The attractions (and risks) of country living: Thomson's Darnley Terrace

A tenement in the countryside

At the opening of the second half of the 19th century, in whichever way you travelled, within two miles of Glasgow’s city centre was open countryside. True, some were rapidly filling with villas or tenements, as well as industrial and commercial buildings. Much of the open land was being productively used, whether for grazing dairy cattle, crops or nurseries. However, especially at the city’s fringes, residents could look from their homes upon an open landscape to the hills beyond.

In the 1830s, on the south of the Clyde, as far as James Knox’s 1837 map of the basin of the Clyde, Shawlands consisted of not much more than a farmhouse in its own grounds; to the north-east (and in neighbouring Lanarkshire), Crossymloof was a group of buildings around a crossroads. By the time of the 1841 Census, the Barony of Eastwood, in which Shawlands was situated, had grown over the previous twenty years at a rate of 1,100 people a decade to 7,965, of which The nearest community of any size to the south-east was the burgh of Pollokshaws, where 4,627 lived. In all, Renfrewshire’s population was estimated at 158,075, but, at 15.9 per cent, its rate of population increase over the decade to 1841 was substantially below that of counties such as Lanarkshire (34.8 per cent or Dunbartonshire (33.3 per cent). Industry was responsible for much of their growth. Renfrewshire, however, had little of that, save along the coast in places such as Greenock and Port Glasgow (Pollokshaws’ own growth was attributed to ‘several large public works in the parish’, principally in relation to cotton: home-based handloom weaving for manufacturers in Glasgow and Paisley, spinning and dyeing. Rather, of the county’s 150,000 acres, two-thirds was used for agriculture, with the rest ‘uncultivated’ or ‘unprofitable’, according to the Second Statistical Account for Scotland. In Eastwood, only nine proprietors held land worth £50 or more, and only two of those actually lived locally. The parish had no railways or canals, and the roads ‘were oppressed with toll-dues’.

Where Renfrewshire did lead, however, was in criminality: in 1840, 653 were tried for various crimes, of whom 394 were convicted, outlawed or declared insane. This compared with 529 for Lanarkshire and 604 for Edinburghshire [Midlothian, including the capital], both with much larger populations. As the author of the Renfrewshire entry for the 1845 Second Statistical Account for Scotland wrote, ‘no other county in Scotland except the above (Lanarkshire and Edinburgh) rivals Renfrewshire in this awful sort of pre-eminence by many hundreds’.

The area around Shawlands was beginning to be populated with villas and country cottages, which offered opportunities for housebreaking In July 1851, the Shawlands cottage of Bailie Drysdale was broken into and 2 cwt of lead stolen from a bath, along with locks, window pulleys and other articles. A few days later, David McFadyen was arrested after breaking into the house of Peter Henderson, minister of Pollokshaws Free Church, which led them to discover articles from the Drysdale robbery1.

At the end of January 1852, properties in what was named Darnley Terrace, along the Kilmarnock Road in Shawlands, were being offered for entry from the following May, described as ‘Houses in the Country’2.

Darnley Terrace was typical of many locations in Glasgow’s south side, referencing Mary, Queen of Scots, reflecting the 19th-century glamourisation of her life (there might be fewer references had her troops not actually lost the 1568 Battle of Langside). Press advertisements described the properties as ‘only 30 minutes’ walk from Glasgow Bridge… yet completely in the Country’, affording ‘every facility to parties wishing a house in the country’3, and three months later as ‘most substantially built, and all painted and papered’. The flats were being shown by William Aitken, who by late March 1852 was based at No. 2 Darnley Terrace (he was living there by the following year, but before may have only stayed during the day, since he doesn’t appear in the Glasgow Post Office Directory for June 1852).

Although there is no evidence of the architect from newspapers or other records, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson’s granddaughter, Jane Nicholson Thomson (1900-1991), the daughter of Alexander’s son John, recalled: ‘I would be shown houses which [John’s] ‘father’ had built…. [including] Darnley Terrace in Shawlands where the shopping centre now stands and where they lived before Moray Place was built.’ Jane Thomson’s recollections were not always entirely accurate: she referred to Darnley Terrace as ‘Bute Terrace’. She also said that the family lived at No. 4 (it was No. 3 in 1861 unless the family moved within the terrace after they relocated from South Apsley Place in 1857).

