A decade after the 1851 Great Exhibition, the 1862 event was intended to build on what had come before, but the recently concluded war in the Crimea and the ongoing American Civil War illustrated how the world had changed in just over a decade.

Located on a twenty-acre site of what is now the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, the event attracted some 6 million visitors and even turned a profit (£790), but the attitude of many newspaper reporters at least, was far less respectful compared to the 1851 exhibition. Much of this could be attributed to the largely unornamented cast iron and brick exhibition building, which had been criticised even before it opened, and especially the interior, when compared to ‘the aerial and almost supernatural lightness and freedom of Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace’. Occupying the same area as the Crystal Palace, although arranged more squarely, the way in which the 28,000 exhibitors from 36 countries were crowded together leading to ‘the unpleasant resemblance which a considerable portion of the interior thus bears to a great fancy bazaar’1.

Featured in the British section, and occupying the nave, ‘the Oxford-street of the exhibition’ were three obelisks, ‘one made of Cheesewring granite, 27 feet high; the other made of grey granite from the Ross of Mull, 35 fete high. In the mineral court there [is] also a beautiful serpentine obelisk, 15 feet high’2. Another newspaper reports an obelisk of coal, while from Australia came an obelisk 42 feet high made of wood gilt:

‘It represents the build of gold which Australia has enriched the world since 1851, and had it been the gold which it only represents it would have weighed eight hundred tons’3.

But the crowding together made appreciation of individual works more difficult:

‘It does not matter that Mr. John Bell’s model obelisk, made of granite from the Cheesewring Works, and ornamented with bronzes from the Coalbrookdale Company, is graceful and worthy of the cluster’s fame: it is out of place, and consequently ugly’4.

The fashion for obelisks

The first known obelisk in Britain was erected in the time of Queen Elizabeth as part of the works to complete Nonsuch Palace, begun by Henry VIII and unfinished at his death in 1547. The inspiration - and obelisk - came from Rome, where Lord John Lumley, son-in-law to the 12th Earl of Arundel - who was in charge of the works - had spent some time. Lumley’s first obelisk, ‘of streaked and veined Italian marble [with] his own coat of arms carved upon it’, was some 20-30 feet tall and was soon joined by other smaller ones5.

Lumley’s obelisks inspired others in gardens, on tombs, and as rooftop finials. In Scotland, obeliscal stone sundials became fashionable: the one at Castle Drummond, Perthshire, adorned with Masonic symbols, was erected in 1630, one of some seventy such sundials thought to have been erected in Scotland alone.

Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt and the many scientists, engineers, and specialists he took with him spurred renewed interest in obelisks as historical artefacts rather than mere decorative features, especially after the publication of Baron Denon’s Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt, translated into English in 1803, and his Description of Egypt, begun after he had been appointed Director of Museums (and founding the Louvre in the process). The Philae Obelisk was removed by the British Consul General Henry Salt in 1819, with the assistance of one-time theatre strongman-turned-mover of heavy objects Giovanni Belzoni. The hieroglyphs showing Cleopatra’s name aided Jean-François Champollion in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Almost two decades before Salt obtained the Philae Obelisk, a British patrol had chased off a group of French academics and troops while removing an upright obelisk in Alexandria. A half-submerged granite obelisk nearby was seen as an easier trophy. At 186 tons, it would take seventy-seven years for the obelisk to reach the Embankment in London and be installed as ‘Cleopatra’s Needle’ (the standing obelisk, its partner, would later end up in Central Park, New York).

The Egypt-inspired fashion for obelisks extended to buildings ranging from the Egyptian Hall in London to a flax mill in Leeds and Brunel’s 1836 Clifton Suspension Bridge. In London, the first public obelisk-as-monument was raised in 1833 to commemorate Robert Waithman, sometime Sheriff, then Lord Mayor of London, and MP. However, the adoption of an architectural style from such a distance raised its own concerns:

‘Gothic for Romance, Classic for Reason: that was the civilised, tolerant Georgeian view. The Victorians, less gracious but far more serious, would have none of it: Gothic for Christianity, Classic for Paganism was the war cry of the Gothic revivalists in the battle of the Styles’6.

