Napoleon and the Thomson boys

How Alexander Thomson's siblings became involved in Napoleon's attempts to control Europe

John Thomson was the eldest son from his father’s first marriage (and therefore ‘Greek’ Thomson’s half-brother). John Ebenezer Honeyman Thomson (John’s nephew, although the two never met) wrote of him:

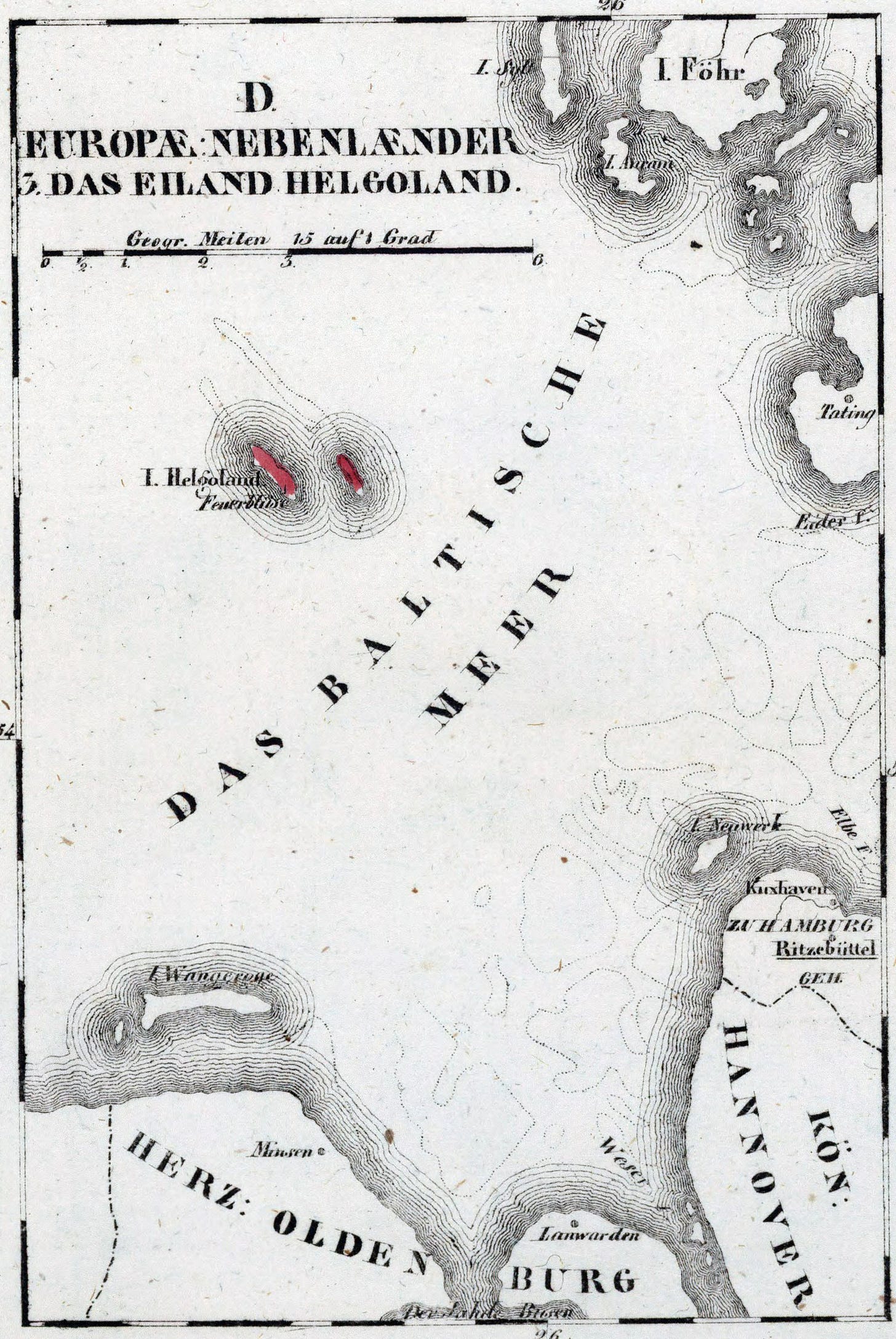

John, the eldest son, who had risen to be a junior partner in the firm of Kirkman Finlay, by whom his father was employed, died in Vienna. He had lost his health in Heligoland [mapped in 1830, above], where, as the agent of the copartnery, he was busied in contravening Napoleon’s Berlin and Milan decrees. During one of the many momentary lulls that diversified the great war, he had, with the passport of an American citizen, gone in search of health to Vienna; there war found him. While the French occupied Vienna after the battle of Wagram, he died of fever, as was first reported. Afterwards, sinister rumours reached home, that the falsity of his passport had been discovered, and the French authorities had treated him as a spy: this, however, was never confirmed. Balfron and Vienna were a long way apart in 18101.

These kinds of dramatic occurrences often appear in family histories, and to understand what was happening here (and to establish the truth about John’s death), it is necessary to know something of the long-running war between the French Emperor Napoleon and multiple European states (often including Great Britain in various coalitions), the inter-connections between military action and trade, as well as of the Thomson family’s extensive connections with the Glasgow firm of James Finlay & Co.

Great Britain and Napoleon, 1799-1807

When General Napoleon Bonaparte became First Consul of France following the November 1799 ‘Coup of 1819 Brumaire’ (above), which overthrew the Directory established after the French Revolution, it was not altogether an expected event. While he had recently returned from a failed Egyptian campaign, he was still regarded in public as a hero, perhaps in response to his final act before departing, winning a land battle at Aboukir, where his fleet had been destroyed by Nelson the year before.

In the period that followed2, France regained control of Switzerland and Holland; by early 1801, France had forced Austria to agree to an armistice, after campaigns in the Italian peninsula and various German states. While this was happening, Great Britain focused on her maritime, colonial, and commercial interests, using the profits to subsidise different Continental armies, and occasionally sending under-sized forces to campaigns too late to do any good (Minorca, for example). However, the naval blockade meant that she was able to dominate European sea trade:

