Introduction

Even with the substantial number of records available, the precise order in which plans were drawn up, architects consulted, and agreements made, it can be difficult to discern exactly what happened after the initial 1840s plan to relocate the University of Glasgow. This article draws on two substantial texts, Stella Matko’s 1985 dissertation Glasgow University Removal: Scott on Gilmorehill, and Nick Haynes’ 2013 Building Knowledge: An Architectural History of the University of Glasgow. It attempts to clarify what happened (always allowing, however, for new and conflicting evidence to emerge), and the involvement in the original 1840s plans by John Baird I and his chief draughtsman, Alexander Thomson, to relocate the College.

The plan to move

As early as the 1830s, discussions took place about the future of the College on its historic site:

the medieval and Renaissance buildings clustered around the High Street, Trongate and Gallowgate, [had] descended into a slum of overcrowded workers’ housing, with little sanitation or fresh water. Apart from constant outbreaks of typhus and cholera, poor health conditions were further compounded by appalling atmospheric pollution from the many coal-powered factories1.

To the north, the St Rollox chemical plant, the largest in the world, burned 30,000 tons of coal a year; the Molendinar Burn, running through College grounds, was ‘a toxic semi-enclosed sewer’2.

Even in the 1820s, the College’s Clerk of Works had signalled the difficulties of repairing crumbling stonework on the older buildings, nor had much work been done since to renew them. New buildings had been erected, but even the latest ones dated to some years before: William Stark’s Hunterian Museum in 1804 and Peter Nicholson’s Hamilton Buildings in 1811.

There was much to admire in the existing College grounds, including what was described in the course of a visit by the Duke of Cambridge as ‘the spacious square behind the College and in front of the Hunterian Museum’ (the Duke’s carriage entered the grounds by mistake via a secondary entrance past the professors’ lodgings rather than main gate under the tower, so the Lord Provost, baillies and councillors, the Principal, members of the Senate and other dignitaries had to rush to the back of the College to welcome ‘the Royal Duke’3.

While some mourned the loss of the ancient buildings, others took a more pragmatic view:

‘The present position of the College is far from being what it ought, as the site of a seminary of learning. It stands in the centre of one of the most densely peopled districts of the city - in point of health, both as regards professors and students, it is highly objectionable; its close proximity to lanes so pestilent, morally and physically, as the Havannah and the Vennels, bars it from everything exteriorly pleasant or agreeable; while it is now at a very inconvenient distance from the homes of a great majority of the students.’4.

The College and the Railway Companies

The first approach to the College from a railway company did not, in fact, require wholesale removal. On 28 August 1845, the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands Junction Railway Company approached the Faculty ‘with a view to obtaining a hundred yard wide strip of land to run through the college grounds’5. The strip could be to the north or the south of the existing College buildings, but it needed at least to allow for a terminus on High Street.

The Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands was moving quickly: it had only recently been launched, backed by several influential Glasgow businessmen, including two members of James Finlay & Co., James McCall of Daldowie, and backed by the Royal Bank of Scotland and Coutts & Co. With £400,000 of proposed capital, they planned a direct line from Airdrie to Glasgow, ‘terminating on the East side of the City, as near to its centre as possible’, also to connect ‘the great Mineral Districts of which Airdrie and Coatbridge form the focus, with the South Quays of the Harbour of Glasgow, by a Branch to the Clydesdale Junction Railway’, and finally to connect ‘by the same means, and by shorter routes than any yet projected, the Caledonian Railway with the Eastern portions of the City of Glasgow’6. The Parliamentary legislation required for these three ambitions was enacted successively in 1846, 1847 and 1848.

They faced competition, however: in the same newspaper, the Airdrie & Bathgate Junction Railway, with half the planned capital of the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands, their plans were less clear: from Airdrie, they proposed to ‘make connexions with the existing and projected Railways, by which that important town and district are, and still farther to be united with the city of Glasgow; and will terminate at Bathgate’ from where a connexion would be made to the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway.