Alexander Thomson’s personal experience of obelisks would probably have been limited: David Hamilton’s 1806 144 ft sectional sandstone obelisk in Glasgow Green commemorating Lord Nelson would probably be the one with which he was most familiar, although he would have seen the 1836 obelisk at Dunglass Rock, commemorating steamship builder Henry Bell, during journeys down the Clyde, and the one from 1872 also commemorating Bell in Helensburgh. He may have been aware of the 1854 20 ft millstone obelisk for shipbuilder William Denny in Dumbarton Cemetery and of others that proliferated in Scottish graveyards and elsewhere during the 19th century. However, the first major obelisk he likely encountered would have been as a child: James Craig’s 1788 100 ft obelisk for George Buchanan at Killearn, less than three miles from Balfron.

The death of Prince Albert

Queen Victoria did not attend the 1862 exhibition opening: she was still in mourning for the death of her husband, the Prince Consort, on 14 December 1861, at the age of 42. Shortly after, the question of how best to commemorate his life arose.

Back in 1859, architect John Bell (1811-1895) proposed an obelisk, ‘The Great Exhibition Memorial’, to commemorate the Prince’s involvement in the 1851 Exhibition. Albert liked the idea but commented that any monument should not be a thing to frighten the horses in Rotten Row.

Bell was a friend of both the Prince Consort and Henry Cole. He had exhibited both in the 1851 exhibition’s sculpture gallery and the industrial section with works by Coalbrookdale and Minton. The latter works were of Parian porcelain, resembling marble, at which Bell was both prolific and popular. The idea was talked about, but never really moved forward.

Bell persisted: a week after Albert’s funeral, he went to Henry Cole’s house and pressed the idea of a commemorative obelisk again. At 80 to 100 feet tall, it would be the largest ever constructed, using a single granite block, at an estimated cost of £50,000. Three weeks later, a committee met at Mansion House under Lord Mayor William Cubitt (contractor for Covent Garden, Fishmonger’s Hall, Euston Station and the Cubitt Town development in east London). They considered the obelisk proposal: the Queen was initially favourable, as she wrote, to the idea of “an obelisk in Hyde Park on the site of the Great Exhibition of 1851, or on some spot immediately contiguous to it”.

In the press, however, there was widespread debate: about the suitability of an obelisk as a memorial, about the viability of finding a single block of granite, about its location, and its cost. Various other ideas, including establishing a university or international scholarships, were put forward. The Earl of Dalhousie proposed a monument in Edinburgh, to be paid for by contributions from across Scotland, to which the press response was somewhat adverse:

‘We hear great diversity of opinion as to the desirableness of the provinces contributing large sums to further aggrandise the city of Edinburgh - which is already rich in monuments.’

In Aberdeen, a statue was being considered, while in Dundee the ‘Albert Free Library’ was being considered:

‘Such an institution would have a living utility not to be found in any dead piece of stone’7.

Control of the committee soon moved from Mansion House to the Palace, under the Queen’s Secretary, General Charles Grey, and the Keeper of the Privy Purse, Sir Charles Phipps. By then, the idea appeared to be of an obelisk ‘as the distinguishing characteristic of the proposed monument’ with surrounding statuary. In April 1862, the Committee reported:

‘Only one monolith of the size required seems obtainable in England, and that one appears imperfect; that the expose of cutting, removing, and erecting it involves a calculation for which they have not any data; and finally, that they are doubtful of the effect of success’8.

The Queen gave in, but not without suggesting what might happen next. She wrote from Osborne on 16 April 1862:

‘Her Majesty’s wish is to leave the Committee quite free to recommend whatever may appear to them to afford the best hope of a satisfactory result and she would nearly throw out as a suggestion whether the opinions of some of the foremost architects of the day might not be advantageously taken as to the means of combining the groups of statuary mentioned in my letter to the Lord Mayor, among which of course a statue of the Prince would be prominent, with some other design’.