When granting licenses for merchant shipping to enter the ports of France and France’s associates, they admitted neutrals only when there were not enough British ships to carry all the colonial produce of which they now controlled the sources. Moreover, the British maintained that a neutral flag did not cover an enemy’s goods and that these might be seized when destined for a port only blockaded on paper. Iron, hemp, timber, pitch, and corn (maize) were at all times to be regarded as contraband of war, and neutral ships were liable to search even when under convoy.

British naval control in the Mediterranean allowed it to capture Malta in September 1800, which Napoleon had taken en route to Egypt and subsequently offered to Tsar Paul I of Russia. In response, the Tsar placed an embargo on British ships in Russian ports and, by the end of the year, had renewed the League of Armed Neutrality with Sweden and Denmark: the Danes now occupied Hamburg, the principal port for Anglo-German trade, and the Prussians, joining a League shortly after, invaded Hannover, closing the Baltic Sea, together with German ports and rivers, to British shipping. The resulting joint loss of access to imported timber and other materials for shipbuilding, and of imported grain (which comprised around one-sixth of British consumption on average, 40 per cent at its peak) impacted British military efforts and led to a bread shortage.

Tsar Paul, however, was assassinated in March 1801, followed by a Royal Navy fleet entering the Baltic, with the Battle of Copenhagen leading to the dissolution of the League. Nevertheless, the British economy continued to suffer. Between 1800 and 1802, the Government spent some £19 million on grain imports, £5.6 million on subsidies to its allies, and £2.8 million on military expenditure (in all, over £1.8 billion at current rates)3. By the end of 1801, however, the price of wheat had more than halved from its level nine months previously.

The 1802 Treaty of Amiens between France and Great Britain, involving various trade-offs in captured lands, allowed the latter to consolidate her maritime supremacy, with an average of 20,000 ships at work between 1802 and 1815, ten times that of France. dominating colonial re-exports of coffee, tea, spices, sugar, cotton, and dyes. A year after the Treaty, the British had 34 ships of the line and 86 frigates in service; the French, at best, had access to 28 ships of the line and 25 frigates. By the end of the Napoleonic wars, the Royal Navy was three times the size of the French.

