By the time it closed on 15 October 1851, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in Hyde Park, London, had attracted around six million visitors, including 25,000 season ticket holders.

‘It had a number of successors: there were three within the British Isles during the next decade, all under the patronage of Prince Albert....

‘Of the immediate successor exhibitions in the British Isles, first was the Exhibition of Art-Industry held in Dublin in 1853 [with] a similar glass wood and iron structure designed by the Irish architect John Benson and paid for by William Dargan, a successful railway contractor’1.

(Smaller industrial exhibitions in Ireland had taken place even before 1851: in 1852, the Cork National Industrial Exhibition was held but, as its name implies, it focused on Irish products).

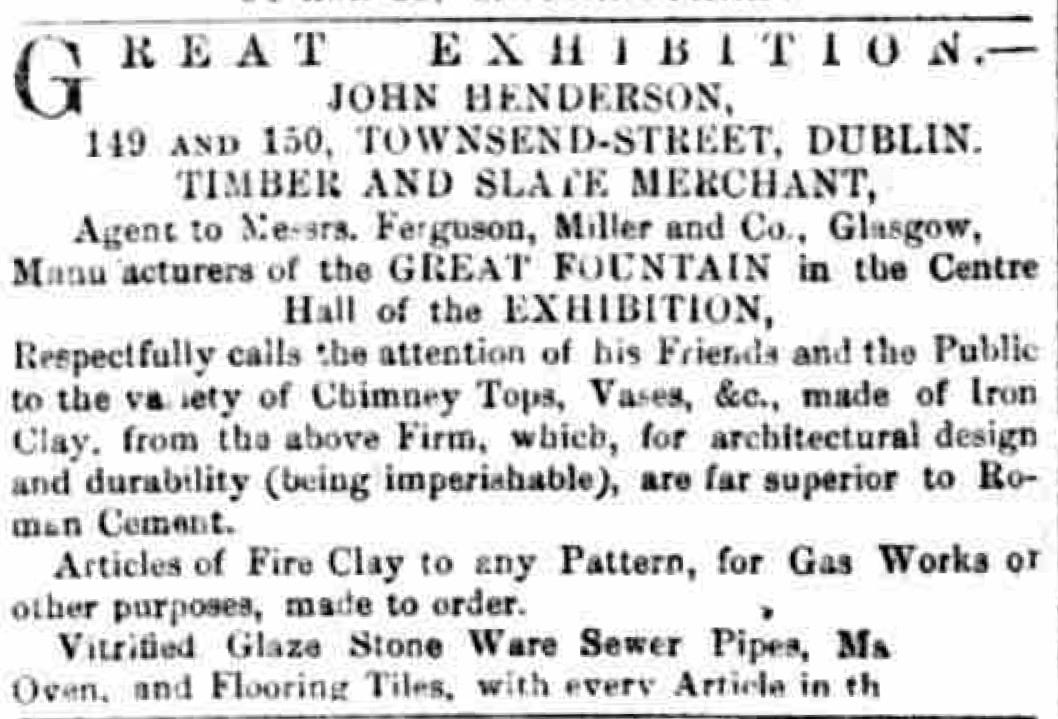

Ferguson, Miller & Co., of Heathfield near Glasgow, clearly hoped to capitalise on their success as Prize Medal winners at the Great Exhibition.

For Dublin, they again made a show of their terra cotta vases, probably including the prize-winning Nuptial Urn and the Vase of All Nations. For the former, one newspaper reported ‘the figures are drawn by Mr. George Mossman, the ornaments designed by Mr. Steele, and the vase itself by Mr. Thomson of Messrs. Baird and Thomson’, while the Vase was described as designed by George Mossman.

