entranceway (hence the line between what I take to be the dwelling and the entrance), possibly connecting also to the studio fronting North Frederick Street, bounded in blue. Both these buildings appear unchanged when the southern portion and yard had been replaced by other buildings (see below).

A second reason for thinking the studio is earlier than 1854 is mapping. While not entirely reliable at this time, J & D Nichol’s 1844 map shows the area north of what would become Cathedral Street entirely undeveloped (named as ‘College Hill’).

By 1847, however, Allan & Ferguson’s map does show buildings in place, and while the detailing is not fully consistent, the mapmakers might have been more aware of structures fronting streets than what lay behind.

If the studio does date to 1845, then the work would have been commissioned by William Mossman senior, probably in partnership with his sons and after discussion over how much space was needed and the internal arrangements, especially if the family were living next to, rather than over, the shop.

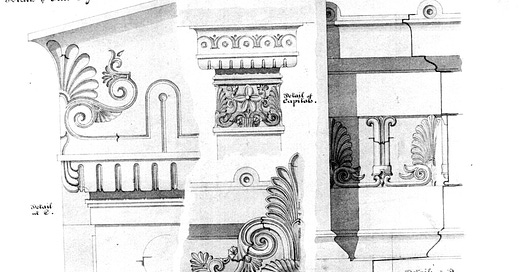

If the traditional later date of 1854 is taken, then the need for the new studio would have come from the sons, perhaps seeking to reinforce their pre-eminence as sculptors and stone workers. Also, the style of the capital shown in Fulton’s drawing at the top of this article is entirely consistent (although the details are different) with those used at Holmwood in 1856. But if so, the building work would have made the site a noisy one for the family and inconvenient for the workers, and there is no evidence that either the family home or the workshop were relocated at this time.

Resolving the layout

In 1888, architect Thomas Gildard described the outside of the studio:

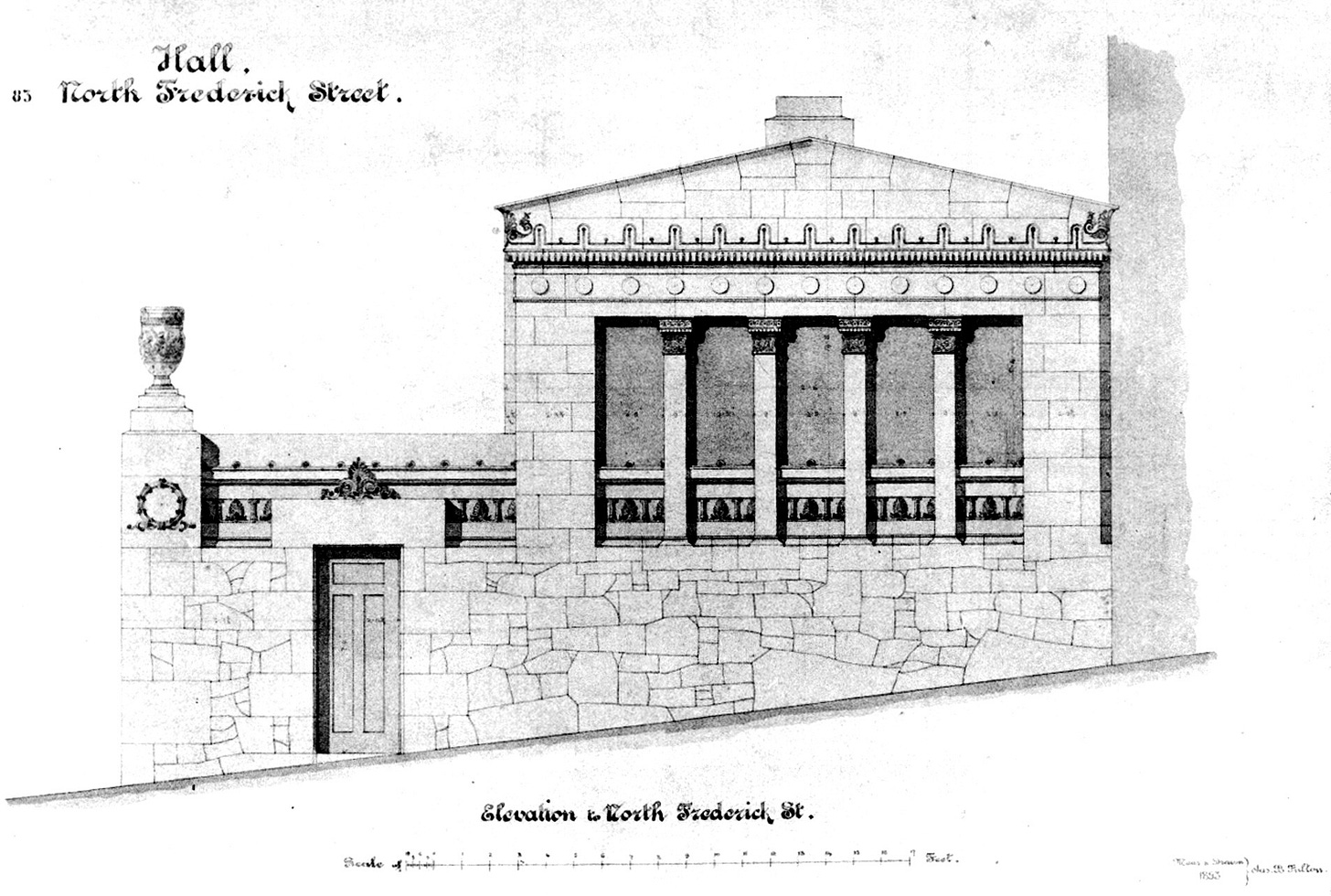

The site, the corner of two streets, one of which is level, the other having a considerable inclination, is taken advantage of with consummate skill as regards both artistic design and utility. Along the level street the walling is of cyclopean masonry, pierced by a doorway which, from its sill being on a level with the surface within, serves the purpose of ‘bank’ loading, and on each side of it, by three openings, having broad dwarf pilasters between them, also on each side of the doorway, the extreme piers being of cyclopean work, part of the general walling. On the inclined street the composition is in four parts: the first, a continuation of the cyclopean wall, with its somewhat horizontal openings and their dwarf pilasters; the second, the gateway, with its piers ‘growing’ from the general walling: the third, the screen between the gateway and the studio proper, with its doorway crowned by a block cornice and acroterion, and having a honeysuckle-and-lotus enrichment extending from each end of this cornice; and the fourth, the studio proper, composed of four pilasters and two extreme piers carrying a block pediment, between the pilasters a dado on a level with, and continuing the honeysuckle-and-lotus enrichment on each side of the door, the whole standing on a cyclopean basement6.

Commenting on Gildard, McFadzean argues that forming an image of the actual building is impossible. Still, it seems likely that the Cathedral Street frontage consisted of a solid wall with a blanked-off doorway flanked by false or actual window openings. Gildard appears to be indicating that the floor level within the yard had been raised against the inside of the Cathedral Street wall to allow for a more level entry into the yard for loaded carts from the steeply inclined North Frederick Street. Against the interior of this wall would be where uncut stone was probably stored. Small wonder Cathedral Street needed ‘cyclopean masonry’.

There appears to have been one entrance for vehicles, shown by the roadway entrance above, and a single entrance for visitors, workers (and presumably family members). Of James B Fulton’s two drawings of 1893, the only ones showing any of the studio detailing (one is shown at the head of this article), the North Frederick Street aspect (below) shows the northernmost gate pier, the pedestrian doorway to the right allowing entrance into the yard or the studio, and the studio itself as Gildard terms it (or ‘Hall’ as shown).

Extrapolating the height of the gate pier to a southern counterpart of equal height and then extending the top of the cyclopean wall seen above to Cathedral Street suggests that the wall height at the latter point must have been something of the order of 15 feet or more. This is also suggested by the massing of the current building on the site, George Arthur & Son’s 1913-14 Edwardian Baroque Orange Halls (below, subsequently the Catholic Apostolic Church, now the Glasgow City Church), so probably to the top of the stone balcony on the Cathedral Street front.

Moving out and on

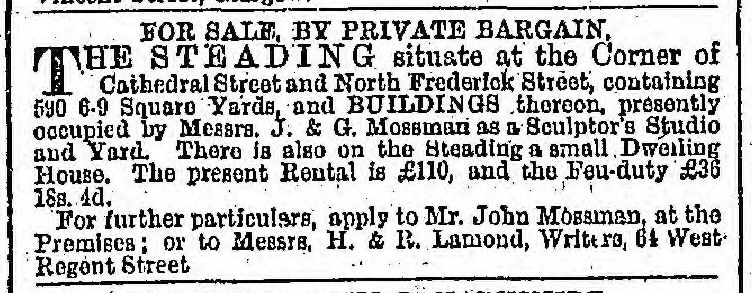

In April 1851, William Mossman senior died at 83 North Frederick Street. In 1863, George Mossman died (he was living in nearby Grafton Square); in June 1864, Jean McLachlan died at North Frederick Street. By September 1868, it seems likely that the company’s workload, as much as the family, had again outgrown the site. By now, William’s eldest son John was married with a son, George had left five children (the eldest, thirteen) and a widow, while William junior, who was living at 52 Dumbarton Road, had a wife and two daughters, a son and daughter having died young.

A year later, the North Frederick Street yard and house were still in use, but granite polishing works had been opened in nearly Mason Street. One reason for the delay might have been the cost of clearing the Cathedral Street site for rebuilding. Only by 1875 had John Mossman moved out, to 21 Elmbank Crescent, with all the firm’s works now based at Mason Street (this, seen below in 1952, is where the noted photograph showing the statues for St Andrew’s Halls was taken).

When Gildard spoke in 1888, he referred to the Mossman studio in the present tense. By the time of the 1893 Ordnance Survey, the sculpture yard, with its cyclopean walls to the south had been replaced, although the northernmost buildings remained.

How long did the house and studio remain? Even the 1835 Ordnance Survey shows buildings with the same ground plan on the site, after the construction of the Orange Halls. Today, the site is an entrance to the rear of new housing that has replaced the tenements to the north, shown in the map below.

G Stamp, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, London, 1999

Building Chronicle, 26 July 1854 (The only available copy in the UK of the Building Chronicle for 1854 appears to be in the British Library, which I have yet to visit, so the construction dates could change depending on what that article says)

R McFadzean, The Life and Works of Alexander Thomson, London, 1979

Glasgow Citizen, 14 Jun 1845; Glasgow Courier, 16 Aug 1845; Glasgow Chronicle, 10 Sep 1845

Glasgow Courier, 18 Feb 1846; Glasgow Herald, 6 Mar 1846

Quoted in McFadzean, op. cit