When Alexander Thomson delivered his series of four Haldane Lectures in Glasgow in 1870, his talks commemorated a Glasgow-based engraver who, ten years before his death in 1843, had created the Haldane Academy Trust as a private charity to support the study of fine arts.

James Haldane’s initial list of Trustees (see below) drew heavily on Glasgow’s wealthy and influential mercantile classes, reflecting someone who was well-connected to the city’s commercial life in the first half of the 19th century. His background, however, was far removed from this.

James Haldane was born in Kilmaronock, Dunbartonshire, about May 1767, and was baptised in the parish church on 3 June 1767 as the first surviving son of William Haldane and Christian Batison (another James had been born, and presumably died, the year before). His likely birthplace was Little (or ‘Meikle’) Badshalloch, where his father was farming in 1770, a short distance from the parish church and adjacent to the military road leading from Balloch past Drymen and Balfron to Stirling1.

There may be some family connection between his and the other Haldane families in Drymen, but the precise relationship isn’t known at this stage.

James’s father, William, attended the local parish church but was not always in sympathy with the minister: in 1770 he was one of several objectors to the appointment of the Rev. James Addie as minister, based on the content of his sermons. Several parishioners left to construct a Relief church, but William Haldane remained, although four years later he refused to be appointed by Mr Addie as an elder2.

William and Christian had at least three further children, two sons and a daughter, but only the last, Margaret (born in 1771) appears to have survived to marry and have children.

There is no information known on how James learned his craft, but he must have had a precocious talent: at the age of 22 he was listed as ‘Haldane J. and co. engravers and copperplate printers, Argyle-street’ in Jones’s Directory of 1789. The ‘and co.’ suggests there were partners involved (at this time, the term ‘company’ essentially meant a co-partnership). He would spend the rest of his working life based out of either Argyll Street or the adjacent Trongate.

As to what he did, we know remarkably little. In 1802, he engraved the membership certificate for the newly founded Glasgow Philosophical Society, with Peter Nicholson as one of its initiators (Haldane was member No. 51). Alongside the standard fare of engraving business and personal stationery he also engraved copies of well-known artworks: the estate sale after his death included engravings of paintings by Rembrandt and Hogarth, among others.