The land on which Darnley Terrace was being built was probably sold in late 1850 or early 1851. The terrace itself would not be finished until the first half of 1853, which offered opportunities for more housebreaking: in February 1853, planks left by tradesmen working on the property were used by thieves to gain entry to one property and cut out ‘the lead of two baths (about 4 cwt.)’. Five weeks later, they were back:

‘A window which was secured by strong shutters and a cross iron bar was forced open, first by raising the sash of the window, and then forcing the shutters off their hinges, thus rendering the iron bar useless. Having gained entrance, the thieves proceeded to strip a bath of its lining of lead, and to cut away 12 feet of 4-inch lead pipe, and 12 feet of 1 1/2-inch pipe, which they carried off. The value of the lead would exceed £5, and its weight between two and three cwt.’4

Before then, however, families were already living there: within two weeks of entry being allowed (Whitsunday, that is, late May 1852), two heavily pregnant wives had given birth to daughters, Mrs Adam Boyd and Mrs Peter Bowman5. The latter did not stay long, however: the following February, Rosa & Bowman, ‘piano-forte makers, Great Clyde Street, Glasgow’6 went bankrupt, and the Bowmans appear to have moved out, possibly to live with his family (there were at least two other Bowman makers of pianos in Glasgow).

Other children followed, including a son for William Aitken in November 1853 at No. 2. Then came marriages, and some deaths. In February 1856, a hurricane swept across southern Scotland: several lives were lost, and much damage was caused in and around Glasgow, including to Darnley Terrace (probably affecting slates and chimneys), bringing down three chimney stalks at Neale Thomson's bread factory, a short distance away at Crossmyloof, as well as the steeple of the Church of Scotland in neighbouring Strathbungo.

The tenements

As built, Darnley Terrace was a block of five, three-storey tenements on rising ground facing southeast across open fields. Each tenement appears to have contained six apartments of three or four rooms and a kitchen, and bathroom, with access to the apartments through a central portico that led up and also to a garden at the rear (the hatched area shown leading from the front to the rear of the building in the Ordnance Survey map on the right below).

As built, this three-storey block on rising ground facing open land to the southwest must have appeared striking, possibly even inordinately large, compared to the villas on either side and behind. In ‘A Story about Faith’, a somewhat mawkish religious tale purporting to be written by ‘Charles’, a Scotsman in England to his son back home, a house ‘bigger than the whole of Darnley Terrace’ is cited as an example of rapid growth7.

However large, by the April 1861 Census, all six apartments were occupied in Nos 1, 2, 3 and 5 (the numbering ran from south to north), with four apartments occupied in No. 4. Alexander Thomson and his family were living at No. 3. Next door, at No. 2, Catherine Love’s occupation was described as ‘Keeps Lodgers’. At the time, she had only one: David Thomson, an architect from Glasgow.

A year after ‘Greek’ Thomson’s death in 1875, his last partner, Robert Turnbull, took David Thomson (1831-1910) into partnership: some of the buildings that immediately followed are clearly either ‘Greek’ Thomson’s designs (the Watson Street warehouses) or based upon his approach, although both Turnbull and Thomson went in different directions within a short time. The two Thomsons’ mutual awareness has never been discussed, to be explored in a forthcoming article.

Darnley Terrace

There are no known architectural drawings of Darnley Terrace, which retained its name at least until the outbreak of the First World War, and was probably renumbered as 98-130 Kilmarnock Road to reflect Glasgow’s expansion and to incorporate terraces of housing into a more coherent system.

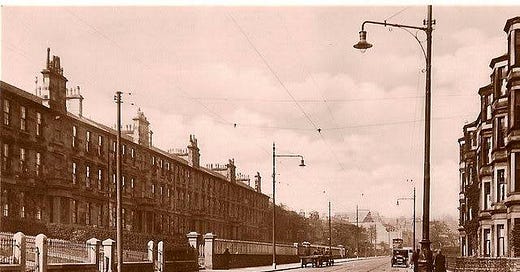

In terms of design, the image below shows this as atypical, with little visible evidence of incised carving or other regular Thomsonian details, and with the porticoes possibly intended to stop the tenement from appearing to be falling forward from the higher ground on which it was sited.

The Terrace was demolished in 1965 to be replaced by the Shawlands Arcade shopping centre, including the adjacent former Embassy Cinema and a group of three Tudoresque villas (to the left of the Terrace, and part-visible here and here). The clearest image of the terrace is from a postcard from around 1910 at the head of this article. There are also images prior to its demolition and during demolition on the Mitchell Library website8, as well as unpublished images by the architectural historian Frank Worsdall held by Historic Environment Scotland in Edinburgh.

Glasgow Herald, 7 Jul 1851

North British Daily Mail, 31 Jan 1852

Glasgow Herald, 26 Mar 1852

Glasgow Courier, 26 Feb 1853 and 5 Apr 1853

North British Daily Mail, 5 Jun 1852 and 15 Jun 1852

Glasgow Courier, 12 Feb 1853

Commonwealth (Glasgow), 4 Sep 1858

The website lists the images as c.1950, but the vehicles depicted indicate that they must all be from 1963 onwards. The image of the cinema is wrongly captioned as the ‘White Elephant’ (the Elephant Cinema, also in Shawlands, was further north-east along Kilmarnock Road)