Michael Angelo, but not that one

Uncovering the life of Alexander Thomson's (posthumous) father-in-law.

Introduction

You will search in vain for much information about Michael Angelo Nicholson, eldest son of architect and mathematician Peter Nicholson and posthumous father-in-law of Alexander Thomson and John Baird II. He is usually referred to only in the context of his father, such as his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. The Concise DNB allows him a separate five-line entry; Chambers’ Biographical Dictionary and the Encyclopedia Britannia omit both1. His date of birth is never mentioned, his date of death is usually a year out (the DNB has 1842, but in fact, it was 1841).

Michael Angelo’s family

Micahel Angelo was the only son and second of three children of Peter Nicholson and his first wife, Mary Perry. His elder sister, Mary Frances, was born in 1792 and christened at St James’s Piccadilly, as was Michael Angelo, born on 14 February 1795 and christened a month later, on 6 Mar 1795. A second son, George Peter Nicholson, was born on 28 August 1797 and christened in St Marylebone on 15 Sep 1797. A second sister, Agnes, was born in November 1799, according to a family handwritten note, but this seems to be an error. A Mary Nicholson was buried in St Marylebone in November 1797, possibly from complications following George’s birth). Also, by that time, the widowed Peter Nicholson was working in Glasgow; in the Glasgow Directory published in September 1799, he is listed as ‘Nicholson, P., architect, Hunter’s Close, Saltmarket’, under ‘Names omitted to be inserted in alphabetical order’. Peter’s children, all aged seven or younger, may have been fostered in London, or possibly (and less likely, given the distance to travel) with relatives in Prestonkirk, his birthplace.

Peter Nicholson stayed in Glasgow until at least 1808, marrying Jean Jamieson in Gorbals parish in 1804, and with their first child, George, born there in 1805 (the older George Peter Nicholson must therefore have died by then). Two later children, Jessie (1810-1895) and Jamieson Thomas Nicholson (1817-1870), were born in Carlisle and St Marylebone respectively.

It is probable that Michael Angelo, together with his stepmother and siblings, followed their father from Glasgow to Carlisle and then to London. He might have been taken to see the construction of his father’s Carlton Place (begun 1802), a footbridge over the Clyde (1803), Yorkhill House (1806), or superintending the construction of the Hunterian Museum at Glasgow College, which opened in 1808, or drawing up plans for the proposed Hamilton Building there. He may be less likely to have accompanied his father back to Glasgow while actually constructing the Hamilton Building, which was only approved by the College Faculty in 1810.

Early works

According to the DNB, Michael Angelo studied ‘architectural drawing at the school of P. Brown in Wells Street’. If correct, this would appear to be Peter Brown, better known as a flower painter, appointed in 1784 as botanical painter to George, Prince of Wales. According to the V&A, he painted on vellum, ‘the preferred medium for professional botanical illustrators in the 18th century, making use of its smooth surface to paint very fine detail. It also helped to give a sheen to the painting of leaves and petals’ (Although the V&A also describes his style as ‘naive and rather laboured’, twelve of his botanical studies of exotic plants were sold at Christie’s in 2020 for £52,500).

Brown was dead before 1818, when his daughter, Mrs Abraham, died in Euston Square at the early age of 40, ‘leaving an afflicted husband and ten children to mourn their irreparable loss’2.

Altrenatively, the DNB is in error and the reference is to the architectural drawing master Richard Brown, who in 1849 contributed ‘Recollections of Peter Nicholson’ to The Builder3.