The Glasgow Bank Company

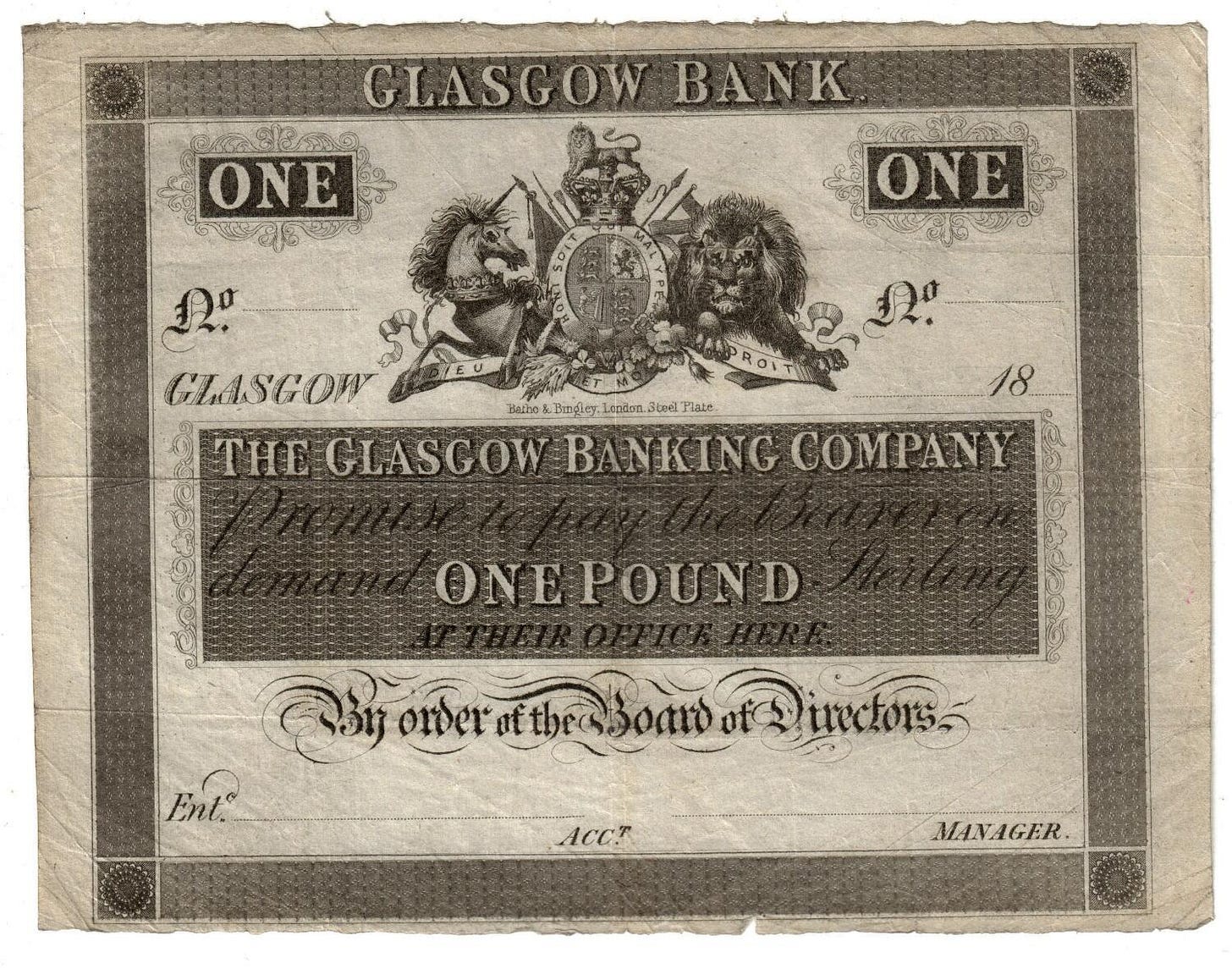

After its formation in 1809, Haldane engraved banknotes for the Glasgow Bank Company. He may also have engraved the much simpler cheque design used by the Bank.

The Glasgow Bank Company was ‘the last bank of the old private-partnership type to be formed in Glasgow’, with an initial sixteen partners (mostly from outside Glasgow) who subscribed £200,000 in forty shares of £5,000 apiece, and with offices at the corner of Montrose and Ingram Streets3.

Of two known examples of Haldane’s £1 banknotes, however, both are dated 1 May 1830 and appear to show the signature of its chief cashier, William Burridge Cabbell (1773-1840), who had been with the Bank since its foundation (Haldane’s name appears under the shield). Both, however, are marked ‘Forgery’. The banknote below appeared in a 2016 sale by Spink & Son, marked as ‘possibly genuine’ and with an auctioneer’s estimate of £250-300.

The problem of forgery

Counterfeiting was a major problem for banks, and forged versions of Haldane’s note had been in circulation since at least 1824: when Elizabeth Lowden – with at least three aliases - was found guilty in Perth of issuing a forged note and sentenced to be transported for seven years, she asked if she could take her young daughter with her4. Two years later, Agnes Cann was charged in Glasgow with issuing two forged banknotes of the Glasgow Banking Company and one from the Royal Bank of Scotland5. The penalties for ‘uttering’ forged banknotes were severe: in 1826 ‘Mary McDonald, alias Flanigan, or Docherty’ was sentenced to transportation for seven years, as was Daniel Black two years later6 while Paul Selfridge, convicted the following day, was transported for life. In Ellon, Aberdeenshire, when two men were arrested in 1828 with a hundred newly forged one pound banknotes, most were from the Glasgow Banking Company7.