To counter the opposition, the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands upped the ante, either proposing (according to Matko) or being offered by the Principal (according to Haynes) to acquire the whole of the College site in exchange for building a new college on Woodlands (below) to the west of the city. They would purchase 17 acres of the 23-acre Woodlands estate and pay for classrooms, laboratories, a library, a museum and a chapel. The College’s medical professors objected: they demanded a new hospital adjacent to the new building ‘as the distance from the Royal Infirmary would be inconvenient for the teaching of students’ (and presumably also for the teachers).

Such wholesale removal would require legislation. By November, it was reported that

‘The exact terms of the arrangement have not yet transpired; but we understand that Woodlands has been purchased for £27,000, subject to a feu duty of £180 per annum; and we have heard it stated that the purchase money of the present College, with the grounds attached, will be £105,000’7.

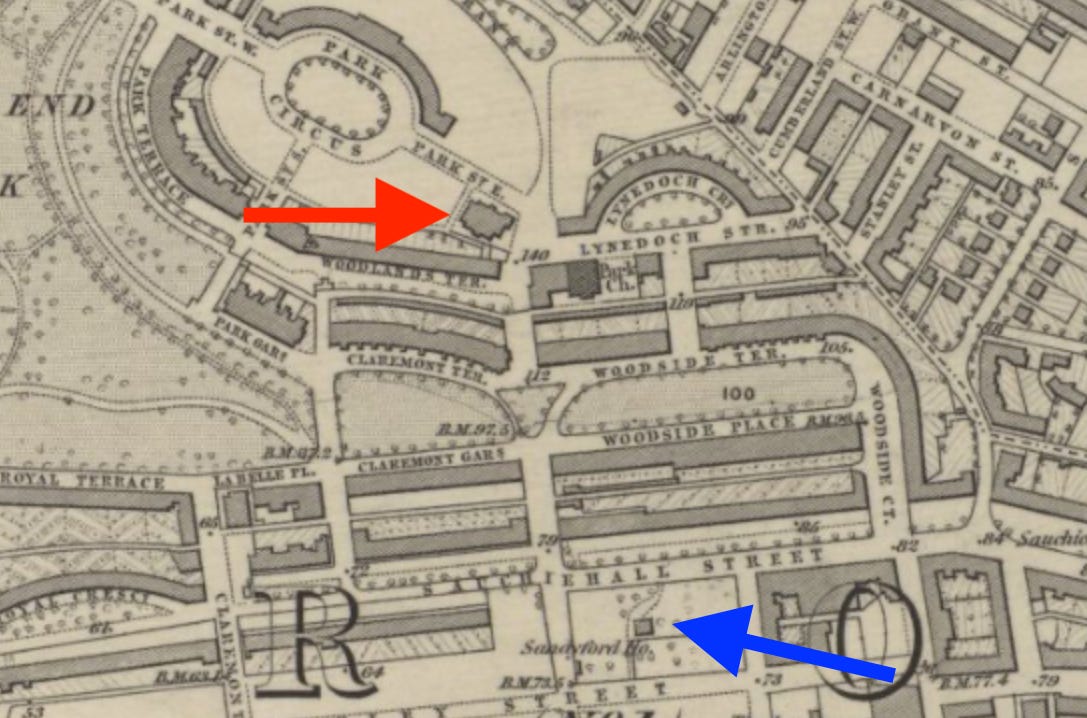

Not only that, but the Railway Company, having demurred at first, finally agreed to pay £10,000 towards the cost of building a hospital on Sandyford, to be purchased by the College, and to pay £500 a year thereafter for maintenance. Sandyford House, shown by the blue arrow in the 1856 Ordnance Survey map below, stood on its own grounds south of Sauchiehall Street, previously called Sandyford Street at this location. Although not adjacent to the College site, the new hospital would not be too distant. The red arrow shows Woodlands, the majority of whose estate would be sold off. By 1856, the north and north-east lands remained empty; Charles Wilson’s Park development was gradually populating those to the south and west.

The Bill appears to have been introduced for the Parliamentary session in January 1846 as

‘An Act to enable the College of Glasgow to effect an exchange of the present Lands and Buildings belonging to, and occupied by, the said College, for more sufficient and adequate Lands and Buildings more advantageously situated, and for other purposes relating thereto’.

Presumably, on the basis that the new legislation would not encounter any difficulties, the Company’s agreement with the College stipulated that everything should be ready to allow it to proceed within two years from July 1846. Royal Assent to the Act was received in August of that year.