Thus, two weeks before the 1862 Exhibition opened, it was clear that there would be an Albert Memorial, but it would not be Bell’s obelisk - or any obelisk. This was unfortunate for an American gentleman who called around the same time on the Lord Mayor ‘with the offer of a block of grey granite 150 feet in length and 12 feet square… now lying in America within 12 feet of the water’s edge’, to be informed that ‘the idea of a monolithic obelisk had been given up’9.

It was also unfortunate for the Scottish Granite Company of Kingston, Glasgow, which went bankrupt in 1867. Five years after the 1862 exhibition, it still retained in its Tormore Quarry ‘the great Block known as the ‘Albert Memorial Stone’, which it was at one time proposed to remove to London, and out of which might be manufactured one of the largest Pillars or Obelisks in the World’ (This appears to have been more than mere hyperbole: the company’s stock also included ‘Eight large Red Granite Columns for the new Blackfriars’ Bridge in London’). Perhaps this is the stone Bell hoped to use10.

A short while later, in line with the Queen’s suggestion, it was announced that several architects would be approached for their designs: Bell, as a sculptor, was not included.

One member of the committee, later its chairman, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, President of the Royal Academy, was the effective artistic arbiter. A range of designs were eventually submitted to the committee; those by Philip Charles Hardwick and George Gilbert Scott were passed to the Queen in February 1863 for a final decision. After lengthy deliberations and negotiations with the government over costs, Scott’s design was formally approved in April 1863. However, John Bell was not entirely left out: he was invited to make the ‘America’ corner group of the Albert Memorial. His original sketch is shown below; the much simpler actual group is here.

In fact, the first memorial erected to the Prince Consort was an obelisk. It was made of Purbeck stone and erected at Swanage, Dorset, in 1862. That monument, proposed only four weeks after Prince Albert’s death by a local builder, took its design from Waithman’s obelisk in London. The Swanage obelisk, taken down in 1971 to make way for housing, was relocated and re-erected in 2021.

Thomson and the 1862 Exhibition

We have no evidence that Thomson or the companies he worked with submitted work for inclusion in the Exhibition. Neither Ferguson, Miller nor the Garkirk Fireclay Company, both of whom exhibited in 1851, appear to have provided exhibits, nor did the Oak Foundry, while Waler McFarlane’s Saracen Foundry exhibited only ‘some rather elegant small castings’11. Indeed, among the British entries, the exhibitors were, if anything, even more heavily London-centric than in 1851. There was an architecture section, Class XXXVII, with a committee including Sydney Smirke, Matthew Digby Wyatt, George Gilbert Scott and William Tite, MP, FRS, President of the Institute of British Architects. I have not so far located any information about what might have been on show, either in the form of models or drawings.

The Exhibition’s Handbook to the Fine Art Collections by Francis Turner Palgrave covers painting, sculpture, engraving and architecture, essentially comprising a historical review of each subject and the author’s take on different works on display, often highly critical. The exhibition’s sculptural offerings come in for particular criticism: “Careful examination.. which began with a belief in the excellence of [Baron] Marochetti's work... led, gradually and surely, to a conviction of its baseness” (elsewhere, he criticises the Baron’s “empty extravagance”.

On architecture, he provides a historical overview of styles, from Greek through Roman, Romanesque and Byzantine, Gothic and Pointed Gothic, with the briefest mention of others (“Palladian.,. is still but a copy of a copied architecture - a galvanised pedantry”), and does so without identifying a single architectural work or contributor to the Exhibition. He does, however, nail his colours firmly to the mast, not just in favour of Gothic, but Gothic for eternity:

‘Gothic is simply the one style which, by the circumstances of its development, has united in itself all the best constructive and the best ornamental forms of the world’s inventions in Architecture.... Why seek impossible new forms, or repeat styles which are bastard, or lifeless, or unpractical,—whilst men of like passions and blood with ourselves have solved the problem once, perfectly, and for ever?