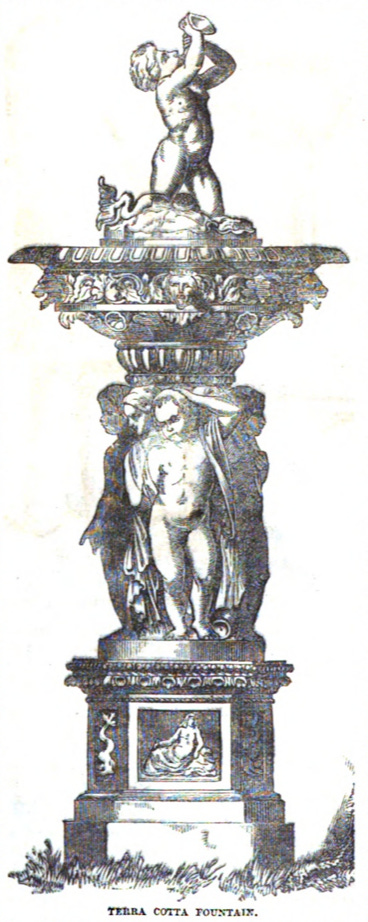

Also on show at the Dublin exhibition was a terra cotta fountain, with sculpture by Mossman, ornamentation by James Steel, but designed by Alexander Thomson. Although the Dublin exhibition opened on 12th May, the fountain was only operational six days later:

The large terra cotta fountain near Baron Marochetti's statue of the Queen2 has been completed; the scaffolding was removed yesterday evening and a trial of the fountain made, when it was found to work most admirably, throwing up a graceful jet of water to the height of about ten feet. The fountain itself is 24 feet high, and is composed of four basins - the second supported by three half-nude figures; the third by three dolphins, and the fourth by three herons, finished with the lily of the Nile, from the top of which the water is projected.... One feature in the manufacture of this fountain deserves to be particularly noticed. The second basin is six feet in diameter and we understand is the largest single piece of terra cotta that has ever been manufactured - the shrinkage on this material during the process of manufacture rendering it extremely difficult to produce an article of such dimensions. So difficult indeed was his achievement that it was not until after repeated failures of the present fountain was completed, otherwise it would have graced the great hall on the day of opening3.

In the Alexander Thomson Society’s Journal, Scott Abercrombie considered the fountain had also been displayed in Hyde Park. However, given its dimensions, it is hard to think it would not have been noticed in reports at the time, even among so many other exhibits. Nor are there any images of it in situ. In fact, the only mention of a terra cotta fountain at the 1851 Exhibition is one by a Mrs Marsh of Berlin (below), commented on as ‘not a very conspicuous object in the foreign nave [but] esteemed for its beauty of form and exquisite modelling’4.

In fact, there appear to be no press mentions of fountains in terra cotta prior to the 1851 Exhibition, but many examples afterwards. Perhaps, therefore, Ferguson, Miller & Co.’s fountain was an attempt by them both to build on the cachet of their 1851 medal-winning success, with the fountain inspired by the potential demonstrated by Mrs Marsh’s work, and created specifically for the 1853 Dublin event (Separately, although we know nothing of Thomson’s travels to London apart from the 1871 Conference of Architects organised by the Royal Institute of British Architects, it seems inconceivable that he or members of his family would not have travelled to the Exhibition at some point, especially given that some of his work was on display).

That the Dublin fountain was significant enough to attract attention is evidenced by its positioning and by at least one reference to it in the press (admittedly in an advertisement).

After the Dublin exhibition closed on 31 October, John Henderson offered it for sale. It was still located in the exhibition hall when it was put up for auction in December 1853, in a notice advertised as ‘Important to Noblemen, Gentlemen, and proprietors of Public Gedens, etc’. Ferguson, Miller’s ‘magnificent Warwick Vase. The largest and only one of its size in Ireland’ was also available, together with various other terra cotta items from the exhibition5.

The fountain was still in place in mid-December, when the exhibition hall reopened as a Jardin d’Hiver:

The large fountain, which proved so refreshing the dog days is still, but the music of its waters has been properly discontinued6.

Marochetti’s equestrian statue was also still in place.

The Jardin d’Hiver was presumably an attempt by William Dargan, who had single-handedly funded the 1863 exhibition, to recoup his losses (although popular, the exhibition lost £20,000, and this with other failed investments in hotels eventually led to his bankruptcy).

By the end of December, an anonymous nature, A Versified Description of the Great Industrial Exhibition, had appeared, stating

There’s a thing call’d a fountain, where wather is mountin’

Like a shower of rain, upside down.

The fountain was still in place in March 1854, but what happened afterwards is unknown.