In addition to controlling sea trade, the British Government relied heavily on borrowing money to subsidise spending; even with a population twice that of her enemy, France could not. In 1813, 60 per cent of British £174 million spending was borrowed, against France’s total expenditure of £40m. When grain fell short in Great Britain, Napoleon even sold her its surplus, although for cash rather than in exchange for manufactured goods.

In spite of the Treaty, British merchants and manufacturers remained locked out of France and countries under French control. Then, in early 1803, Napoleon's official newspaper, Le Monitor Universel, claimed that Egypt might be retaken with just 6,000 troops (the army Napoleon left behind had been finally defeated in August 1801, with some 15,000 killed and the same number dead from disease). In response, the British Government decided to retain control of Malta (which was meant to become independent under the Treaty) and declared war. The French now occupied Hannover and Naples, closing Hamburg and Bremen to British trade. To raise money, Napoleon obliged both German states to pay for their French garrisons and sold off Louisiana to the United States for $11.25 million. At the time, France was receiving sizeable annual subsidies from Spain and Portugal. In 1804, Great Britain began seizing Spanish bullion ships returning from the Americas, leading to a Spanish declaration of war against her.

Seeking allies, by late 1805, Russia, Sweden and Austria had joined Great Britain in the Third Coalition, with the British offering an annual subsidy of £1.25 million for every 100,000 troops put into the field. Some German states, fearing the return of Austrian control, sided with Napoleon, now self-declared Emperor of France and Italy.

Unfortunately, the Austrians mobilised against the French before Russian troops were able to join them, enabling Napoleon's Grand Army to meet and defeat an Austrian army only one-third its size at the battle of Ulm in Bavaria (25 Sep-20 Oct 1805) and to occupy Vienna the following month (below), forcing a ‘treaty of friendship’ between France and Austria in December 1805.

In May 1806, the British Government issued an Order-in-Council establishing a naval blockade of all ports from Brest to the Elbe. It took six months for Napoleon to respond, which he did with the Berlin Decree (he had occupied the Prussian capital following their defeat at the Battle of Jena). This established what became known as the Continental System, which

forbade all correspondence or commerce with Great Britain. All British subjects found in the territory of France or its allies were to be arrested as prisoners of war and all British goods or merchandise seized. Any vessel found contravening the decree and landing in a continental port from a port of Britain or its colonies was to be treated as if it were British property and therefore liable to confiscation, along with all of its cargo4.

Other Orders-in-Council followed, banning trade between France, her allies, and the Americas, and authorising the Royal Navy to seize ships violating the blockade. The Royal Navy’s enforcement soon led to tensions with the United States. In June 1807, HMS Leopard bombarded and boarded the USS Chesapeake, looking for British navy deserters. Around the same time, US President Jackson embargoed all foreign trade, prohibiting US vessels from trading with European nations. While primarily intended to weaken the British economy, this also caused problems for American merchants.

Napoleon responded with the Milan Decree of December 1807, which extended the Continental System to every European country. It authorised French warships and privateers to capture neutral ships sailing from any port in Britain or any country occupied by British forces. And any ships that submitted to search by the Royal Navy were to be considered lawful prizes if later taken by the French.

Three months earlier, Britain had taken control of the Heligoland archipelago from Denmark (Denmark would not formally cede it until 1814). Less than thirty miles from the German coast, and comprising two small islands, only one inhabited, it became a base for British-supported attempts by merchants and traders to break the Continental System, although too exposed to be used as a naval base. Heligoland was now precisely the kind of ‘country occupied by British forces’ the Milan Decree was intended to cover.