Palgrave’s opinions in the Handbook got him into trouble: alongside criticising Marochetti, he praised the work of a rival, sculptor Thomas Woolner. It was then pointed out in print that Palgrave and Woolmer happened to share a house. The Handbook was withdrawn.

Palgrave might have gained some little satisfaction that Marochetti, who was initially commissioned to provide the statue of Prince Albert in the Albert Memorial, had his first design rejected and died in 1867 before his second one was approved.

Thomson and the Albert Memorial

Of Thomson’s presumed design for the proposed Albert Memorial, the ‘List of Works’ in the 1999 book ‘Greek’ Thomson states:

‘This project is puzzling as Thomson was not among the nine architects invited to submit proposals for a Memorial to the Prince Consort in 1862 following the advice of Sir Charles Eastlake, PRA. However, Joseph Durham, James Fergusson and J.L. Hittorf are also known to have prepared designs’.

The ‘List of Works’ suggests that Thomson’s design was speculative. George Gilbert Scott, for example, had done the same when an obelisk was still under consideration, as he recorded later:

‘For my own personal satisfaction and pleasure, at the time when a monolithic obelisk, 150 feet high, was thought of, endeavoured to render that idea consistent with that of a christian monument. This I effected by adding to its apex, as is believed to have been done by the Egyptians, a capping of metal, that capping assuming the form of a large and magnificent cross...12’

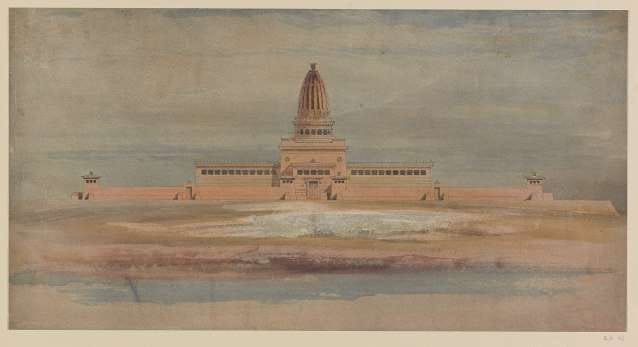

The ‘List of Works’ quotes Thomas Gildard:

'‘The design for the London Prince Albert Memorial showed the colossal bulk with the sublimity of the Egyptic tempered by the subtle proportioning and the refining graces of the Greek’.

The first question arises as to whether this is indeed Thomson’s thinking for an Albert Memorial: the ‘List of Works’ notes Ronald McFadzean recollecting ‘a drawing for a similar design but with a monumental flight of steps in the Glasgow School of Art in c.1950 which has since disappeared’. And does the design above match Gildard’s description? Would not the quasi-Assyrian dome have drawn a comment from him (it being neither Egyptian nor Greek)?

If this is Thomson, and given that an obelisk had been set aside as a design option for the Albert Memorial, is Thomson’s design purely speculative, in case those of the architects under consideration were not accepted and the work thrown open?

Thomson’s design, involving a large cruciform plinth, would require significant space, although that was available. As The Scott Dynasty website writes:

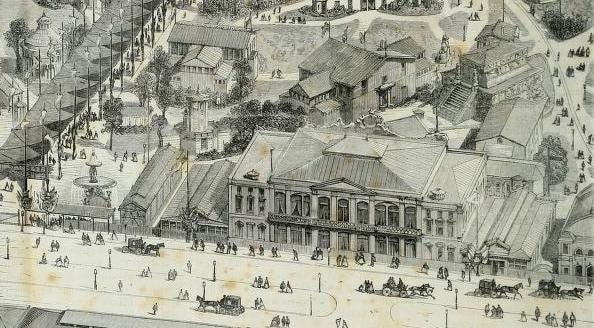

‘By this time the great rectangle of the Commissioner’s estate, between Exhibition Road and what is now Queen’s Gate, was being developed as gardens for the Royal Horticultural Society and, in March 1861, work started at the southern end of the estate on the enormous structure that was to house the 1862 International Exhibition. Captain Fowke had designed the building to be symmetrical on the centre line of the estate and it was a continuation northwards of this line to the spot in Hyde Park, where it crosses the east-west axis of the site of the Crystal Palace, that it was decided to site the Albert Memorial’.

