Who were the Coopers?

Tracking ‘Greek Thomson’s maternal family, with reference to Lord Byron, a demanding music-master, and an Aberdeen goldsmith

Alexander Thomson’s mother

When Elizabeth Cooper married John Thomson, bookkeeper at the Ballindalloch Cotton Works in Balfron in 1801, she did so as the sister of John Cooper, the recently arrived Burgher minister, and as someone whose claim to fame was a childhood connection with Lord Byron. As JEH Thomson (Alexander’s nephew) blithely writes:

As a girl she had been at school with Lord Byron, the future poet being then known as ‘the laddie wi’ the feeties’. He was living with his mother in comparative poverty, his father, Captain Byron, having ‘squandered the lands o’ Gight awa’1.

Byron’s mother, Katharine, had become hereditary 13th Laird of Gight in Aberdeenshire after her father died in 1779. Six years later, in Bath, she met and married Captain John Byron as his second wife but then found herself having to sell her land and title to pay his debts, leaving her with an annual allowance of £150, although this was still a substantial sum. They had travelled to France, and she returned in 1786 to give birth to her son, George Gordon Byron, at 16 Holles Street, London, on 22 January 1788. Mother and child moved to Aberdeen, the Captain travelling from France to borrow more money before returning and dying in France, probably from consumption, in 1791.

Byron and his mother lived firstly in Queen Street, Aberdeen, and then, after her husband’s death, on the first floor of 54 Broad Street, attending St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel2. There were also regular visits to relatives in Banff3. In the autumn of 1792, aged four, Byron was enrolled in a school in Long Acre under Mr ‘Bodsy’ Bowser. In later life, he claimed to have learned little there until the arrival of Mr Ross, a clergyman.

This is probably where Elizabeth Cooper would have first known him; she would have been aged nine and would have known him for two years at most, since in 1794, aged six, he transferred to Aberdeen Grammar School, registered as ‘George Byron [or possibly ‘Bayon’] Gordon’. She might possibly have met him again at dancing classes he attended before he was eight (and where it is said he first met and conceived a passion for his cousin Mary Duff.

Four years later, a great-uncle’s death enabled him to leave Aberdeen as 6th Baron Byron of Rochdale, owner of the somewhat ruinous estate of Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire. From there, mother and son moved back to London to continue George’s schooling and commence his subsequent rise to fame.

Alexander Thomson’s maternal grandparents and uncles

Without firm documentary evidence, establishing parentage is, at best, a matter of informed reasoning. The Rev. John Cooper’s background can be fairly established as the son of George Cooper, an Aberdeen merchant, and Jean Shewan, born there in 1762 and christened in the Burgher church at Netherkirkgate. A brother, Alexander, was born at Dundee in March 1764, but there is no record of Elizabeth’s birth, either under both parents’ names or under George Cooper’s name alone.

Of the Dundee-born brother, Alexander, we know nothing. Although there are several Alexander Coopers in Aberdeen around this time, the only traceable one whose location and dates fit so far was a cooper by trade, living at 26 Cooper’s Court, Netherkirkgate, who died there aged 75 on 13 October 1836. An alternative could be the saddler Alexander Cooper; he may have had a son of the same name who continued in the trade. It may be the father or son who rose to be Deacon of the Incorporation of Hammermen in Aberdeen and Master of the Trades Hospital (the records found so far aren’t particularly clear).

Jean’s father was a mason from Peterhead, but we know nothing else about him. ‘Shewan’ is by far the more common spelling up to 1855; in Peterhead, where the family came from ‘Shewan’ is used twice as many times as ‘Shuan’, although the latter is used in her marriage to George Cooper. By this time, the spelling of ‘Cooper’ as used in the family was standard; going further back, the variations used in Aberdeen vary from this to ‘Couper/ar’, ‘Cowper/ar’ and ‘Cupar’.

To be of age when she married John Thomson in 1801, Elizabeth is unlikely to have been born after 1780. Technically, under Scots law, she could have been married as young as 14, but in practice, marriage at that age was rare, and there would normally be a reference to parental consent in the record of a couple marrying young4. The 31 October 1801 entry in the parish register reads, ‘Thomson Mr John and Miss Elizabeth Cooper both in this Parish entered their names for proclamation of Banns’, with no reference to consent being required. If her birth year is approximately correct, this would mean that her last child, Elizabeth, would have been born when she was approaching or just into her 40s.