With the Act secured, other railway companies continued to show interest, just in case the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monkland arrangement fell through: the West of Scotland Railway Company proposed running a line across the Clyde ‘above Hutchesontown Bridge and going through the public green [Glasgow Green], so as to form a general terminus on the ground presently occupied by the College buildings’8.

Even the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monkland was exploring other, perhaps cheaper, options: in mid-1847, it proposed a similar scheme to that of the West of Scotland Railway Company but constructing a viaduct to cross the Green. This proposal met widespread public and Town Council opposition: there were the issues of ‘gradients, curves and other engineering difficulties, and the damage to the property through which the line would pass to consider’, while purchasing the area of the Green required would cost a minimum of £60-70,000 from a company whose total capital, it was claimed, did not exceed £105,0009. If railway companies could cross public parks in Glasgow, what did that mean for other cities? And was this a means of getting out of the College deal and its demolition costs and instead building a terminus on open land at the bottom of Saltmarket:

‘Instead of making any sanitary improvements in the vicinity of the College they would be quite the reverse - they would by the erection of warehouses etc., completely block up the only large open space which now form the lungs of the wynds, lanes and alleys in that locality. As to the number of houses of an inferior description of taken down in the line of railway, there were only ten old houses’10.

Baird’s first plan

The Glasgow, Airdrie & Monkland moved quickly, commissioning John Baird I to draw up a set of initial plans by 17 December 1845, submitted to the Dean of Faculty over the Christmas holiday. In the 1830s, Baird had produced a layout and designs for the adjacent lands of Clairmont and South Woodside, so was familiar with the topography; he was also noted for completing buildings on budget.

These drawings were offered with an open acknowledgement of the need for a detailed response, possibly reflecting Baird’s limited knowledge about precisely what the College authorities and staff would be looking for. In January 1846, they were reviewed by the Faculty: they showed ‘an E-shaped building in the Scottish style but classical internally, with elevations in the style of an Italian Renaissance palace with “Scottish Baronial” accretions’11. The block faced southeast: the tongue of the ‘E’ contained the Library and museum; two lodges flanked the main entrance, and the Professors’ lodgings were a single block behind the main building. The Professor of Divinity, who had larger accommodation than the other Professors at the existing College site, complained that he also needed more space at the new one.

The Faculty decided to submit the plans to William Playfair of Edinburgh requesting him to consult with both the Principal and Baird as to any alterations that may be desirable in order that Mr Playfair may be able to estimate the probable expense of the proposed buildings. The Principal wrote to the Railway Company to ascertain if they would be willing to defray the costs of consulting Playfair. While awaiting a reply, the Faculty examined the plans and it was noted that the Professors’ houses were inadequate in terms of accommodation. The library and museum were too small and the floor between them should be “arched” so rendering them more fire-proof. Baird was asked to present a comparative statement of the present accommodation for the museum and library and the accommodation afforded by the proposed plan. The Faculty noted the lack of a chapel, which they considered could be accommodated within the Divinity classrooms until a separate chapel was obtained if “fitted up in a superior and suitable manner”12.

Principal Macfarlan requested that the Railway Company pay for him and Baird to consult Playfair in Edinburgh. He did so on the advice of the College Rector, Andrew Rutherford, possibly because Playfair had worked on Robert Adam’s designs for the Old College in Edinburgh twenty years before, as well as Heriot’s Hospital and the more recent Donaldson’s Hospital, but probably also because Playfair had altered Laurieston Castle for Rutherford the previous year.

Playfair responded quickly. commenting that he ‘did not choose to work upon another person’s plans’13.

The College Faculty asked Baird to consult someone else on the plans. Haynes notes that the names of Decimus Burton and Edward Blore appear in a pencilled marginal note in the Faculty minutes. Both were London architects: Burton had designed a housing layout for the Kelvinside estate the previous decade. Baird chose the latter, possibly having met him in connection with Blore’s work on the great west window in Glasgow Cathedral that year.