James Finlay & Co

James Finlay & Co. were one of two firms that appeared in the first Glasgow Directory of 1783 that remain in business today (the other being the brewers J & R Tennent). James Finlay, one of four brothers from near Killearn, Stirlingshire, moved to Glasgow and established himself as an East India merchant and manufacturer. In 1778 his company gave fifty guineas in gold towards establishing a 900-strong Glasgow Highland Regiment of Volunteers to fight in the American War of Independence and reputedly played the bagpipes in a procession through the town to raise volunteers5.

James died about 1790, leaving two sons, John and Kirkman. The former, a major in the Royal Engineers and a Fellow of the Royal Society, became Secretary to the Duke of Richmond and married the daughter of George Thomson, son of Andrew Thomson of Faskine and, with his brother John, one of three partners in the Glasgow banking firm of Andrew, George and Andrew Thomson. This was a time when various wealthy families were establishing private banks, including as a means of raising capital for new business ventures. Andrew senior had previously been a partner in the Ship Bank of Glasgow. In 1785, the family established their own banking house, but this failed after eight years, attributed to the downturn in trade caused by the French Revolution. However, the family’s wealth meant that they were able to pay off their debtors. John died in 1802, leaving behind a son George (1799-1876), the noted historian of Greece and participant in the War of Greek Independence (1821-1832).

Kirkman Finlay (above) was named after John Kirkman (1741-1780), a London correspondent of James Finlay, and grandson on his mother's side of a former Governor of the Bank of England. An alderman of the City of London from 1768, he died six hours before the close in London of polling for the position of Sheriff (normally a precursor to becoming Lord Mayor), dying as Sheriff-Elect.

As head of James Finlay & Co, Kirkman sought to expand his company's involvement in cotton manufacturing, joining with members of the Buchanan family of Carston, Stirlingshire, who were already involved in the trade: their lands were adjacent to one another, and Kirkman had been trained in business in the Buchanan family’s extensive offices in Glasgow. Further, the families were already related by marriage, and Kirkman and Archibald Buchanan would marry two Struthers sisters; their family would also become involved in the business.

The growth of the Scottish cotton industry

Archibald Buchanan, one of five brothers, had been sent by the eldest as an apprentice to the inventor and entrepreneur Richard Arkwright (1732-1792), in Derbyshire; his combination of ‘power, machinery, semi-skilled labour and the new raw material of cotton to create mass-produced yarn’6 resulted in factories in Cromford and Nottingham equipped with machinery for carrying out all phases of textile manufacturing, from carding to spinning, employing some 5,000 workers.

In Scotland, the spinning of cotton yarn and then weaving it into fabric was essentially a domestic industry,

... the husband generally weaving the yarn spun by his wife, and both being assisted by their children. Up till 1773 cotton was never used alone in the formation of cloth. The yarn was not considered to be strong enough for warp, and accordingly linen yarns, procured chiefly from Ireland and Germany, were used for that portion of the fabric. The merchant supplied the linen yarn, with a certain proportion of raw cotton, to the weaver; and if the latter had not a family who could spin the cotton, he employed other persons to do so. It is stated to have been no uncommon thing for a weaver to walk three or four miles in a morning, and call on five or six spinners, before he could collect weft sufficient to serve him for the remainder of the day; and when he wished to weave a piece in a shorter time than usual, a new ribbon or a gown was necessary to quicken the exertions of the spinner.

The first cotton spinning mill in Scotland was established in 1778 in Rothesay, on the Isle of Bute, by an English company. A small affair, it was shortly after purchased by David Dale, who would become one of the most extensive cotton manufacturers in the country. Other mills followed: a three-storey mill at Dovecothall in Renfrewshire, a larger one at Johnstone, Renfrewshire, in 1782. By 1787 there were nineteen mills in Scotland, all powered by water.

In 1785, the Buchanans established a small factory on the river Teith in Stirlingshire, later known as the Deanston Works. A year later, Claud Alexander of Ballochmyle and David Dale set up a small spinning mill on the river Ayr which subsequently became the Catrine spinning, weaving, and bleaching works. In 1789, the Buchanans sold their factory and took over a mill on the Endrick Water in Stirlingshire. This had originally established by a local landowner, Robert Dunmore, employing 120 men, 90 women and 180 children between the ages of 6 and 16. Unfortunately, he had gone bankrupt in the process of building and equipping the mill, together with a new village of 105 houses and a school to accommodate his workforce, with the village using coal-gas lighting. This would become the Ballindalloch Cotton Works. One after the other, Kirkman Finlay bought out the three sites: Ballindalloch in 1793, Catrine in 1801, and Deanston in 1808.