Of course, the greater the age difference between Elizabeth and her older brothers, the greater the age at which Elizabeth’s mother would have given birth to her, and Elizabeth may well have been born when Jean Shewan too, was approaching or just into her 40s. However, the age gap could be explained if Jean Shewan had died and her father remarried so that Elizabeth was in fact a half-sister to John and Alexander.

Assuming that all three children are those of George Cooper and Jean Shewan, at this stage, the family tree looks like this:

George Cooper, ca 1728-ca 1804, husband of Jean Shewan ca 1740-ca 1805

Rev. John Cooper, 1762-1821, husband of Susannah Dinwiddie 1765-1822

Alexander Cooper, 1764-?

James Cooper, ca 1767-1840

Elizabeth Cooper, ca 1780-1828, wife of John Thomson 1757-1824.

To some extent, we are reliant on the Memoir for information. Still, since JEH Thomson bases his information on documents to which we no longer have access, as well as conversations with George Thomson, given their joint interest in church matters, we can assume a fair degree of accurate recollection around some issues, at least.

The Memoir states that Elizabeth’s father, George was ‘one of a number who originated the first Secession church in Aberdeen’. This happened in 1747, with parishioners of St Nicholas Church seceding to form Netherkirkgate Burgher Church. The implication is that George was an active participant, not simply taken along with the rest. On that basis, he must have been in his late teens at the youngest, giving an approximate birth date of not later than 1729, making him around 33 years of age when he married.

Referring to George Thomson’s childhood in Balfron, the Memoir states that ‘James Cooper, Mrs. Thomson's uncle, had been in the navy during the great French war, but was now invalided. In his walks he took the younger members of the family under his especial care’. It also reports that George later ‘spoke with enthusiasm of the effect his uncle had on him’.

James Cooper appears to have been born around 1767, although his birth records have not yet been traced. He moved with the family from Balfron to Glasgow in the late 1820s, died from ‘fever’ at 73, and was buried in the Anderston burying ground, where various family members were interred.

There were three periods of war between Great Britain and France in the eighteenth century, the ‘Bourbon War’ from 1778 to 1783, the French Revolutionary Wars from 1793 to 1802, and the Napoleonic Wars from 1803 to 1815, in which Michael Thomson, John Thomson’s second son from his first marriage, was killed. James likely served in either the second or third rounds of war (if not both) before being invalided.

Alexander Thomson’s maternal great-grandparents

Going back another generation, to ‘Greek’ Thomson’s great-grandfather, the records aren’t particularly helpful when looking for George and James being born to the same father in and around Aberdeen, preferably in the same parish, George not after 1729 and James ten years or so either side. However, George and Jean’s son Alexander is recorded in his baptismal entry as named in commemoration of his grandfather, which leaves us with two principal candidates:

James and George, born to Alexander Cooper and Jean Gilreith in Old Machar, Aberdeenshire, in 1724 and 1728.

George and James, born to Alexander Cooper, but with no named mother in Ellon, Aberdeenshire, in 1726 and 1737.

Old Machar, ‘a parish, chiefly without, but partly within, the city of Aberdeen’5 seems a more likely location than Ellon, which is some 16 miles further away.

There were other parents with sons named George and James born in the decades to 1740, but no two have either the same father and mother or even the same father in the same location. There is always the possibility that, as with Elizabeth herself, her father’s birth (or that of an uncle) was not recorded, that any record has been lost, that their births are hidden among the various sons born for whom only the father’s name is given, or even that the place of baptism (which is usually what is shown) changed between one son’s birth and another.

On balance, Alexander Cooper and Jean Gilreith seem the most likely parental candidates, but with no guarantees. Whichever parents are correct, the assumption is that George probably died sometime between 1780 and 1800, possibly as late as July 1804, when a George Cooper is buried in the Netherkirkyard. If that is the case, Jean likely travelled south to live with her son and daughter and, according to one record, died a year later in Balfron.

Alexander Thomson’s maternal great-great-grandparents

Alexander Cooper was a merchant. He married Jean Gilreith in Old Machar in 1721, and they had four sons, at least one of whom died in infancy, George being the youngest.

George’s father, Alexander, died in 1750, his wife nine years later, and both were buried in Old Machar Churchyard.