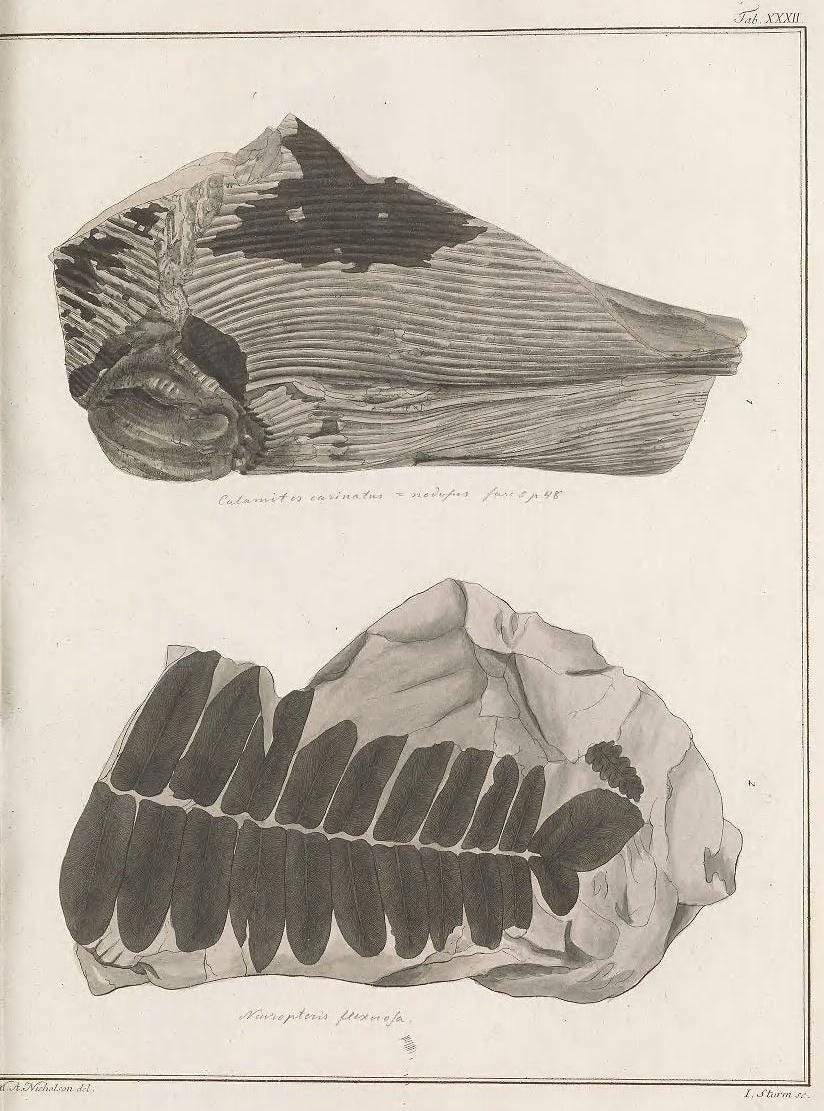

Whether tutored in drawing the natural or the constructed world, one of Michael Angelo’s early works was an illustration (below) to Grafen Kaspar Sterberg’s Versuch einer geognostisch-botanischen Darstellung der Flora der Vorwelt (An Attempt at a Geognostic-Botanical Representation of the Flora of the Prehistoric World), published in Leipzig by 1820. This kind of work does not seem to have been repeated, although it is possible that Michael Angelo contributed other illustrations to the same publication since not all are identified.

Michael Angelo had more success exhibiting at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibitions, beginning in 1812 with a ‘Design for a public bath’. At this point, his name and address was given as ‘M Nicholson, at Mr. Foulston’s, 24, St Alban’s street’. John Foulston (1772-1841) was an architect whose work drew on Egyptian and Greek models. Much of his work in Devonport remains extant (below).

In 1808, Foulston married Eliza Davies, the only daughter of the deceased David Davies of Windsor, at St James’s, Piccadilly. Two years later, he was offering for sale an ‘elegant little bijou, in the vicinity of St James’s,... furnished in a very superior manner, in the Grecian style’4, possibly in advance of a move to Plymouth, where he became the town’s chief architect for the next twenty-five years. However, the house may not have sold if it refers to the St Alban’s Street address since Foulston’s name is linked with Michael Angelo’s two years later. It thus seems more likely that Foulston, rather than Peter Brown, as reported in the DNB, was responsible for Michael Angelo’s architectural training.