As early as 1860, William D Henderson & Sons, the ‘agent for Belfast’, were advertising terra cotta items produced by the Garnkirk Fire-Clay Company in Dublin, including fountains, although most of what was being offered was more prosaic, in the form of chimney-cans, fire bricks and sewerage pipes7. John Henderson of Dublin was presumably a relative.

It is possible that the fountain was re-erected at the Belfast and North of Ireland Workmen’s Exhibition in 1870, when it was reported:

Messrs W.D. Henderson & Sons, Insurance Buildings, Victoria Street, put up in the centre of the yard leading from the machinery department a terracotta fountain which, during the Exhibition, has been in full play. Mr Henderson erected the fountain at his own expense for the ornamentation of the ground8.

Twenty years later, however, at least two versions had been constructed, although by this time Ferguson, Miller & Co. had been taken over by the Garnkirk Fireclay Company.

Dublin, Ireland

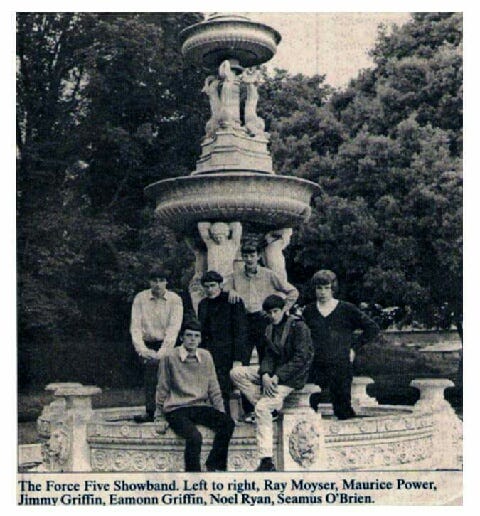

Visitors to what is now the Clayton Hotel in Ballsbridge, Dublin (above), can see a complete version of the Ferguson Miller fountain in the grounds. The building, forwhich construction began in May 1880, opened in 1882 as the Masonic Female Orphan School of Ireland. It accommodated 80 girls, replacing previous housing for 36 in the city. The fountain was presumably constructed at this time. It appears complete, save for the Lily of the Nile.

Waterford, Ireland

The Buildings of Ireland online entry on Waterford Park states that the Ferguson Miller fountain was constructed in 1883, twenty years after the Dublin exhibition. The park, however, already existed in the 1860s, displaying a pair of Russian trophy guns from the Crimea, since it was being developed later in that decade, when the Waterford News reported the planting of ‘76 serviceable trees and 200 laurels, which are growing very well [as well as] portable railings recently purchased to save the paths’. The cannons were later relocated again, with the fountain replacing them.

The park is referred to as the ‘People’s Park’ on Ordnance Survey maps of the 19th century. The fountain was reportedly vandalised in 1977, again in 1982, and ultimately dismantled in 1990, with the site now occupied by a new water feature. After the second round of vandalism, one of the atlantes was resited in 1984 on its own in a fountain at the junction of Waterside and Catherine Street in Waterford before being taken down and put into storage. In 2021, the statue emerged as a garden ornament in the Granary Café in Waterford.

Launceston, Tasmania

Launceston City Park contains the oldest known version of the fountain, ordered by then Launceston Mayor Henry Dowling in 1857 and installed for the Launceston Horticultural Society’s 1861 fete. The Society established horticultural gardens in the 1820s and handed over the grounds to the city council in 1863, and was known for many years as the ‘People’s Park’. It was also a feature of the Tasmanian Exhibition of 1891-92. It is believed to be the second-oldest extant public fountain in Australia, after that in Launceston’s Prince’s Square, which was originally set up in 1855 for the Paris Industrial Exhibition.