Unlike Playfair, Blore seems to have had little reticence about responding. Although his letter is addressed to the Principal, it seems likely that Baird approached him directly. Blore’s criticisms of the plans were specific:

I have come to the conclusion that they are by no means sufficient for the purpose proposed and that they are deficient in the following particulars:

1. Changes which ought to be made in the construction and materials proposed to be used;

2. Further information required for the complete understanding of the material and mode of performing the works;

3. Works which have been altogether omitted and which require to be provided for the complete fulfilment of the proposed arrangement under the first heads14.

Whatever the shortcomings of Baird’s December 1845 plans in terms of meeting the College’s specifications, he had clearly gone into some detail, although not enough for Blore. Blore’s changes were largely technical and practical, including replacing red pine window frames with oak, which was also prescribed for all interior and exterior doors and staircases, and strengthening the classroom floors: ‘neither the drawings or specifications furnish sufficient information to satisfy me that this has been sufficiently attended to’. He noted that red pine, white deal, and white pine were proposed in the construction, ‘but the parts of the building in which the materials are to be used is not specified’, nor could Blore determine from the drawings which parts of the structure were to be of stone, brick or wood. He seemed to prefer oak throughout.

Many of Blore’s comments focus on ensuring the strength of the building, as well as seeking information about the heating and ventilation of classrooms. While he liked the elevations, he was concerned about how well they would be executed:

The Elevations shew to the eye very costly and elaborate facades, but unless the character and style of the mouldings, ornaments and details are executed with boldness, depth and correctness of character the promises of the Elevations will be decomposited(?) in the execution. There are no detailed drawings explanatory on this point.

Nor was there a section of the tower, nor any drawings to show the design of the lodges or the professors’ accommodation within: ‘No Bellhanging appears to be provided’, nor any ‘shutters or fastenings’; he also looked for and did not find drawings of the roof floors. Finally,

There does not appear to be any large reservoir of water. Such a reservoir would be useful in case of fire, and might also be rendered available for scouring out the drains, a point of great importance where so many people are occasionally presented(?) together and the drains are likely therefore to become foul.

But which drawings are we talking about? Haynes states that the plans submitted in December 1845 have not survived, and the plan above, which Haynes identifies as belonging to ‘the first Woodlands scheme’, is dated June 1846. But Blore’s letter was written in May 1846 and focuses on technical issues, not on the design. What seems likely is that Baird re-drew his plans in June 1846 to respond to inputs from the Faculty and Blore, but that the basic design, reminiscent, as Haynes states, of Playfair’s Donaldson’s Hospital and remodelled Heriot’s Hospital, as well as bringing in roofline elements from the College’s existing High Street frontage, remained essentially the same.

Baird’s second plan

There is a reference to Baird taking up Blore’s comments with the Faculty, detailing the sizes of the iron beams required for the revised structure. But Baird then took his plans further, and it is unclear why.

On 30 October 1846, Baird submitted his revised plans to the Faculty. For Plan 2, the detailing became much more elaborate, especially for the tower and at the roof line, and with an added porte-cochere. Haynes details the physical changes - a self-contained chemistry block, room plans, and changes to the library and museum, all of which Baird Baird presented to the Faculty in person.

Baird’s new scheme consisted of a rectangle enclosing two quadrangles 100 x 110 feet in dimension. The elevations were designed in a hybrid style with Italian and Scottish features. The Faculty approved the plans and sent them to the Treasury for its consideration15.

Given the Faculty’s approval, given on 30 December 1846, Baird might have thought things were moving forward. But the College Removal Act, assented to four months earlier, required approval by a committee comprising the Chancellor, Rector and Principal, among others, and separately by the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury, the latter with their own architectural advisors. The Treasury believed the plans needed to be reviewed again, this time by architects with whom they were probably more familiar. On 17 February 1847, the Lords Commissioners sent both the first and second set of plans to Sir Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin, then engaged in building the Houses of Parliament.

Pugin disapproved of the architectural style, not because it was a concoction but because it was a concoction with no Gothic ingredients. Barry's opposition was less determined. John Richardson who met the latter at the Treasury wrote to James Mitchell, “Mr Barry seemed struck with the beauty of the elevation but alluded to Mr Pugin’s dislike of buildings of combined Italian and Saxon architecture”16.