Alexander Cooper, Alexander Thomson’s maternal 3 x great-father

It is impossible to tell how successful Alexander was as a merchant, but his father, another Alexander, was well-connected. The elder Alexander had three sons, Alexander, John and George, and four daughters, of whom the eldest, Elizabeth, appears to have died young. Of the second, Anna, we know nothing after 1696, the third, Isabel, died unmarried, while the youngest Christian married and bore children.

The witnesses to the sons’ baptisms were all substantial men. For the younger Alexander, these included George Middleton, Principal of King's College, Aberdeen, James Garden, Professor of Divinity at King’s College, and George Garden (James’s brother), minister of St Nicholas. Some also witnessed the baptisms of the other sons, together with John Keith, minister in Old Aberdeen, John Haliburton, ‘civilist’ (Professor of Civil Law) at King’s College and son of the Bishop of Aberdeen, and John Cooper, presumably Alexander’s brother and the child’s uncle.

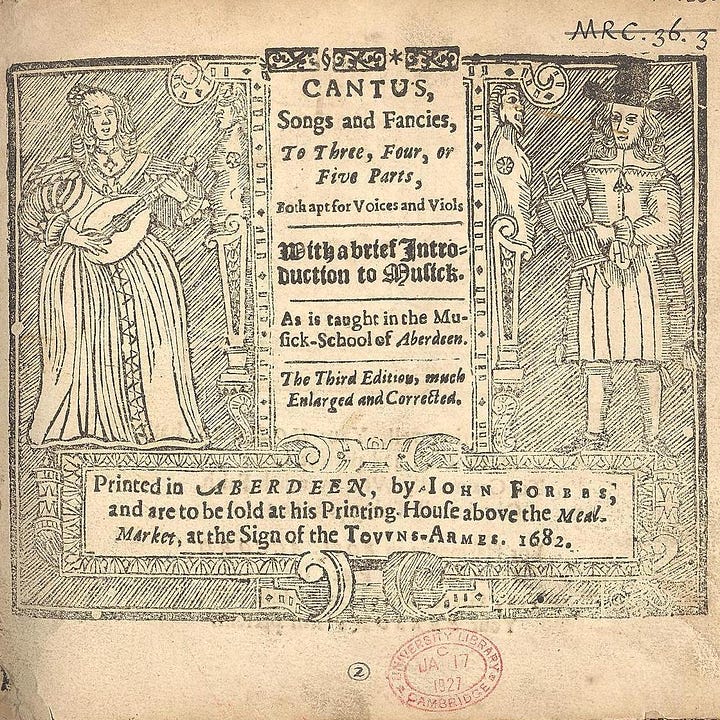

Alexander Cooper’s connections probably stemmed in part from his father, John, an Elder Burgess of Aberdeen, and his own position as Master of the Music School in Old Aberdeen. This was a post he had held since at least late 1676, since the following May, he confirmed having ‘received from John Pedder Master of the kirkwork of the said town [town Treasurer at the time] the sum of ten pounds Scots money as my salary from Martinmas May seventy-six years to Whitsunday seventy-seven years’6. Alexander’s job required him to act as Precentor (giving out the Psalms line by line, to be echoed by the congregation) and Reader and Session Clerk at St Nicholas.

By November 1681, Alexander was complaining to the Kirk Session that he needed a pay rise:

[H]is Salary as Master and reader aforesaid hath been diminished considerably besides that which was paid formerly to his predecessors in the said place (not withstanding his [expense] is now greater) and that the house belonging to him as Master and precentor aforesaid (he not having occasion to dwell therein himself) hath been untenanted and waste divers years so he hath got little or no benefit thereby since his entry.

The Session doubled his salary.

A year later, he

gave in a complaint to the Session of some private schools both in town and parish whereby the public school is very much prejudged and lest they might think he neglected his duty in the school desired the Minister and Session with the Members of the College and Magistrates of the town to appoint a visitation.

Besides music, the school was expected to teach reading, writing and arithmetic. The officials visited the next month and approved of what they saw.

Two years later, in November 1684, Alexander was back again: he had ‘been lately speaking to the Bishop anent an augmentation to his salary and that his Lordship was forward for his encouragement’. Since then, he had been told that the school in Montrose had a vacancy…. The minister and Session said they would pass on the message to the masters of the College ‘seeing it mostly lay at their door’ (ibid.)