In 1817, with an address at ‘12 London street, Fitzroy square’, Michael Angelo was back at the Royal Academy with A View of Belvoir Castle, seat of His Grace the Duke of Rutland, and in 1823, Perspective view of the principal front of the seat of H. Monteith, Esq. now erecting at Carstairs, adjacent to the river Clyde in Scotland. Now his address was ‘1 Euston-crescent, Euston-square’, the part of London he would stay in until his death.

In 1826, still at Euston Crescent, he exhibited Elevation of a design for a palace, on the site of the reservoir in Hyde Park, accompanied by a quotation from Bacon’s Essays:

We will therefore describe a princely Palace, making a brief model thereof. I say you cannot have a perfect Palace, unless you have two several sides, a side for the Banquet as is spoke in the book of Esther, and a side for the Household; the one for feasts and triumphs, and the other for dwelling.

His last showing at the Royal Academy came in 1828, when he exhibited Design for a bridge of suspension, proposed to be built over the river Thames, at the Horseferry, Westminster, by Capt. Samuel Brown, R.N. It was never built: just over thirty years later, Peter Barlow’s suspension bridge, Lambeth Bridge, opened in 1862 as a toll bridge to replace the horse ferry (and was itself replaced in 1932).

These were not Michael Angelo’s only works: in 1816, he drew Conway and Landscape with castle on a hill, so he must have been able to take breaks from his studies in London from time to time. Both are now held by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. They have been photographed for the first time for this article.

However, Michael Angelo may have had a painterly rival in his younger brother. In 1831, a George Nicholson lived at ‘18 Norton-street, Portland-place’ and had The dropping well at Knaresborough, Yorkshire, accepted for the Summer Exhibition. The following year, now based at ‘22 London-street, Fitzroy-square’, a few doors away from where Michael Angelo had lived some years before, he had no less than three paintings accepted: Mill, near Richmond, Yorkshire, View near Loch Katrine, West Highlands, Scotland, and Coniston Lake, Lancashire. The coincidences are not conclusive, but at least suggestive.

Publications

Peter Nicholson had been a published author since the age of 27, with his The Carpenter’s New Guide, being a complete book of lines for carpentry and joinery…, published in London in 1792 by I & J Taylor (Nicholson tended to go in for lengthy, explanatory titles to his works). Calculating Nicholson’s total output is made more complicated by the number of editions of different titles, many of them ‘augmented and improved’ or ‘corrected and enlarged’ by the author, as well as the similarity of his titles: The Carpenter’s New Guide ran to at least eight editions, between 1792 and 1826, as well as versions of the eighth edition revised and added to by others and published in Philadelphia in 1848, and in London in 1856 and 1860 by different editors. Readers could also choose from The Carpenter and Builder’s Complete Measurer of 1826, described as a sequel to The Carpenter’s New Guide, and The Carpenter and Joiner’s Assistant (1797, with six editions to 1826), and Practical Carpentry, Joinery and Cabinet-making of 1826, which itself was revised by Thomas Tredgold in 1847 and reprinted in 1849, 1852, and 1857.

What is thought to be Michael Angelo’s earliest known collaborative work with his father is his drawing of Proportional Compasses, to illustrate an 1813 article by Peter Nicholson for Rees’s Cyclopaedia, for which he also wrote articles on Architecture, Carpentry, Joinery, and others between 1802 and 1816. At 39 volumes, the Cyclopaedia was completed in 1820, with a revised American edition published in Philadelphia between 1806 and 1820. The plates were grouped separately from the texts.

The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia, whose 1813 Volume VI, Part II, covered such subjects as Christianity, Circumcision, and Clackmannanshire, included plates by father and son5. Michael Angelo provided Portions of buildings with multiple orders: Coliseum, Temple at Paestum, Whitehall, etc. for the article on Civil Architecture.