When designing ever more complex banknotes, in the early 19th century, engine turning (or guilloche) was the answer: machine engraving precise geometrical patterns and designs onto metal such as copper or steel. The process had been used for metalwork for some years and, using a mechanical Rose Engine or ‘Decorative Lathe’, an unlimited variation of patterns could be created and precisely engraved.

During the latter half of the 18th century, the practice of engraving wood, ivory or metal on a lathe had become fashionable among the aristocracy and upper classes as part of a wider interest in the use of machinery as a means of personal expression as well as commercial enterprise: Peter the Great, Kings Christian V and Frederick IV of Denmark, George II’s daughter Princess Louise, then George III, were all ornamental ‘turners’, although it was France where the art became especially widespread, practised by Louis XV and, to a lesser extent Louis XVI who said, “By relaxing with a mechanical art, I believe, after my Royal duties, I come closer to the lower classes, who are also a part of my great family”8.

Haldane’s banknote design was relatively simple, however, with a repeating border on three sides, but it was only after almost a decade of forgeries being produced that the bank took action, and when they did so, James Haldane was not part of the solution:

‘The Glasgow Bank Company have withdrawn from circulation all their old one-pound notes, viz., plain with brown margin and blue stamp in the centre, and the public are cautioned against taking any notes of that description. The only one-pound notes now issued by the Glasgow Bank Company are from a beautiful plate, engraved by Messrs Perkins & Bacon, of London, and all of them are signed by Alexander Todd, cashier, and by James Watson, accountant’9.

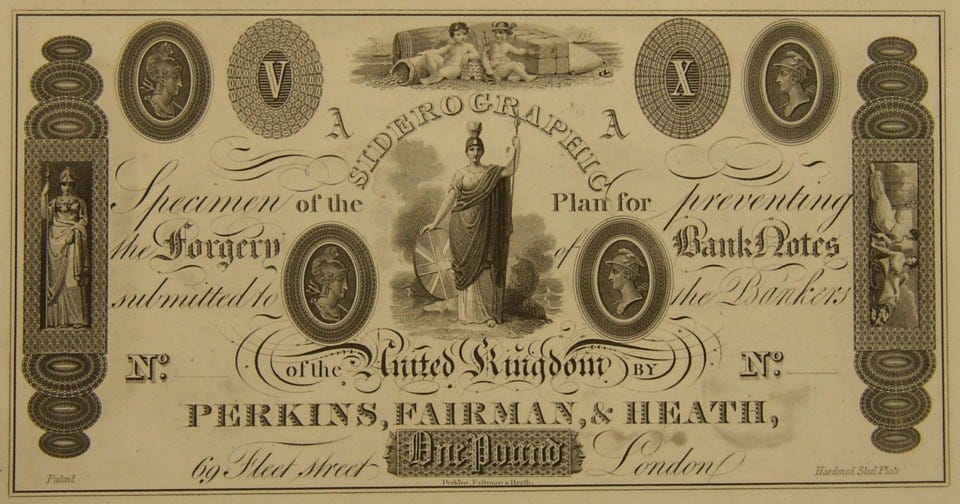

Not only could London engravers produce more complicated banknotes, but they did so by engraving on steel rather than copper (see below). The latter could only produce a few thousand impressions before being worn out, while steel lasted much longer, and by copying further steel plates from an original, the quantity of identical banknotes able to be printed was almost unlimited.

In 1836, the Glasgow Bank Company merged with the Glasgow-based Ship Bank, which employed the London firm of Perkins, Fairman & Heath. Back in 1821, this company had produced a specimen design for the Bank of England which was not accepted, but, as Perkins, Bacon & Co, they would design and engrave notes for banks across the United Kingdom and overseas and become more widely known as the engravers and printers of the 1840 ‘Penny Black’ stamp.