In fact, the second plan fared worse than the first: the first scheme lacked ‘purity of style and was not of a high class of art or in any respect very meritorious’; the second ‘apart from consideration of the additional accommodation which they afford we consider… as a whole more objectionable than that of the original design’17.

Their recommendations a few weeks later were to enlarge the quadrangles to provide more air and light and to relocate the Professors’ lodgings so as not to block the light to the rear of the building. The Faculty’s view was that Barry and Pugin’s objections were based on insufficient knowledge of the proposed site and of the College’s physical requirements They hoped that these objections might be removed by explanations which they were readily able to furnish18.

By April 1847, Baird had travelled to London to meet Barry. To respond to Barry and Pugin’s criticisms, the Faculty and Lords Commissioners asked Baird for a third set of plans on a revised layout.

Baird’s third plan

In his third plan, of August 1847, Baird changed his layout to comprise a large rectangular block with a single quadrangle.

The library and museum were housed in the north-east of the building where they would be provided with more space. The Professors' houses were to be moved from the back to the front of the building in two blocks facing each other across the entrance. With this new set of plans, Baird provided a second set of elevations. These were still in the Renaissance style showing no stylistic departures from his first set19.

In Plan 3, the porte-cochère from Plan 2 disappears, and there is some reworking of the end pavilions and additional chimneys, but at least stylistically, everything else remains the same.

On 4 August 1847, the Faculty reported that ‘when Mr Baird should have prepared revised plans embodying these changes, Mr Barry would revise the elevations’.20 However, this did not happen. Instead, perhaps with a desire to press ahead,

The Faculty approved of Baird’s revised plans and authorised the Committee to proceed with the measures required for obtaining the sanction of the Treasury as speedily as possible21.

On 25 August, the plans were submitted to the Treasury, which actually approved them in principle. However, the Treasury, probably on advice from their architectural advisers who had not, it seems, ever seen the site, considered this more elaborate proposal would cost too much.

If Barry was still in the picture, he might have turned down the opportunity to revise Baird’s elevations owing to other commitments. By late 1847, he was completing the rebuilding of the Treasury in Whitehall (now the Cabinet Office) and was in the middle of work on Bridgewater House in Westminster, with its 144-foot frontage. At the Palace of Westminster, the House of Lords had been completed the previous April, but work on the House of Commons would continue for another five years.

In February 1848, the Treasury approached Edward Blore to review the elevations and structure for a fee of £300, specifically to bring down the building cost.

Blore’s work must have taken some months since it was not until 27 February 1849 that the Treasury approved Blore’s simplified elevations,

After they had been reassured at length that the expense of the new college buildings according to Blore’s elevations and structure and Baird’s plans would not exceed the cost of executing Baird’s original plans by more than ten per cent, in agreement with the Railway Company. It was now hoped that the building work would proceed as originally agreed with the Company.22

With Blore’s changes, the estimated cost of the new building was £85,200, to be largely offset by the sale of the High Street site. It is unclear whether the Faculty were asked to approve Blore’s changes, although it is presumed that they did so.

The collapse

It was now that everything fell apart. Relations between the College and the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands Railway Company had not always run smoothly: at some point, the College had written to the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands Railway Company stating that it could not proceed in taking over the College site if the College Bill had not passed into law; the Company responded quickly, stating that it intended to take over at least a portion of the College site for their terminus even if the Bill failed to become law23.

In January 1849, the College approached the Company to pay its share of the purchase cost of the lands of Sandyford for the intended hospital. The Company replied that it now considered itself free of any obligations to the College: their contract stated that all arrangements had to be finalised within two years from July 1846, which was six months earlier.

By the end of April, the College proposed to take the Railway Company to court. At that point, it was made clear that the Company was in no financial condition to honour any part of the agreement.

In November 1849, the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands Railway Company was proposed for dissolution, in the process freeing itself from any obligations to the College and seeking the relevant legislation to be amended or repealed24.