Although never apparently submitted for consideration, Thomson appears to have been proud of it; the ‘List of Works’ quotes Henry-Russell Hitchcock as remarking on a design for the Albert Memorial being shown at the Paris International Exhibition in 1867, which may refer to the drawing above, to the one remembered by Ronald McFadzean, or another. There was little that could be deemed classical Greek on show in Paris; Egypt was much more in evidence, perhaps reflecting the connection with Napoleon, with pavilions and a temple demonstrating Egypt’s past glory. If Thomson was exhibited, it would have been in the Fine Arts section (below) of the ‘English Quarter’ (which actually included buildings from several other countries, including Egypt).

There does not appear to be any comprehensive guide to the 6,000-plus exhibits from the UK, although it is known that George Washington Wilson exhibited photographs of the Royal Exchange, Glasgow and the Soldier’s Leap, Killicrankie. English photographers also exhibited. No obelisks were evident in the English Quarter, and only one is mentioned in the L’Exposition Universelle de 1867 Illustré, issued in 60 parts and totalling almost 1,000 pages of engravings and commentary, but that was made of iron and came from Russia. Incidentally, the publication details Gilbert Scott’s Albert Memorial, although it identifies the Albert Hall as the ‘Museum of South Kensington’.

Thinking back to the 1853 Dublin Exhibition, there is a fountain, seen in the lower left corner of this part-image of the English Quarter, described as a

‘monumental fountain, whose jet of water, in the least wind, dampened all the surroundings and made unusable the benches on which the tired visitor might find a moment’s rest’.

However, this does not appear to be Thomson’s terra cotta fountain from Dublin, and there is no mention of terra cotta work in the Exposition guide.

Thomson’s obelisks

Before 1862, only one obelisk, a funerary one, is known to be by Thomson, for the sculptor William Mossman, who died in 1851. Two later ones were the Middleton (c. 1867) and Inglis monuments (c. 1868), both in Glasgow Necropolis. The Sprott monument (c. 1876) in Craigton Cemetery may be a reworking by Robert Turnbull or someone in the office of a Thomson design (Sprott died a month before Thomson). Given the fashion for obelisks, it seems unlikely that Thomson did not design any more such monuments in the fifteen years between Mossman and Middleton.