The connection between Scotland's cotton industry and slavery cannot be ignored. By 1771, Glasgow was importing almost 60,000 lbs of cotton annually, almost half of it from Jamaica, but the Finlays would also import from the southern United States, exported via New Orleans. Between 1790 and 1810, British cotton imports would more than quadruple from 31.4 million lbs to 132.5 million lbs, and by a factor of ten to 1.346 million lbs in 1860.

As a result, Kirkman Finlay would go on to become both ‘the leading importer of raw cotton and exporter of cotton yarn’, as Britain's cotton exports also grew, by ten times, from 844,000 lbs in 1790 to 8.8 million lbs twenty years later, and by almost thirty times again by 1860.

Much of this was down to rapid industrial improvements in the last years of the 18th century: the flying shuttle, steam power, the mechanical spinning jenny, and the power loom. In 1795 Archibald Buchanan, now a partner in James Finlay & Co, introduced lighter spinning machinery worked for the first time by women (The Ballindalloch Works were said to have been the earliest cotton mills in Scotland with an entirely female workforce). Within a few years, Finlay’s three mills, employing 2500 people, and equipped with the best appliances for spinning, weaving, bleaching, and finishing, were leaders in their trade.

Innovation was met by protests, however, from workers concerned at the loss of what had been highly-skilled and often well-paid work: the inventor of the flying shuttle was forced to leave the country; in Blackburn, the destruction of jennies and carding engines ended cotton production for some years; the grandfather of future Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel saw his cotton-spinning machinery thrown into the river, and Arkwright's own mill at Birkacre, in Lancashire, was destroyed. Some members of the middle and upper classes sided with the protestors: if spinners and weavers were thrown out of work, whose taxes would need to rise to pay to support them?

For those who were first in the field, however, there were financial as well as physical risks: Arkwright wrote that it took him five years to see any profit from his investment, partly because local merchants at first refused to buy his products, and when they did so, they were treated as though they were imported calicoes, at twice the tax per yard of ordinary kinds of cotton. If printed with patterns, they were banned entirely. Only after Parliamentary intervention were the restrictions removed.

Even when workers were brought together en masse in factories, poor working conditions and poor pay resulted in demonstrations and riots throughout the late 18th and early 19th century, with workers’ associations formed as a precursor to trades unions, especially when market depression caused thousands to see their wages cut or were thrown out of work.

Conditions were, of course, much worse for those who grew and picked the cotton in the first place. Kirkman Finlay, like many others, ‘professed an “utter detestation of everything that savours of slavery” but was an extremely reluctant abolitionist’7, and one of many British businessmen who wanted (and eventually received) Government compensation for the loss of profit from its abolition8.

John Thomson père and Ballindalloch Cotton Works

When Kirkman Finlay took over the Ballindalloch Cotton Works in 1793, his brother-in-law Archibald Buchanan must presumably still have been manager there, since he was responsible for introducing spinning machinery capable of being worked by women two years later. Women were paid less than men. Archibald next moved to the Catrine Works, and then to Deanston, perhaps as each was purchased by James Finlay & Co. It may have been when Archibald transferred to Catrine that John Thomson senior, was offered the managerial post. He had started work there as a clerk (possibly a more senior position than suggested by his job title) at least by 1794, when his seventh child, James, was born in Balfron. JEH Thomson, in his biography of George Thomson (1819-1878), John's youngest son, writes:

John Thomson, George’s father, was book-keeper in [Ballindalloch Cotton Works].... He had been offered the management of the mill, but had refused it, because some of the members of the firm to whom it belonged were in the habit of coming out from Glasgow on Saturday, and spending Sabbath in looking over their books and talking business. Before coming to Balfron, he had been book-keeper in Carron Ironworks, and had left on account of similar conscientious scruples. After his refusal of the place of manager, the firm, still desirous of promoting him, offered him next the situation of book-keeper in their principal establishment in Glasgow; but he again refused, this time on account of the temptations to which his family might be exposed in a city9.