At its opening on 16 November 1861, the press reported:

The opening of the fountain lately erected on the walk leading from the eastern wing and immediately opposite the large conservatory, was one of the prominent events connected with the fete. The fountain is very chaste in design, and is a great addition to the attraction of the gardens. A jet of water rises in the air from the flower of an Ethiopian lily, and flowing down its expanded leaves, falls into the upper bason which is supported by three cranes. Below the pedestal on which these birds stand is the middle cup borne up by three dolphins, out of whose heads spout forth eight silvery streams which fall into the lower bason, and the water thus collected gushes out of the mouths of six lions into shells, placed immediately under the same number of elegantly shaped vases. On the base of the fountain is the following inscription - “Presented to the Town of Launceston by the Mayor and Alderman, 1861.” The outer portion of the basons and the pedestal are embellished with designs in bas relief. The vases were filled yesterday evening with blooming plants, and the fountain was enclosed in a kind of high open bower formed of pillars of evergreens hung with festoons of colored lamps, half em-bosomed in flowers and evergreens, and surmounted by oval jets of gas, whose rays falling on the sparkling, dancing water, produced a very pretty and dazzling effect9.

The fountain (below) had arrived in Launceston some months earlier, since it was reported the previous August that it had ‘for a long time… been lying in the yard of the Waterworks’ Department’10.

The park also contains an 1887 Golden Jubilee fountain from the Saracen Foundry in Glasgow (raising the money to pay for it meant that it was only finally opened to commemorate the 1897 Diamond Jubilee).

Over the years, the fountain had suffered damage, with the Nile Lily is missing, the dolphin tails broken away, and the centre bowl replaced with a fibreglass copy. A YouTube video of the 2022 repair of the fountain can be seen here.

Wellington, New Zealand

In New Zealand, a pair of domestic versions of the fountain can be found.

The site of Inverlochy House (originally ‘Inverlochie’) was purchased from New Zealand architect Thomas Turnbull, who may also have designed the house.

‘The house was built for the Macdonald family between 1877 and 1878 using mainly local timbers, but many of the original fittings such as the mosaic tiles in the hall, the ornate carved fireplaces and the two lion fountains at the front of the building were imported from Great Britain and Europe.’

Thomas Macdonald, born in Boulogne, France in 1847, was educated in Dundee and later in Adelaide, Australia. In Adelaide, he met and then married Frances Rossiter in 1870. They moved to Wellington in July 1871. Thomas worked first as an accountant before establishing T. Kennedy MacDonald and Co., which grew to include land, estate, share-broking, auctioneering and commission agencies. He also founded or promoted early tram and rail networks, and the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts.

It is possible that the house was planned for Thomas and Frances and their three young sons, but all the latter died during a scarlet fever epidemic in 1876. The Macdonalds later adopted one of Frances’ nieces.

The moulds for the fountains on each side of the entrance were likely imported into New Zealand by George Boyd, probably from the Garnkirk Fireclay Company which had taken over Ferguson, Miller some fifteen years earlier (Purchased moulds would seem more likely than importing actual terra cotta pieces, especially since the design of the fountains varies from the original: as built, they comprise a decorated basin and lions supporting a column with cranes supporting an upper basin.

The house was converted into apartments in the early twentieth century. Threatened with demolition in the late 1970s, a community-led campaign resulted in the developers offering it as an arts venue. The New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts took over and restored it between 1981 and 1986, but it now operates independently as the Inverlochy Art School. Today, both fountains are used as planters: the water supply to one was cut off after a child reportedly drowned in it in the early 1900s.

Scotland

In Scotland, the only known version of at least part of the fountain is the pelican support (above) surmounted by what is probably a Garnkirk bowl sold at auction by Lyon & Turnbull (see the post Can you buy Thomson?). Whether it remains in the country is unknown.

H Hobhouse, ‘The Legacy of the Great Exhibition’ in Royal Society of Arts Journal, Vol. 143, No. 5459, May 1995

Now sited in George Square, Glasgow

Freeman’s Journal, 19 May 1863

The Illustrated Exhibitor, 1851

Dublin Evening Mail, 28 Nov 1853

St James's Chronicle, 17 Dec 1853

The Dublin Builder, 2 Jul 1860

Northern Whig, 20 May 1870

Launceston Examiner, 23 Nov 1861

Launceston Examiner, 20 Aug 1861

Fascinating , as ever, as you explore these overgrown byways into foreign lands. I'm sure my book on the Great Exhibition (Crystal Palace, Phaidon, 1994) wouldn't help you, but you might enjoy it on your travels.