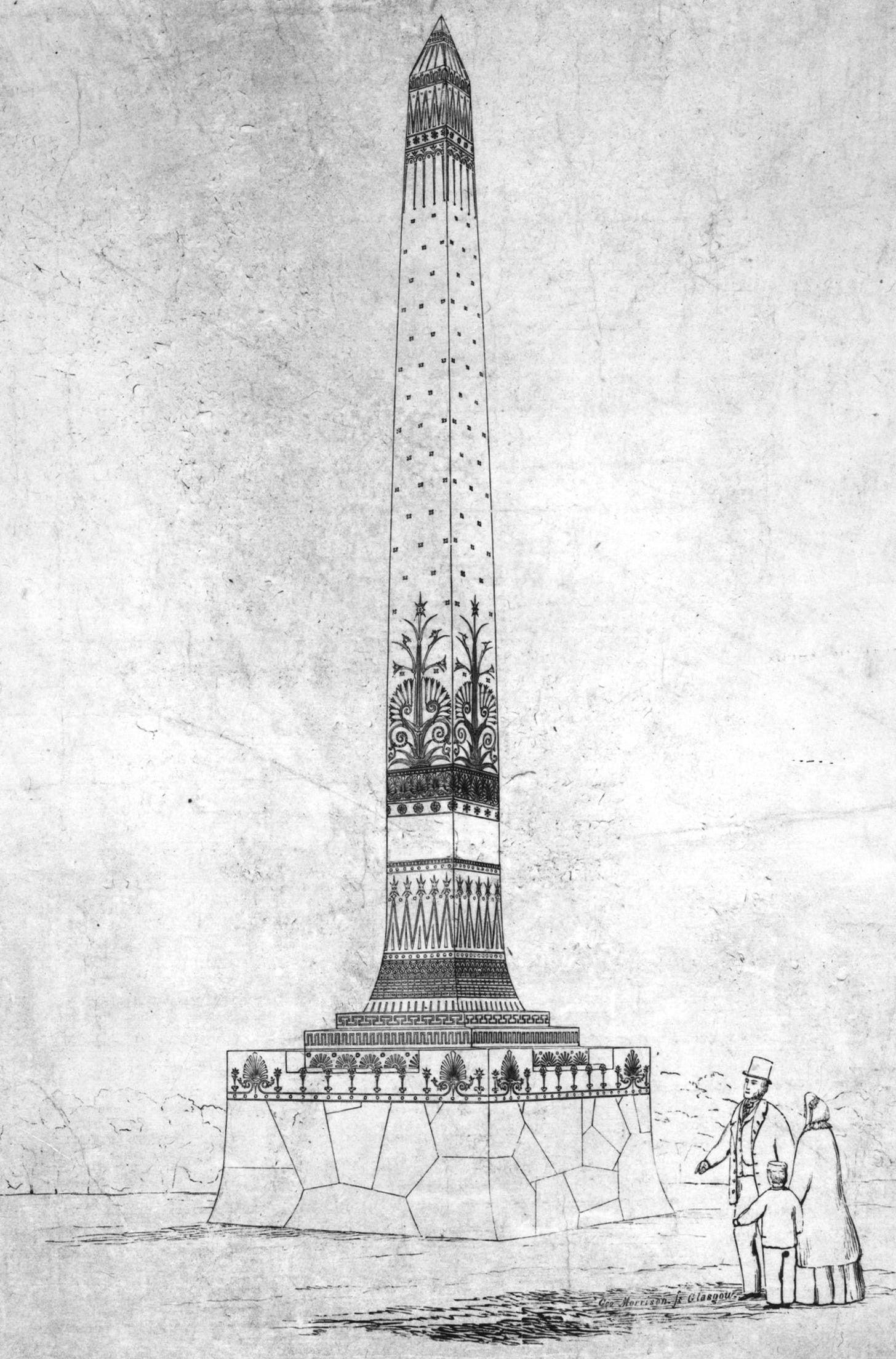

There are three drawings of obelisks in the Mitchell Library. One is the perspective drawing (above) by George Morrison (a draughtsman and engraver, d. 1909, who worked out of Buchanan Street and then Hope Street in the 1870s). All the obelisks are monumental in scale, so clearly not simply for a tomb, and they are all slightly different. If Morrison’s perspective is considered accurate, and taking the adult male figure as being 6 feet tall (without the hat), the obelisk would be between 30 and 40 feet in height.

Interestingly, all employ cyclopean masonry for the base, only used by Thomson previously for the 1854 Mossman workshop at the corner of Cathedral Street and North Frederick Street, and the 1856 Caledonia Road Church, and then, in the late 1860s, for the Beattie monument in Glasgow Necropolis (c. 1867), the tomb for John McIntyre’s son in Cathcart (1867, and later for other members of the family)13.

Greenock Telegraph, 3 May 1862

Bristol Times and Mirror, 3 May 1862

Dover Telegraph and Cinque Ports General Advertiser, 3 May 1862

London Evening Standard, 6 May 1862

R Barnes, The Obelisk, Kirkstead, 2004, from which much of this section is taken.

J Gloag, Victorian Taste: Some Social Aspects of Architecture and Industrial Design, 1820-1900, London, 1962

Dundee Advertiser, 1 May 1862, also above

Bradford Observer, 1 May 1862

Wiltshire Independent, 1 May 1862

Glasgow Herald, 31 Jul 1867

The Record of the International Exhibition, 1862, Glasgow, 1862

G Gilbert Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, London, 1879

Thanks to John McKean for identifying the Caledonia Road Church.