Another collaborative work with his father is his drawing of a Lighthouse (below). This dates from 1815, probably for The Architectural Dictionary, the first instalment of which appeared in June 1811, ‘Published monthly in Parts, containing six sheets of letter-press, and six plates... to be completed in 15 Parts’. The printer was John Barfield, of Wardour Street, publisher, printer and bookseller to HRH The Prince of Wales, but his involvement was destined to continue for some time to come. By November 1814, Parts 1 to 18 had been published, and the work had expanded to ‘about 24 Parts’, with Parts 1 to 24 published by April 1816 with a last Part due in ‘a few Weeks’. It was certainly completed: a full set was for sale in April 18186.

This work, however, was destined to lead father and son into legal difficulties: sometime in 1822, Barfield bought out Nicholson’s share of the work, which was described in court as ‘got up at considerable expense; it sold for 12l, the two volumes, and had cost, in preparation, more than 10,000l’. In buying the rights, Barfield obtained from Nicholson a written promise not to produce anything that would rival it or interfere with its sales. In 1823, however, Peter Nicholson’s name was linked to The New Practical Builder, a part-work printed by Thomas Kelly. Barfield took Nicholson and his publisher to court in late 1823. In November, Josiah Taylor, who with his father ran the Architectural Library in Holborn and published some of Nicholson’s other works, stated in court that this new work ‘contained many passages and plates which were the same with those of The Architectural Dictionary’.

Nicholson’s response was that he did not recall entering into the agreement, and that, to some extent, he was plagiarising both himself, using material from his 1792 Carpenter’s New Guide, and others, drawing on material ‘merely copied’ from books written long before. He and Michael Angelo had also created new material, although the son’s overall contributions were dismissed as ‘so few as to make no difference in the case’7.

As the case dragged on into July 1824, Thomas Kelly stated that he had projected the idea of The New Practical Builder back in 1821, before the covenant between Nicholson and Barfield, so should be allowed to continue publishing. Kelly said he had approached Nicholson based on the latter’s reputation. Nicholson’s counsel argued that the new work was ‘merely a book of practical instruction, and entirely different in character from The Architectural Dictionary, which was a book of reference and scientific authority’. Kelly also stated that he ‘employed Mr. Michael Angelo Nicholson to make drawings for The Practical Builder, and not one of those drawings or designs was copied from the plates of The Architectural Dictionary’. He had since ‘ceased to employ Mr. Nicholson to write any thing for The Practical Builder since he discovered the existence of the covenant’. In the end, Kelly was allowed to continue with The Practical Builder, but Peter Nicholson’s name had to be detached from it8.

Peter Nicholson’s reputation does not seem to have severely suffered as a result: Thomas Kelly continued to print his works, as did John Weale, who took over the Architectural Library after Josiah Taylor’s death.

His works

While Peter Nicholson produced some three dozen separate works in his lifetine, excluding revised editions and articles for encyclopaedias, Michael Angelo’s output was more limited.

He is likely to have produced plates for the 1814 corrected and enlarged sixth edition of his father’s The Carpenter’s New Guide, since they appear in a (probably pirated) Philadelphia edition published by Shaw & Shoemaker in 1818.