John Thomson would continue to work at the mill for many years, possibly up to his death in 1824, aged 66. We don’t know when John and his family first moved into Endrick Cottage on the banks of the Endrick Water and a short distance from the Works. In 1812, he signed a 19-year lease (a ‘tack’ in Scots legal language) with local landowner, Samuel Cooper of Ballindalloch, for the cottage and surrounding land, to be used for growing crops and collecting peat. Today, the cottage itself has been significantly enlarged, but with eight children born between 1782 and 1797 from John senior’s first marriage, and eleven more between 1802 and 1822 from his second, it would have been a crowded home, even allowing for some early deaths and the departure of the older children.

John Thomson, junior

John Thomson, the eldest son, joined James Finlay & Co in Glasgow, rising to become a partner. In 1807, probably shortly after the British took over Heligoland, Kirkman Finlay formed a shell company, John Thomson & Co, as part of an attempt to circumvent the Continental System. Another shell company was Struthers, Kennedy & Co, established in the newly-acquired British possession of Malta in 1809; the name was probably linked to members of Finlay’s wife’s family.

It was another John Thomson, manager of the Royal Bank in Glasgow and one of Kirkman Finlay’s many business partners, who was the source for the name of the Heligoland company. This John Thomson lived for some years at Northwoodside House in Glasgow before moving to Gogarburn outside Edinburgh. It was while he was at the Royal Bank in Glasgow that builder John Smith from Alloa was awarded the contract to construct the Royal Bank offices in Royal Exchange Square from designs by Archibald Elliott. Interestingly, John Smith was the banker’s brother-in-law (John’s son James, who was then in partnership with his father, would, within a few years, marry architect David Hamilton’s daughter Janet, and become the father of the accused murderess Madeline Smith).

Heligoland is not the warmest of environments, and various members of the Thomson family suffered and sometimes died from bronchitis or tuberculosis. We do not know whether John junior fell ill due to the weather or work, or why he journeyed across Europe to Austria rather than returning home. It is more likely that he travelled on business for the firm (hence the American passport) and became increasingly unwell as he did so. Nevertheless, family recollections and JEH Thomson, writing 70 years later, was mistaken: his final journey took place some three years after the French occupied Vienna for the second time.

When John Thomson junior’s will was executed, Kirkman Finlay himself described him as a ‘late merchant in Glasgow, and one of the partners of James Finlay and Company, merchants there’. He left £3,545, equivalent to almost £200,000 today, almost all held by the company.

Napoleon returned to Austria in May 1809, after the battle of Wagram (involving more than 300,000 troops, a costly battle for both sides) and, as a prelude to the five-day siege of Vienna, staying again at the Schönbrunn palace outside the city walls. This time he remained long enough for his mistress, Maria Walewska, to become pregnant with a future son, for him to survive an assassination attempt (the second in six months), and for him to inform his wife, Josephine de Beauharnais, of his intention to seek a divorce after 15 years of marriage (He would marry the 18-year-old princess Marie-Louise, daughter of the Austrian emperor, the following year but send Josephine regular letters expressing concern at how badly she was taking things).

The spy system

JEH Thomson was more correct when suggesting that John Thomson’s discovery might have resulted from the French being on the lookout for spies. This was a time when many countries used them, domestically and internationally: ‘Four or five persons attested of being the spies of this country, have been taken up and shot at Paris’, reported one British newspaper10, while in Hamburg, ‘M. Bourienne, the French Minister, rules everything here, and scarcely an act is done without his knowledge by the aid of spies and others’ claimed another11. At Madrid's city gates, 'spies are always placed to watch those who go out, as well as those who come in, while a new police has been established which has the power at any time in the night or day to enter the house of the inhabitants, and with or without cause to seize them and their effects.... This is by far worse than what they called the horrible inquisition, which they seem to have abolished only to introduce a new system of espionage and tyranny', reported a third12.