The Railway Company’s position was not without its detractors: they may have blamed economic conditions for its withdrawal from the agreement with the College; others saw conspiracy, especially when it was claimed that the Chairman of the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands, Peter Blackburn, was also Chairman of the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway, which had been quietly buying up shares in its rival. Nor was such suspicion helped by the Chairman’s following reported comments at the Company’s shareholders meeting held in March 1850:

It did seem to him rather hard that a respectable, learned and venerable body, such as the Professors, should wish to remove the College from the ground where it had stood for hundreds of years, and which had been visited by Royalty itself, by taking advantage of some expressions in an act of Parliament, which gave them a right to be well paid for the ground, if it was necessary for this Company to take it. They were certainly entitled to be set free from all the expenses into which they might have been brought, and, perhaps, a sum of money might be given them to do some little good to the College25.

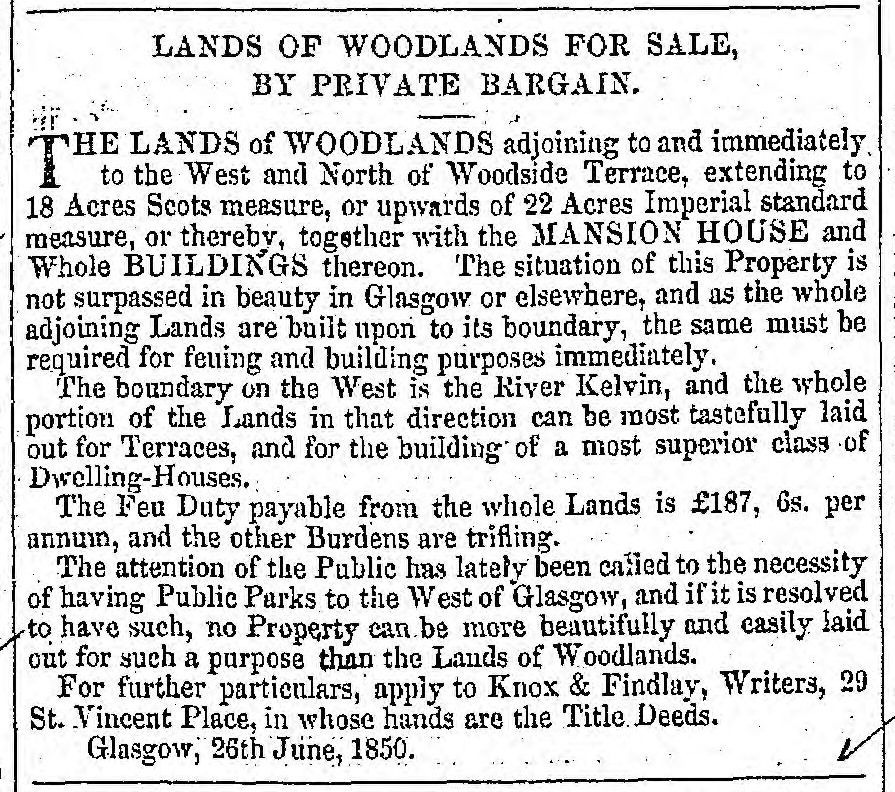

The writer hoped that the College would press on with its legal action, but in May 1850 it was reported that the agreement had been annulled26. The following month, the Woodlands site was put up for sale27: it had presumably already been purchased by the Railway Company since the firm advertising the sale was the same one that issued the notice of dissolution six months earlier.

Ultimately, the Railway Company agreed to pay £12,700 to compensate the University for expenses incurred. £10,000 of this was set aside for a Fabric Fund. But it never paid Baird, and Haynes claims that Alexander Thomson’s resentment almost two decades later over the College’s arbitrary choice of George Gilbert Scott to design its new buildings stemmed in part from that and from the affair’s effect on Baird’s health: Baird had died in 1859, aged 64.

Baird’s designs

In truth, Baird’s designs appear, especially in their later stages, as unnecessarily complicated and fussy. Both Cairnhill House, Airdrie (below), and Stonebyres House, Lesmahagow, on which Baird worked in the 1840s, together with Playfair’s larger Donaldson’s Hospital and Heriot’s Hospital, suggest what he was drawing on.

To that extent, Blore’s changes, mostly involving cutting away extraneous details and finials, result in a more restrained, admittedly less immediately inspiring frontage: delete the Scottish references (Haynes calls Blore’s work ‘competent, but rather flat and dull in comparison to Baird’s second scheme’). What Blore aimed at could be seen as prefiguring his 1850 design for the frontage of Buckingham Palace.