John Couper, Alexander Thomson’s maternal 4 x great-grandfather

Music Master Alexander’s father, John Couper, was an Aberdeen merchant and burgess and probably the person referred to in 1672 as ‘Johne Couper, merchand in the Spittall’ (this being the area around the former St Peter’s Hospital, technically outside the bounds of Old Aberdeen). Alexander himself became a burgess in July 1678.

In 1688, in response to what would be termed the ‘Glorious Revolution’, John Couper was appointed one of the town quartermasters and Treasurer involved in preparing the city's defence. The following year he paid out for ‘twenty stone weight of powder and three stone weight of lead’, hiring horses for transporting ‘the English horsemen’s baggage and ammunition’ from Old Meldrum to Strathbogie (bringing back to Aberdeen the apparently stranded minister John Keith in the process), and buying clothes for the town drummer7.

As a brief background, the Church in Scotland had been an Episcopalian establishment since the Restoration. The Church’s bishops had instinctively supported King James VII when they learned that William had arrived to unseat him. Then, when James fled, they declined to acknowledge William as his de jure successor (ultimately, most accepted him as his de facto one). When Bishop Rose from Edinburgh arrived in London to assure James of the Church’s loyalty and seek support against the Presbyterians, he instead found William on the throne:

William offered Rose support for the Episcopalian establishment in Scotland, along with protection from the violence of their adversaries, in return for the allegiance of the Episcopal clergy. Rose declined to pledge any such thing. Upon his return to Scotland the Episcopalian Bishops stated that loyalty could not be transferred from King James during his lifetime. These Episcopalians… would become the non-jurors8.

The to and fro of Scottish political and religious conflict over almost two decades, leading to the 1715 Rising and all that followed, is outside the scope of this article. Safe to say that Alexander’s friends and colleagues were disappearing: of those who had attended his son’s baptisms, Principal Middleton had died in 1686; John Haliburton’s father, the Bishop of Aberdeen, was deprived of his living in July 1689; George Garden, who had supported Cooper’s doubling of salary ten years before, would be ‘deprived of his charge by the Privy Council in 1692 for refusing to pray for their majesties William and Mary’9; and John Keith would die sometime around 1694.

Back to Alexander Cooper, Alexander Thomson’s maternal 3 x great-father

Either Alexander had tired of the Session or the Session had tired of him: in February 1691, they sought to replace him as Precentor and Reader but allowed him to stay on as Master if no decision had been reached by Whitsunday (the end of May that year), when he intended to take up the post of Master of the Music School in New Aberdeen, founded in 160510. In March, they proposed to replace him as Master of the Music School, appointing Robert Gellies, ‘a young man of good life and conversation and of sufficient prudence to govern a school’11 and passing an ordnance preventing future masters from keeping a ‘change house’ (which might have been a reference to an inn but possibly referred to Alexander having a house offered to them as part of their salary but in which they did not live). However, wrangling over procedural matters delayed things: Alexander stayed in post, and Gellies found another job; Alexander eventually took up the New Aberdeen position in 169212.

By November, William Cumming from Elgin had replaced Alexander as Precentor, Reader, Session Clerk, and Master. Cumming must have faced opposition because, in November 1695, he obtained an injunction on ‘all private schools within the town either by men or women [from] teaching vocal or instrumental music’, and by July 1696, had taken up a post back in Elgin.

Cummings’ successor was William Chrystie, son of an Aberdeen burgess who was himself made a burgess the following year. Alexander, now Master of the Music School in New Aberdeen, was one of the assessors for applicants to the post, as was Cumming. Chrystie may have been Alexander’s apprentice, listed in the 1696 ‘List of Pollable Persons’ as ‘William Christall’. Chrystie asked for Cumming’s injunction to be repeated and to stop music teachers from ‘writing within the town in prejudice of the said Mr William Crystie’ on pain of censure and punishment by the magistrates. By 1705 his salary as Master of the Music School had more than doubled from Alexander’s to £26 13s 6d every half-year13, and he now received fees from baptisms, marriages, and burials. He remained in post until 1731.

Alexander’s unnamed first wife must have died not later than 1705 because the next year, he married Margaret, ‘lawful daughter to deceast Mr Alexander Robertson, Town Clerk’. This was normal when children from a first marriage were still young (Christian, the youngest, cannot have been more than ten), but he then went on to father six more children. Two were sons named Alexander, the first presumably dying young, the second born in 1715. However, his son Alexander from his first marriage was still alive, not listed as dying in 1750. This is highly unusual: perhaps there was some break between father and son (perhaps a religious one?) that effectively led to the latter being disowned.