The British followed suit. In August 1809, John Pitt, Lord Chatham, leading a British army in what would become the failed Walcheren campaign, issued a decree that ‘Military deserters, and other persons belonging to the French army, not surrendering within three days, shall be punished as spies’13. A Barbados newspaper practised some scaremongering: ‘There is reason to suspect that a vast number of French soldiers are concealed at Flushing and throughout the Island; they are said to amount to several hundreds - some are discovered every hour’14. The Dutch were equally concerned, but probably more about Dutch nationals being enrolled as British spies: 'All persons going to Walcheren without passports from the proper Civil and Military Authority, should, on their return, be apprehended as spies, and sent ... for trial before a Court-Martial'15.

Even the London theatre was not immune: during a rowdy performance of Macbeth at Covent Garden, when Sarah Siddons, ‘the British Melpomene’ appeared on stage as Lady Macbeth, she was mistaken for the Italian actress Angelica Catalani, recently reported in a newspaper as ‘a spy in the service of Bonaparte’ and greeted by cries of ‘Off! Off! No Catalani! No Foreigners! No Spies!’16.

The French were dismissive of British spying capacity, however: when the Duke of Wellington landed in Spain, Le Moniteur Universel reported from Paris: ‘It appears, that he has neither spies nor any accurate information; which is astonishing in a country where England has so many partisans’17.

Back in Great Britain, even Kirkman Finlay would become implicated in the use of spies, acting in 1819-20 as an intermediary for Secretary of State for the Home Department, Lord Sidmouth, to pay former weaver Alexander Richmond ‘several hundred pounds’ (weaver’s wages were normally 10s or 12s a week) to implicate and inform on other weavers. Richmond’s information resulted in the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act and the trial and transportation of 19 weavers to Australia, and the execution of three more18.

The War of 1812

In late November 1812, however, when John junior was dying in Vienna, Napoleon was heading back overland from his failed invasion of Russia. Two months before, he had waited in what remained of Moscow for the Russians to offer terms; they had failed to turn up, and now Napoleon hared back to Paris. He left behind him 110,000 or so of the estimated 450,000 to 600,000 men he had taken into Russia the previous June, half of whom had died within six weeks. Sixteen months later, he would abdicate and be exiled to Elba.

For Great Britain, the failed Russia campaign had focused Napoleon’s attention elsewhere and allowed her to address the declaration of war signed by US President Madison on 1 June 1812. This was the culmination of the five-year dispute resulting from British attempts to counter the Continental System, including the Royal Navy’s continuing stopping of American merchant ships to search for Royal Navy deserters, to impress American seamen at sea into the Royal Navy, and to enforce its blockade of neutral commerce. More positively, depending on your outlook, ‘…the British promised refuge to any enslaved Black people who escaped their enslavers, raising fears among White Americans of a large-scale revolt. The final provocation was that men who escaped their bonds of slavery were welcome to join the British Corps of Colonial Marines in exchange for land after their service. As many as 4,000 people, mostly from Virginia and Maryland, escaped’19.

Two years before, Nathaniel Macon’s Bill No. 2 had been passed by Congress, offering Britain and France the option of ending their seizure of U.S. merchant ships and blockading trading by neutral countries. Napoleon had offered some concessions, but the British had not.

Six weeks after Napoleon crossed the Niemen river into Russia, the Royal Navy began blockading the American east coast. Two years later, the British would enter Washington DC, burning the White House and other Government buildings, and in the course of the war, acquiring territory in Maine and the Great Lakes region. The US would win important naval and military victories at sea, on Lake Champlain, and at Baltimore and Detroit. The Canadians would defeat a US invasion of Lower Canada, while the Americans would win the final battle of the war at New Orleans in January 1815 (inspiring The Star-Spangled Banner), both sides being unaware that a peace treaty had been signed at Ghent two weeks before.

