The Ure family and the Stockwell Street tenement

Part One, taking us from Bridgegate to the Gorbals

The Ure family of Glasgow bakers

In the late 1820s, John Ure was a baker at 159 Bridgegate (or Bridgegate Street, as it was sometimes named) in Glasgow. Initially from Dunipace, Stirlingshire, he seems to have moved to Glasgow a decade before, setting up business as a baker and marrying a cousin, Jean Ure, there in 1818. Her family had settled in Glasgow some years before: her great-grandfather, George Ure, was enrolled in the Incorporation of Bakers of Glasgow in 1750; George’s son and grandson followed. George’s father-in-law, William Weir, another baker, was the first it seems in his family to become one, being enrolled in the Incorporation of Bakers in 1721. John Ure himself enrolled in January 1818, less than a fortnight after his marriage, by virtue of his marital connection.

There seems to have been a close connection between anyone with the surname Ure and the baking industry. In the first 1790 Glasgow Directory, James and John Ure, the former in Stockwell, the latter in Bridgegate, were listed as bakers. They may have been uncle and nephew: in the 1799 Directory, both were listed in Bridgegate, but with James having moved in, John then moved out a short distance to 60 Stockwell Street.

By 1810, Alexander, a pastry-baker, was at 10 Hutcheson Street; George, a baker at 64 High Street; John at 60 Stockwell Street; and James at 105 Bridgegate. They may all have been related.

In early 1811, James Ure died from consumption, aged 60, and his widow must have continued the business. Later that year, the Directory entry began referring to ‘Mrs James Ure, baker, Bridgegate’.

John Ure, Jean Ure’s grandfather, died on 24 November 1820 of a ‘stomach complaint’ at age 66. His son William, Jean’s father, had died before 1819 when her grandfather drew up his will. Her grandfather had remarried in 1811 after the death of his first wife, having four more children by her. There was much to be concerned about at his death: his will runs to 21 pages and cites half a dozen properties in Stockwell Street, High Street, 18 steadings ‘part of the lands of Stirlingfold and Wellcroft, originally feued by the Govan Coal Company from the Preceptor and Patrons of Hutchesons' Hospital’, more land feued from James Laurie (of Laurieston fame), and even more at Crossmyloof.

Between 1805 and 1810, James Ure is listed at 105 Bridgegate in the Glasgow Directory, and John Ure, junior, baker, at 80 Bridgegate from 1820 to 1824. In the 1825 Directory, however, the street numbers changed for Alexander the pastry-baker in Hutcheson Street, George the baker in High Street, and John, junior, in Bridgegate. This was probably the result of Glasgow’s reorganisation of its street numbering. The two numbering changes between 1805 and 1825 may not, in fact, have represented any actual relocation of the bakery business, of course. From 1825, however, the Bridgegate bakery was at No. 159.

Park Place

Mason and builder Matthew (sometimes ‘Mathew’) Park was born in Glasgow in 1767. He was the son of Patrick Park, who had moved from Carmunnock in Lanarkshire to Glasgow sometime earlier, where, according to the Dictionary of National Biography, his family were farmers, to work as a mason. In 1806, he married Katharine Lang; together, they would have a reported six children (birth and baptismal records are hard to find). In the 1810 Glasgow Directory he was listed as ‘Matthew Park, builder’ at 375 Gallowgate; five years later, he was at 9 Virginia Street. By then, he was either completing or had just finished what would be called ‘Park’s Place’ (sometimes ‘Park’s Land’, later ‘Park Place’) at the junction between Bridgegate, Stockwell Street and East Clyde Street, at the northern end of the Old (‘Stockwell’) Bridge. Given its relatively severe design, Park may have also been responsible for that. Matthew Park and his family had moved there the following year, around the same time the Ure bakery opened up in the easternmost section along Bridgegate.