That said, Woodlands was not Gilmorehill: the former site faced an open space, as seen in Plan 2, facing southeast (in Plan 3, the main entrance to the College would be flanked by two terraces of Professors’ lodgings). Baird’s College faced towards the city centre with its back to the lands descending to the River Kelvin, the reverse of Scott’s Gilmorehill with its south-southwest facing frontage, and therefore with its main entrance looking into open parkland, never intended to be built upon. Today, to enter Scott’s University through its tower entrance requires passing by Pearce Lodge to the west, along the eastern front on rising ground facing Kelvingrove Park throughout. That approach may give a grand view of Kelvingrove, the Park terraces and the Clyde, but it means that most students and lecturers enter Scott’s building through its backside.

In 1975, a Glasgow University publication offered a view of how Baird’s work would influence George Gilbert Scott’s own designs two decades later:

When the New College Buildings Committee recommended Scott as the architect, they were probably influenced by the fact that he, more than any other, had experience in planning large buildings. In spite of their previous dissatisfaction with a local architect, the Committee sent Baird’s plans to Scott. Doubtless these affected his design and his layout shows remarkable similarities. The first set of Baird’s plans with its open quadrangles compares with the originally open west quadrangle of Scott’s building; the second set is recalled in the two quadrangles and clock tower arrangements; and the third set in the location of the Library and Museum28.

But there was no ‘dissatisfaction’: the Faculty twice approved Baird’s plans. Pugin may have disliked them because they weren’t Gothic; Blore was paid to make the elevations less costly, although there are doubts as to whether Baird’s plans as executed would have exceeded the budget. However, had Baird’s second or third plans succeeded, the amount of external stone detailing might have resulted in the same maintenance challenges that have beset the Houses of Parliament for years. Baird might have been persuaded - especially by the Glasgow, Airdrie & Monklands Railway Company directors - to cut back on them to keep costs down. Such challenges were ones which Thomson, whatever actual hand he had in the three sets of plans, would also become aware of in his future practice.

However, even while reworking plans for the College, Baird obtained some recompense. The proposed move accelerated Woodlands as a site for development. In 1842, he had designed Beresford House and Claremont Terrace, and 1845 Lyndedoch Place and Lynedoch Crescent. In 1849, he designed 1-17 Woodlands Terrace. All these were on the approaches to the intended College site, although architect Charles Wilson would obtain the greatest benefit.

N Haynes Building Knowledge: An Architectural History of the University of Glasgow, Glasgow and Edinburgh, 2013. Although highly detailed and published by Historic Scotland, the Index conflates Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson with his near-namesake and contemporary, the architect and civil engineer Alexander George Thomson, who reconstructed the former entrance to the Old College as Pearce Lodge on the University’s new site.

ibid.

Glasgow Herald, 23 Sep 1844

Glasgow Courier, 23 Nov 1845

Stella AM Matko, Glasgow University Removal: Scott on Gilmorehill, Glasgow University dissertation, 1985, from whom much of what follows is taken, but who appears to err in some of the dates provided

Glasgow Chronicle, 29 Aug 1845

Glasgow Courier, 23 Nov 1845

Glasgow Courier, 12 Nov 1846

Glasgow Chronicle, 9 Jun 1847

ibid.

A Ross, J Hume, A new and splendid edifice: The Architecture of the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, 1975

SAM Matko, op. cit.

W Playfair, 21 Feb 1846, in Glasgow College Minutes of Faculty 1839-48

W Blore to the Principal, 30 May 1846

SAM Matko, op. cit.

ibid.

N Haynes, op. cit.

Minutes of Faculty for 30 Apr 1847, op. cit.

SAM Matko, op. cit.

Minutes of Faculty for 4 Aug 1847

ibid.

ibid. The Treasury’s decision, published in the Edinburgh and London Gazettes a month later, was dated 24 March 1849

Matko dates the exchange to January and February 1849, but the Act had received Royal Assent some 18 months before.

Reformers’ Gazette, 17 Nov 1849

Reformers’ Gazette, 6 Apr 1850, emphasis in the original

Glasgow Herald, 24 May 1850

Glasgow Herald, 28 Jun 1850

A Ross, J Hume, op. cit.