The aristocrat and the lathe

Among those willing to take up the challenge of forging these ever more complex designs was William Cunningham Cunninghame Graham, 7th of Gartmore and 16th of Ardoch, born on 16th August 1775 at Gartmore in Perthshire.

Cunninghame Graham (sometimes hyphenated, sometimes not) joined the Prince Regent’s set in London, losing much of his family’s wealth through gambling. He was later described as ‘a first-rate turner and mechanician. He formed and fashioned his own tools with surpassing ingenuity, and invented a contrivance by which he was able to trace copies of not only the rarest engravings of Raphael Morghen, but the choicest masterpieces of Domenichino and Guido Reni10. He soon discovered, however, that this contrivance might answer a more profitable purpose - that of counterfeiting, with astonishing exactness, the signature of bankers’11.

On 21 June 1811, Cunninghame Graham purchased a lathe from one of the foremost manufacturers of the day, Holtzapffel & Co., based in London, who produced more than 2,500 lathes over a 120-year period. Cunninghame Graham purchased Holtzapffel Screw Mandrel No. 722, for which he paid £241 10s 0d (equivalent to approximately £14,000 today), together with several lathe heads (No. 733). However, forged cheques or banknotes were traced back to him, although the defrauded banks preferring him to make restitution rather than having him taken to court. In late 1826 he was made bankrupt and obliged to enter into a trust agreement with his creditors12. The contents of Gartmore house, auctioned in January 1827, included ‘Two excellent Turning Lathes, with full assortment of Tools’13.

Cunninghame Graham was undeterred, however: fleeing Scotland for Brussels and then Florence - leaving behind him the nicknames ‘Bad Willie’, ‘the Runaway Laird’ and ‘The Swindler’ - a decade later he became involved in a Europe-wide scheme to steal more than £1 million through forged letters of credit drawn on the London bankers Glyn, Halifax, Mills & Co. The scheme ultimately failed but led to a famous libel trial (Bogle versus The Times) in 1841 when one of his co-conspirators tried to clear his name (that failed too). As before, Cunninghame Graham was not brought to trial. He even returned to London, dying there in 184514.

As for Holtzapffel Lathe No. 722, it was purchased by James Haldane, presumably together with the lathe heads No. 733. Haldane must have made use of it since he was reported to have made several improvements and additions by the time it was sold at his own estate sale in April 1844.

The Expert Witness

Haldane also became something of an expert witness in court cases: in 1820, he was brought into the ‘Radical Rising’ case, looking at a ‘Provisional Government’ broadsheet and tasked with finding out which printer was responsible. Together with the editor of the Glasgow Chronicle and a Glasgow printer, they identified Duncan Mackenzie’s press at 20 Saltmarket as the most likely source. Unfortunately, Captain Mitchell, the man leading the investigation, had his eye fixed on William Lang of Bell Street, “a known Radical who had offered to print a Radical Reform newspaper at a meeting the year before”, and arrested him despite the evidence to the contrary. Mitchell only backed down when Haldane and his colleagues threatened to expose his actions. Lang was released and Mackenzie arrested, being held for a week charged with “printing and publishing the treasonable address” before being released15.

In 1828, Haldane was called to Edinburgh as a witness in the case of Kingan vs Watson, arising from anonymous letters circulated in Govan between 1822 and 1825, claimed by Robert Watson of Linthouse, a banker in Glasgow, to have been written by John Kingan, a Glasgow merchant. The damages claimed were £10,000; Watson was awarded one shilling16.

Haldane’s Income

Overall, Haldane’s career must have been a successful one, evidenced by the property included in the estate sale after his death in 1843. Catalogues were made available in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London, and Dublin. Among the paintings available on the first day of a five-day estate sale were those by Correggio, Claude, and Gainsborough, as well as Italian, Flemish and Dutch painters. Apart from Rembrandt and Hogarth engravings, a set of Napoleon Medals in bronze (“the most perfect in the Kingdom… cost originally 150 Guineas”) and the Holtzapffel lathe (mistakenly identified as a more complex Rose Lathe), “with many useful improvements made on it by the late Mr. Haldane… pronounced by eminent judges to be unequalled in Scotland, and cost originally 600 Guineas” (it didn’t, and sold for £170). Generally, however, bidding was strong for many pieces.