Park’s Place was a prominent enough tenement of shops and flats next to the River Clyde to be specifically identified in Allan and Ferguson’s Views and Notices of Glasgow in Former Times (below). Its residents tended to be owners of businesses based elsewhere in the city, including calico printers and wire warehousemen, but licensed premises were first opened there in 1819.

Matthew Park did not live there long, however. In July 1820, he died of ‘Decline’. At his death, he left £1,249 14s 5d (equivalent to £99,000 today), including a debt of 12s from ‘John Ure, baker’, possibly as outstanding rent, but half of which was due from Alexander and Janet Park for loans made eight years previously, probably his relatives. His property appears to have consisted of Park Place and, south of the Clyde, land off Main Street in the Gorbals1.

Overall, Park Place was a substantial, if plain, property running from Bridgegate round to East Clyde Street. When the entire block was put up for sale in 1849, it was numbered 159-163 Bridgegate, 3-11 Park Place, and 159-163 East Clyde Street2. John Ure appears to have owned his bakehouse outright: when Park Place was re-advertised in late 1850, the ‘Upset price’ for Park Place was £5,700, with ‘Messrs. Ure and Sons’ shop’ separately priced at £400’3.

The frontages on either side of the Stockwell Street entrance to Bridgegate appear below in an 1880s image, ‘Stockwell Street, Bridgegate, Park Place’, by Thomas Annan. The Ure’s bakery at No. 159 Bridgegate was the farthest shop in the block on the right; the family lived at No. 7 (presumably an upstairs flat) in Park Place.

All the upper floors at Park Place were demolished in the 1960s. The ground floor remains, although much altered, especially after a 2013 incident where a police helicopter crashed into The Clutha public house (to the right of the pedimented entrance).

Matthew Park’s historical importance largely rests as the father of the sculptor Patric Park (1811–1855). Patric was apprenticed to a stone-cutter working on David Hamilton’s designs for the north front of Hamilton Palace. Supported by the Duke of Hamilton, he studied for two years in Rome under Bertel Thorvaldson (1770-1843). In Glasgow, Edinburgh and Manchester (where he moved after becoming bankrupt in 1851), he ‘became a successful and prolific portraitist in marble producing busts of artists, literary figures, politicians and the nobility’. He died from a haemorrhage after attempting to help an old man with a hamper of ice at Warrington station in Lancashire.

John Ure

By the 1840s, John’s business had flourished: in 1845 he was elected Deacon of the Incorporation of Bakers of Glasgow4, and his marriage had produced four sons and four daughters (although not all may have survived to adulthood).

In 1851, John Ure’s heirs began to invest in property development:

The heirs of the late Mr. Ure presented an application for authority to build a tenement of houses on Stockwell Street, upon a steading of ground which has recently been occupied by an ancient fabric. We are glad to hear that in this case the architects, Messrs. Thomson & Baird, have shown commendable regard for this time-honoured locality by making their designs in keeping with the character of the street. The new building, which will be four stories high, is to be of the urban manor-house style, with corbelled chimney stalks, pointed gables, and tympany windows. The public will be pleased to see the hand of improvement at work in this old street, which formed for centuries the principal means of access to the south bank of the river over the venerable Stockwell Bridge…5

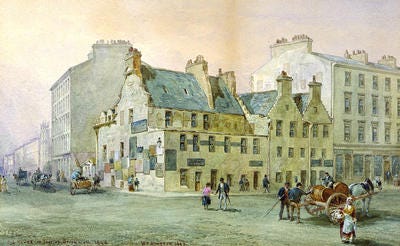

There are few images of Stockwell Street from the first half of the 19th century, so it is difficult to discern ‘the character of the street’ referred to. However, buildings that do suggest the character of the street, two-storey buildings with pitched roofs rather than three- and four-storey tenement blocks, are the former Waterport Customs House at the corner of Stockwell Street and Great Clyde Street, Garrick’s Temperance Hotel, and here.