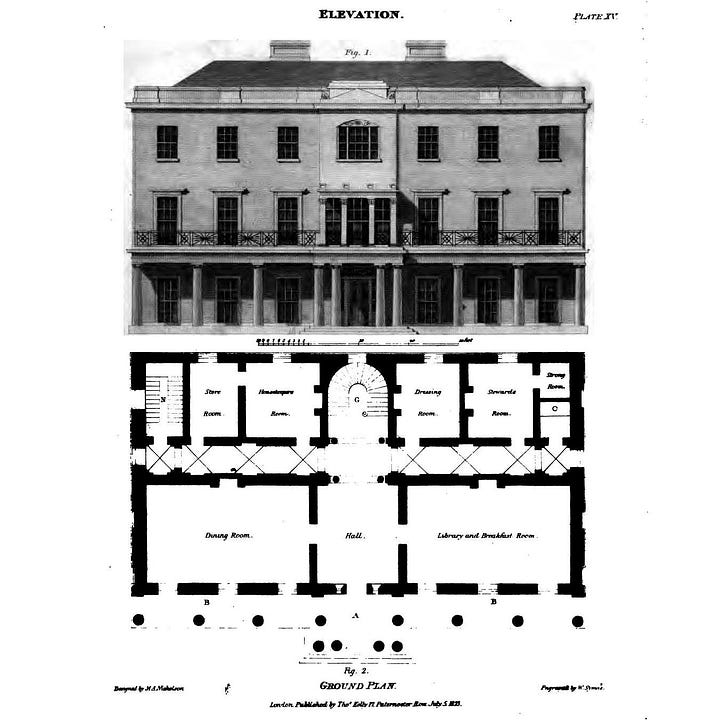

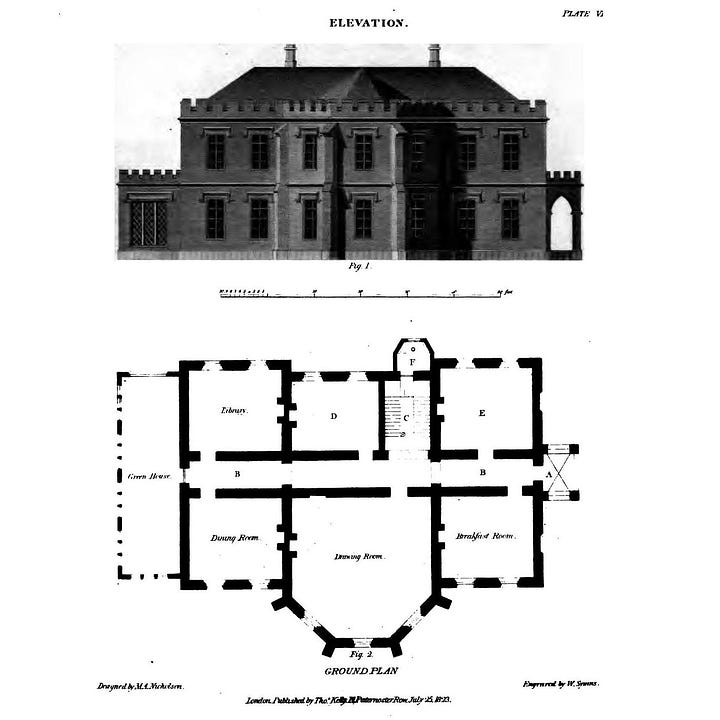

In 1823, he provided plates for The New Practical Builder, and Workman’s Companion, published in London by Thomas Kelly, but some of whose plates are dated 1822, 1823 and 1824. In 1826, he published one solo work, The Carpenter and Joiner’s Companion in the geometrical construction of working drawings ... Improved from the original principles of ... P. Nicholson (which included Joseph Derby’s portrait of his father), and a joint work with his father: The Practical Cabinet-maker, Upholsterer, and Complete Decorator, with plates by ‘Michael Angelo Nicholson, R. Elsam, W. Inwood, and other eminent architectural artists’, published in London by H Fisher & Son. Both appear to have been reprinted two years later. In 1834, came The Five Orders, geometrical and in perspective, and in 1836 The Carpenters’ and Joiners’ New Practical Work on Hand-Railing.

In 1834, Michael Angelo also claimed to be ‘Joint Assistant’ for the Architectural Dictionary of 1811-1819 and the 1824 Builder and Workman’s New Director. Since his father was still alive, the statement must be taken as valid, but whether the role involved assembling materials, contributing plates, or both, isn’t known.