Other property sold included copperplates ordered but not yet paid for and collected, and Haldane’s property in Argyll Street (opposite the Buck’s Head Hotel, comprising six rooms and kitchen plus two cellars).

Some of his wealth may have come from his advantageous marriage in 1810 to Margaret Thomson, daughter of George Thomson (1751-1837) a Glasgow merchant and banker, and a founding member in 1783 of Glasgow’s Chamber of Commerce. Her grandfather was Andrew Thomson of Faskine, who in 1785 left off as a partner in the Glasgow Ship Bank to start his own bank under the name of Andrew, George, & Andrew Thomson (the father and two sons). Like many other businesses, the bank failed a few years later in the wake of disruption to trade caused by the French Revolution, but the family’s wealth allowed all creditors to be paid in full17.

The Haldane Trust

There were no children from his marriage, and in 1833, a decade before his death, James Haldane developed the idea for a trust to be used to support education in the fine arts.

The Haldane Academy Trust, drawing on funds allocated by Haldane before his death and the income from his estate sale after it, was used to help expand the Glasgow Government School of Design, founded in 1845 at 12 Ingram Street (at the northwest corner of Ingram and Montrose Streets), which in 1853 became the Glasgow School of Art.

The principal benefit for the School came from the Trustees negotiating with Glasgow Corporation for accommodation in the 1855 Corporation Buildings in Sauchiehall Street, enabling to move there in 1869 and matching the rent paid to the Corporation by the School. The Trustees also introduced various student prizes and awards, for which it appointed its own examiners. The Trustees arranged special lectures on art and architecture, the Haldane Lectures, with ‘Greek’ Thomson, one of the Trustees, delivering a series of four lectures in 1870. The terms of the Trust required that its name be incorporated into the School’s title as the ‘Glasgow School of Art and Haldane Academy’, but that was dropped in 1891 as the name was proving confusing.

The Trustees

Haldane’s trustees as listed on 14 June 1833, were divided into three classes: twenty-five merchants, manufacturers, and bankers; twenty-five professional men, tradesmen and amateurs; and twenty-five painters, sculptors, engravers, carvers and gilders architects, modellers, etc. (A later article will look at the trustees and their professional and familial connections with Alexander Thomson).

First Class:

James Oswald of Shieldhall

James Ewing of Dunoon Castle

Kirkman Finlay of Castle Toward

Henry Monteith of Carstairs

James Dennistoun of Golfhill

William Dunn of Duntocher

Alexander Garden, merchant in Glasgow

Robert Scott, banker there

Andrew Rowan, banker there

Archibald Bogle of Gilmorehill

Henry Houldsworth of Cranstonhill

William Maxwell, of Dargarvel

William Hussey, cotton-spinner in Glasgow

Alexander Dennistoun, younger of Golfhill

John Miller, merchant in Glasgow

James Smith of Jordanhill

R Douglas Alston, merchant in Glasgow

George Alston, merchant there

Robert Bartholomew, cotton-spinner there

Peter Hutcheson, manufacturer there

James Hutcheson, manufacturer there

Archibald Smith, merchant there

James Finlay, merchant there

John Finlay, merchant there

John Wright, junior, merchant there

Second Class:

Sir Daniel Keyte Sanford, Professor of Greek; Dr William J. Hooker, Professor of Botany; Robert Buchanan, Professor of Logic; Dr William Cooper, Professor of Natural History, all at the University of Glasgow