In his second marriage, Alexander was still referred to as ‘Master of the Musick School’ and remained so, being referred to as such when tenements owned by him in the ‘Green Quarter’ (which included the south side of the Netherkirkgate) were assessed at £160 0s 0d in 171214 and also when in February 1720 his servant, George Wright, witnessed a document to fund ‘an Episcopall Meeting House’ in the city.

Alexander’s own beliefs were aligned with those of his servant. Having been refused a lease of Trinity Church by local magistrates, the Episcopalians erected their own building, St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel, and in December 1720, four months after it began services, Alexander witnessed the baptism of the son of ‘Andrew Lesly, perriwig maker’ (The opening date of the Chapel is always given as 1721, but the first baptism occurred on 14 August 1720).

Alexander died in July 1722. George, the youngest son from his first marriage, was his executor. Much of his inventory is taken up with claiming back salary owed as Master of the Music School.

Family members continued in the Episcopalian tradition and were especially evident in son George, who became a well-known Aberdeen goldsmith and silversmith.

George Cooper, goldsmith and silversmith

Born in 1689, he established his reputation in the 1730s and 1740s, principally working in silver, with an output ranging from cutlery to salvers and tea services now held in collections in Aberdeen and Edinburgh. Between 1732 and 1757, he witnessed at least fourteen baptisms, all in St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel.

His sister Christian married Captain William Baxter, shipmaster and later Bailie. Five of their seven known children born between 1732 and 1741 were baptised at St Paul’s. There was also merchant John Mair, married to Margaret Cooper; six of their nine known children were baptised at the Chapel between 1742 and 1751. Margaret was probably a grandchild of Alexander.

George remained involved in Church affairs: in March 1749, he was one of several Aberdeen businessmen collecting subscriptions to support the printing of An enquiry into the truth and certainty of the Mosaic deluge by the late Patrick Cockburn, a former minister of the Chapel, to be printed to benefit his widow15. It was published the following year. He also became Treasurer for the Chapel, in 1758 promoting the sale of ‘That House in the Gallowgate… over the gate of St Paul’s chapel’16.

George died in Aberdeen on 14 February 1765, ‘late an eminent goldsmith in this place’ as reported in his death notice17. His younger sister Isabel was his executrix, and his estate included an outstanding bond for ‘eight hundred pounds sterling’ from Charles, Earl of Aboyne, still outstanding at her death in 1769 (equivalent to £115,000 today).

Christian, the youngest sister, was Isabel’s executrix. She died in 1786 and is buried and commemorated with her husband and husband’s family in Aberdeen Cathedral. By then, George Byron had already left the private school where Elizabeth Cooper had known him, while her brother John was with ten others, studying with John Brown in the Burgher Divinity Hall in Haddington18 for a ministry that towards the close of the century would take him to the rapidly expanding Stirlingshire village of Balfron.

JEH Thomson, Memoir of George Thomson, Edinburgh, 1881

WG Rowntree Bodie, ‘St Paul's Chapel, Aberdeen: its history and architecture’ in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 1977

Byron’s reputed childhood behaviour is recorded in The Annals of Banff, 1891

GT Bisset-Smith, Vital registration: a manual of the law and practice concerning the registration of births, deaths and marriages, Edinburgh, 1902

Samuel A. Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland, 1846

AM Munro (Ed.), ‘Extracts from Session Accounts’ in Records of Old Aberdeen, 1498-1903, Vol. II, Aberdeen, 1909, spelling adjusted

AM Munro, op. cit., Vol. I

K German, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire and Jacobitism in the North-East of Scotland, 1688-1750, Aberdeen PhD thesis, 2001

AM Munro, op. cit., Vol. II

CS Terry. ‘The music school of Old Machar’ in The Miscellany of the Third Spalding Club 2, Aberdeen, 1940

AM Munro, op. cit., Vol. I

Some details on Alexander’s life here and later are taken from GJ Munro, Scottish Church Music and Musicians 1500-1700, Vol. 1, Glasgow, 1999

AM Munro, op. cit., Vol. I

Aberdeen City Stent Roll, 1712

Aberdeen Press and Journal, 7 Mar 1749

Aberdeen Press and Journal, 3 Jan 1758

Aberdeen Press and Journal, 18 Feb 1765

P Landreth, The United Presbyterian Divinity Hall, Edinburgh, 1876