The Practical Cabinet-maker, Upholsterer, and Complete Decorator appears to have been well received, although its designs must have soon appeared dated, although it may have been reprinted in 1828, when The Verulam reported, among various positive statements about the work’s technical aspects:

This is really an elegant and excellent work: no artist should be without it. It is equally interesting to the gentleman of taste and to the practical workman. It combines the principles of the most valuable science with the results of the most elegant art…. The plates are very elegant, and are coloured with great taste and skill. Handsome beds, sofas, tables, couches, chairs, etc., are exhibited…. The plates contain some beautiful Grecian and other ornaments, besides the various orders of architecture; also a representation of the easy chair in whcih the late Duke of York died9.

Truth to tell, the perspective in the various illustrations of beds (see above) appears somewhat overdone, and the illustration of a chair in which someone died seems hardly likely to generate furniture orders, however noble its expiring occupant.

In The New Practical Builder, and Workman’s Companion there appears to be a clear distinction between the plates provided by Peter Nicholson and those by Michael Angelo: the former appears to have dealt almost exclusively in mathematical models, while Michael Angelo undertook anything involving shading or illustrations of buildings.

If the ‘W. Inwood’ attribution to plates for The Practical Cabinet-maker… is correct, this would be William Inwood, (ca 1771-1843), architect with his eldest son Henry William Inwood of the St Pancras New Church, completed in 1822 and which drew heavily on Athenian models. The Royal Academy records:

When Inwood and his father were commissioned to design a new church of St. Pancras in London, Inwood spent six months from 1818 to 1819 surveying and recording the Athenian Acropolis. The two vestries of the church, in particular, proclaim the influence of the two tribunes of the Erechtheum, with its celebrated caryatids, while other parts copy the Athenian Tower of the Winds. Drawings of the church were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1819 and 1821.

In Henry William Inwood’s Erechtheion at Athens… published in 1827, most of the plates are signed as drawn by H.W. Inwood and engraved by Michael Angelo. Curiously, when William Inwood died in 1843, two years after Michael Angelo, the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1843, named him as ‘late of Euston Square’, where Michael Angelo and his family had lived, although Inwood actually died at his home in Upper Seymour Street, the other side of Euston Road from Euston Square.

Of Michael Angelo’s architectural designs we know little: in 1823, he was paid £5.13s.9d. by the Grocers’ Company for three plans for the Market House at Muff (alias Eglinton), Co. Londonderry, but his plans were never used, as pointed out by Professor James Stevens Curl in a corrective article in The Alexander Thomson Society Newsletter. The DNB claims for him ‘A plan and elevation for a house at Carstairs, Lanarkshire, … given in his father’s New Practical Builder’; in the publication there are four stand-alone houses and one castle illustrated with an elevation and floor plan, but no indication of where they might be built (The plans do not relate to Carstairs House, which was under construction at the time but was designed by Edinburgh’s William Burn). Also, there is no indication in The New Practical Builder whether these are Michael Angelo’s designs or those of his father, or both.