William Gray, jeweller in Glasgow

John Robertson Reid, cabinetmaker there

Archibald Mclellan, coachmaker there

Andrew Bannatyne, writer there

Dugald John Bannatyne, writer there

James Anderson, merchant there, son of the late Dr Anderson, Stockwell Street

William Brown, oil and colour man there

Charles Hutchison, merchant there

John Smith, youngest, bookseller there

Thomas Atkinson, junior, bookseller there

James Brach, senior, bookseller there

Robert Ferrie, builder there

James Davie, haberdasher there

James Steven, writer there

David Napier, engineer there

James Haddin, writer there

Robert Maxwell, junior, residing in Maxwelltown Place, Glasgow

George Douglas, plumber there

John Strang, wine merchant there

James Duncan of Mosesfield

Third Class:

John Graham, John Gibson, Daniel Macnee, Horatio Macculloch, Andrew Henderson, James Glen, P[eter] Paillou, JS Harvey, all painters in Glasgow

Robert Gray senior, Robert Gray, junior, Joseph Swan, Hugh Wilson, all engravers in Glasgow

Thomas Boston, John Brown, seal engravers in Glasgow

William Mossman, sculptor there

Dr Thomas Paterson, modeller there

David Hamilton, John Hamilton, John Weir, Robert Scott, John Herbertson, all architects in Glasgow

James Willis, Alexander Finlay, Daniel Chisholm, William Murray, all carvers and gilders in Glasgow.

By 1866, only John Wright and Andrew Bannatyne remained alive.

Postscript

The papers of ‘James Haldane, engraver, Glasgow, 1789-1844’, originally held by the solicitors’ firm of Bannatyne, Kirkwood, France & Co., are now included in the Business Archives Council of Scotland, held in the University of Glasgow’s Archives and Special Collections.

As for Cunningham Grahame and Haldane’s Holtzapffel lathe, by 1896 it was in Yorkshire, and by the 1950s in Cornwall. Its last known owner, now deceased, sold it during the 1990s and its current whereabouts are not known. A later Holzapffel lathe, No. 930 (above), is in storage, part of the collection of Glasgow Museums.

The farm exists today, expanded to 100 acres with the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park and specialising in Highland cattle

J G Smith, Strathendrick and its Inhabitants from Early Times, Glasgow 1896. “The problems resulting from the secession of so many members were not resolved until 1830, but even then worship continued separately in the Relief church and at Kilmaronock”: https://www.kilmaronockoldkirk.org.uk/old-kirk-history

In 1836, it merged with the Ship Bank as the Glasgow and Ship Bank, and became part of the Union Bank of Scotland in 1843

Perthshire Courier, 23 Apr 1824

Glasgow Herald, 2 Oct 1826, and 29 Sep 1826

Glasgow Herald, 6 Oct 1826, The Scotsman, 26 Apr 1828

Oxford University and City Herald, 24 May 1828

See The Society of Ornamental Turners Bulletin, 2005

Fifeshire Journal, 26 Oct 1833

Raffaello Sanzio Morghen (1758-1833) engraved works by Da Vinci, Raphael, Murillo and Van Dyck. Domenico Zampieri (1581-1641) and Guido Reni (1575-1642) were Baroque Italian painters

Birmingham Journal, 17 Oct 1846

The Scotsman, 13 Sep 1826

Perthshire Courier, 11 Jan 1827

See https://cunninghamegrahamblog.wordpress.com/tag/william-cunningham-cunninghame-graham-of-gartmore-finlaystone/ for a more extensive story

PB Ellis, The Radical Rising: The Scottish Insurrection of 1820, Gollancz 1970

The Scotsman, 26 Mar 1828

Many members of the Thomson family were buried in Blackfriars Churchyard, and it was their 1875 transfer to Craigton Cemetery in advance of the demolition of Blackfriars Church that led to the commission for a family monument from J.& G. Mossman, who did so by reworking ‘Greek’ Thomson’s 1867 monument design for the Rev. A.O. Beattie, minister of the Gordon Street U.P. Church.