This watercolour by William Simpson (1823-1899) was based on a sketch he had completed some fifty years before. It shows what were called the Waterport Buildings, initially where an arch had been erected to collect tolls on produce coming into Glasgow from Renfrewshire and Ayrshire, and from 1797 Glasgow’s Customs House until the opening of the purpose-built Customs House further west along Clyde Street in 1840. In 1850, two months after plans for the new Victoria Bridge were confirmed, the buildings, with land behind, were put up for sale. In 1853 they were replaced by the Victoria Building (itself now demolished and replaced by the Holiday Inn Express)6.

It is quite possible that this building was constructed and later demolished during the various phases of railway building that affected Stockwell Street later in the century, firstly with the extensive take-up of land for the lines and platforms leading into St enoch station and its adjacent goods yard, then with the widening and extension of Howard Street across Stockwell Street. It also seems clear, however, that this was not the building with its ‘five-bay pilastrade uniting the second and third floors, but supporting an arcade below the entablature’ suggested by Ronald McFadzean and repeated in the ‘List of Works’. Not only is that building, at 38 Stockwell Street (below), similar to the warehouse range at 2-16 Watson Street and Gallowgate constructed by David Thomson and Robert Turnbull for the City Improvement Trust in 1876, but in 1879 David Thomson & Turnbull were advertising ‘Three Flats at 38 Stockwell Street, To let as Warehouses or Offices’7, suggesting a direct connection.

Matthew Park’s Gorbals property

There is an indirect connection between Matthew Park and Alexander Thomson concerning the former’s Gorbals property. When put up for sale in 1848, it was described as bounded by Main Street to the east and Moncrieff Street to the west. Other properties to the south were bounded by Malta Street, while to the north, Park’s property may have extended to Kirk Street. The site was still for sale in 1849, when it was described as:

Four houses in Moncrieff Street and Kirk Street, Gorbals, with the Back Shop behind the same, and Vacant Ground on the East side thereof; as also Park’s Land, on the West side of Main Street, Gorbals, behind the land known by the name of the Ark8.

By the mid-1860s, to the southwest of Park’s property, Thomson’s block at what was then Malta Street, but later became 26-44 Norfolk Street, had been erected (Gavin Stamp’s ‘List of Works’ in Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson suggests 1860-1861), seen in the 1865 map below, where the block is bounded to the east by Moncrieff Street and to the west by Buchan Street. Park’s property appears to have been the upper half of the block to the east of Thomson’s tenement, bounded by Malta, Moncrieff, Kirk and Main Streets.

In 1874, Thomson repeated the facade of his Malta/Norfolk Street building for a new block at what was now 12-24 Norfolk Street, with splayed corners at Gorbals Cross, turning north into Main Street (later 32-70 Gorbals Street) and west into Kirk Street (later 7-21 Oxford Street). Moncrieff Street was renamed Gorbals Lane. The northern half of this would have likely covered at least part of Matthew Park’s former property at the junction between Kirk Street and Moncrieff Street (recalling the reference to ‘Four houses in Moncrieff Street and Kirk Street’ in the 1849 sale advertisement)9.

Thomson’s development does not seem to have included the properties along the east side of Moncrieff Street/Gorbals Lane (Nos 5-19), which may also have formed part of Matthew Park’s property. These remained in industrial or commercial use until at least the 1950s, as seen in the 1952 Ordnance Survey map below.

National Advertiser and Edinburgh & Glasgow Gazette, 14 Oct 1848

Glasgow Herald, 26 Oct 1849

Glasgow Herald, 9 Aug 1850

Glasgow Chronicle, 20 Sep 1845

Glasgow Courier, 11 Sep 1851

Glasgow Courier, 3 Jan 1850 and 16 Mar 1850

Glasgow Property Circular and West of Scotland Weekly Advertiser, 15 Apr 1879

Glasgow Herald, 16 Aug 1850

These two photographs from Eric Eunson, The Gorbals: An Illustrated History, Stenlake, 1996