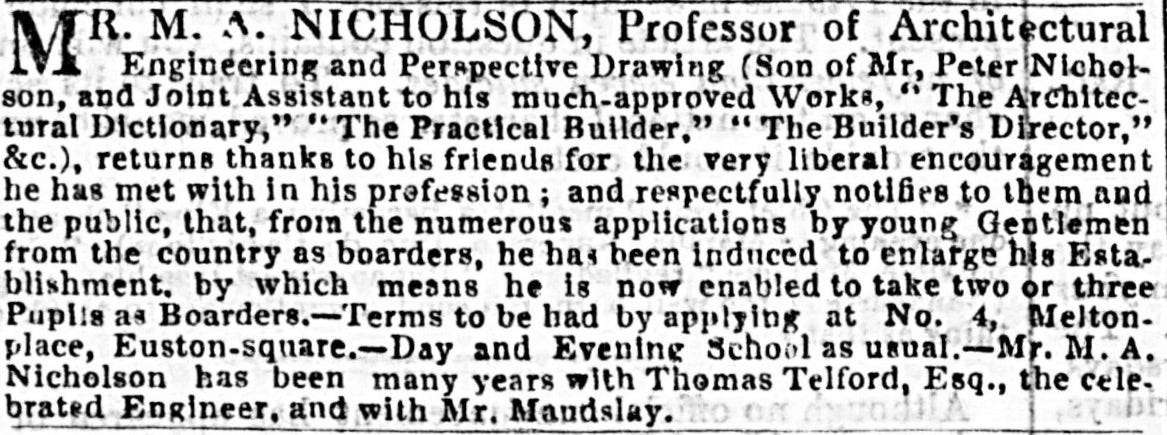

Whether as an alternative to seeking work as a practising architect, and probably recognising that mathematics, geometry and the exploration of cones, solids and spirals held less attraction for him than for his father, Michael Angelo appears to have sought employment elsewhere, probably as a draughtsman. During the 1820s he appears to have been employed by or at least connected with the engineers Thomas Telford and Maudslay.

In the case of Telford, Michael Angelo’s engagement would have been helped by his father’s previous connection with Telford in Ardrossan, Ayrshire, where, around 1806, he had undertaken work for the 12th Earl of Eglinton on the layout of the new town, with Thomas Telford engaged on the construction of the harbour. Telford had also recommended Nicholson to be appointed Cumberland’s county architect, which took Nicholson to Carlisle.

Henry Maudslay (1771-1831) was a machine tool innovator, tool and die maker, and inventor. Having worked for lockmaker Joseph Bramah, he developed the first industrially practical screw-cutting lathe in 1800, allowing standardisation of screw thread sizes for the first time. Peter Nicholson and he were likely acquainted, given their common interest in applying scientific and mathematical principles in a practical fashion. By 1810, he had established a factory on the south side of the Thames at Westminster Bridge Road in Lambeth, where he invented the first bench micrometer capable of measuring to one ten-thousandth of an inch, and began constructing marine steam engines, as well as the tunnelling machine designed by Marc Isambard Brunel to tunnel under the Thames between Wapping and Rotherhithe (now used as part of the London Overground). Michael Angelo’s work with Maudslay is unknown, but it is possible that it was in this context he, as he later claimed, improved the centrolinead invented by his father and invented the inverted trammel as an instrument for drawing ellipses.

(Instruments for drawing ellipses attracted attention and prizes: in 1813, the Society of Arts awarded a gold medal to John Farey of Westminster ‘for an Instrument for describing or drawing Ellipses of various forms and sizes’; in 1816, William Cubitt, the future civil engineer, won a silver medal for an instrument for drawing ellipses and circles without centres, and in 1818 Joseph Clement of St George’s Fields, London (and later constructor of the first working model of Charles Babbage’s difference engine) received a Gold Medal for yet another instrument that did so10. If Michael Angelo did the same, it went unrecognised, unrecorded, and unrewarded).

Michael Angelo life reflects a changing role: in the 1834 Five Orders of Architecture… he named himself ‘a professor of architecture and perspective’, in 1839 an ‘Architect’, in the 1841 Census as a ‘Drawing Master’, while in his will he was named a ‘Teacher of Architecture’. The move to teaching rather than practising came as he approached his 40s, but must have begun sometime before 1834 when he placed this advertisement (the only known reference to Messrs Telford and Maudslay)11:

Michael Angelo’s family

In April 1822 in Glasgow, Michel Angelo married Agnes Gibson, daughter of the deceased John Gibson of Partick. By 1834, they had seven children, aged ten years or less, with three more to follow, all born in London. While one child, Nancy, would die aged two in 1836, the rest would all outlive their father. It seems unlikely that Michael Angelo ever returned to Glasgow, or that he and Alexander Thomson ever met.