The other Thomson sons

Two more of John Thomson’s sons would become involved with James Finlay & Co: James Thomson, the youngest son of his father's first marriage, joined the company as a clerk. We know little of him: he died unmarried in Glasgow in July 1829, probably having suffered from a recurring illness, perhaps tuberculosis (he refers to 'my last illness' in his will). He was buried in Balfron, from which his family had probably recently moved to Glasgow, leaving £1,839 (around £160,000 today), most held in trust by James Finlay & Co, together with ‘seven bales of Cambrics’ consigned for sale in Vera Cruz, Mexico, 18 months before, and worth around £300.

The last brother to be connected with the company was Ebenezer (1814-1847), the fifth son of John Thomson senior’s second marriage, but his connection was more oblique. He worked as a clerk at Wilson, James & Kay, yarn and goods agents, with East India contacts and offices in Glasgow’s Royal Exchange Court. He was an elder of the Gordon Street congregation, where his brothers Alexander and George worshipped. Married with two children, he died in Glasgow from typhus in October 1847.

What followed

Kirkman Finlay had died five years before Ebenezer, in 1842. Thirty years earlier, he had been elected Member of Parliament for Glasgow, the first citizen to do so in fifty years. He was also, at various times, Governor of the Forth and Clyde Navigation, President of the Chamber of Commerce, Lord Provost of Glasgow, and Lord Rector of Glasgow University.

Finlay’s successors were less enterprising than their late colleague: in 1844, the mill properties of Catrine, Deanston, and Ballindalloch were put up for sale, although only the last one was offered for and sold off. Within five years, the company had lost its impetus. In 1849 a new partner, James Clark, proposed that he join in partnership with John Wilson and Alexander Kay, the two partners of what was now Wilson, Kay & Co; the three would continue as commission agents, deal with the sale of the Catrine and Deanston works, and, in fact, do everything that company was doing except for its foreign business, such as purchasing cotton, but with all three entitled to a share of profits of the Bombay concern of Finlay, Scott & Co, whose connection with James Finlay & Co remains unclear. Clark became managing partner in James Finlay, and both Wilson and Kay would become partners from 1858 when both companies fully merged under the name of James Finlay & Co. By the time James Clark retired at the end of 1867, the assets of the business were over £1,000,000 (£89 million today). The partners’ capital was £359,000 (£32 million). Alexander Kay retired at the end of 1873, leaving a total of £115,000 (£9.9 million) invested in the firm.

When Ebenezer died in 1847 at the age of 33, he left £583 (around £48,000 today) to his wife; had he survived, he might well have progressed within the company and benefited from its growth.

The unsold works at Catrine and Deanston continued to be owned and operated by James Finlay & Co well into the 20th century, subsidised by the profits from the company’s investment in tea and Clan Line steamships, the former site eventually being demolished and the latter converted into a whisky distillery in the 1960s.

John Ebenezer Honeyman Thomson, ‘George Thomson: A Memoir’, Edinburgh 1881

https://www.britannica.com accessed 5 Mar 2023, from which various detailed information in this article is taken

Based on the Bank of England Inflation Calculator

https://www.napoleon-series.org/research/government/diplomatic/c_continental.html

Glasgow Mercury, 29 Jan 1778; Glasgow Herald, 17 Apr 1884

Wikipedia: Richard Arkwright

https://glasgowmuseumsslavery.co.uk/2018/08/14/slave-cotton-in-glasgow

While there are various Finlays listed as landowners or shareholders on the Legacies of British Slavery website, there does not seem to be a direct connection with Kirkman Finlay and his extended family.

JEH Thomson, op. cit.

London Courier and Evening Gazette, 19 Apr 1809

Star (London), 28 Oct 1809

General Evening Post, 11 Nov 1809

London Courier and Evening Gazette, 29 Aug 1809

Barbados Mercury and Bridge-town Gazette, 10 Oct 1809

Morning Advertiser, 23 Oct 1809

British Press, 19 Sep 1809

The News (London), 15 Oct 1809

https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/research-guides/radical-rising-1820

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/10/18/star-spangled-banner-racist-national-anthem/