At some point, Michael Angelo and his family moved from Euston Crescent to a larger house in Euston Square, a block away. Nos. 1-13 Euston Square had a neighbouring terrace at Nos. 14 to 28, which together seem to have had the alternative name of Melton Place. They were a pair of southeast-facing stuccoed blocks looking onto Euston Gardens, beyond which lay Euston Street (now Euston Road). No. 4 was given as his address in 1834, No. 1 (the furthest from the camera) from 1839. After the Second World War, only Nos. 1, 9 and 10 of this block remained intact. Today, both sites, Euston Crescent and Euston Square are covered by offices and bus stands, although the gardens remain.

Michael Angelo died on 11 November 1841. The cause is unknown, but he had probably been unwell for some weeks since he made his will on 20 October that year. Probate was granted to his widow, to Robert Finlay of Greenock, a clothier and Michael Angelo’s brother-in-law (having married his wife’s sister, Marion Gibson), and Michael Angelo’s brother, Jamieson Thomas Nicholson. It is possible that the other step-brother, the possibly painterly George, had died before then.

It is not clear where he died. His will refers to ‘the house in which I dwell formerly No. 1 Euston Crescent’ (the red arrow on the map below), but that address was a block to the north, so it is possible that the family had back moved from Melton Place (the blue arrow) sometime during that year and that he had retained ownership of the Euston Crescent property while living at Euston Square.

When he died, Agnes was pregnant with their youngest child, Margaret Jamieson, born in December 1841. Sometime later, Agnes returned to Glasgow with her family. The eldest daughter Margaret died there in March 1845, the youngest, Margaret Jamieson, in May, and Agnes in December of the same year.

In 1847, the second and third eldest daughters, Jane and Jessie, married Alexander Thomson and John Baird II in a double ceremony. The year before, Michael Angelo’s eldest son, Peter Angelo, had moved to Philadelphia, where he married, practised as an architect, and died in 1902. In 1851, the next eldest daughter married John Fraser from Peterhead, bearing him three daughters, but dying less than two months after giving birth to her last child in December 1857.

The next son, Michael Angelo, became a carpenter, then joined the Merchant Navy, sailing mostly out of Liverpool on voyages to Australia and Canada, and gaining his Second Mate’s certificate. For almost a decade from 1882, he was a patient at Gartnavel Royal Asylum but eventually left, and appears to have died unmarried, possibly at Colney Hatch Asylum, in Friern Barnet, Hertfordshire12, in 1903. The next brother, John Thomas, also went to sea but was present at the battle of Banda in India in September 1858. He may well be the person admitted as a hospital patient to Colney Hatch in July 1875 who either died there or was discharged in December 1875 (the record is unclear), but nothing more is known of him.

The last sister, another Nancy, was living with Alexander Thomson’s family in 1861 at Darnley Terrace, Shawlands (the Thomsons moved to 1 Moray Place later that year). In June 1876, at West Bennan on the island of Arran, she was found dead by a well, of unknown causes. She was unmarried.

(Updated with thanks to Dr Alistair Macdonald for corrected information).

Dictionary of National Biography, London, 1885-1900; Concise Dictionary of National Biography, Part I, 2nd ed., London, 1961; Chambers’ Biographical Dictionary, Edinburgh, 1993; Encyclopedia Britannica, 15th ed., Chicago, 1974

Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 13 Dec 1818; Morning Post, 10 Dec 1818

per Dr Alistair Macdonald

Morning Chronicle, 20 Aug 1808; Morning Post, 18 Jun 1810

Caledonian Mercury, 24 Jun 1813

Hull Advertiser, 22 Jun 1811; Star, 29 Jun 1811; The Courier, 7 Nov 1814; Liverpool Mercury 19 Apr 1816; Suffolk Chronicle, 4 Apr 1818

St James’s Chronicle, 22 Nov 1823

ibid., and Morning Herald, 28 Jul 1824

The Verulam, 17 May 1828

Lancaster Gazette, 5 Jun 1813; Norfolk Chronicle, 8 Jun 1816; London Star, 28 May 1818

Morning Herald, 28 Oct 1834

per Dr Alistair Macdonald