Thinking of Alexander Thomson, you may recall a tousle-haired bearded man in his 40s and 50s. That you can do so reflects the number of images there are of him. But why so?

The first image we come across is a plaster bust, ‘enclosed in a clear glass case with a varnished mahogany frame and base and has a purple cotton backing on a silk padded oval stand’, currently located at Holmwood. This image, dated to the late 1840s (glasgowsculpture.com suggests 1847), shows us Thomson, aged around 30, around the time he married and about to set up in partnership with his brother-in-law, John Baird II.

The bust is by the Glasgow sculptor John Mossman (1817-1890), who would sculpt the posthumous marble bust a quarter century later.

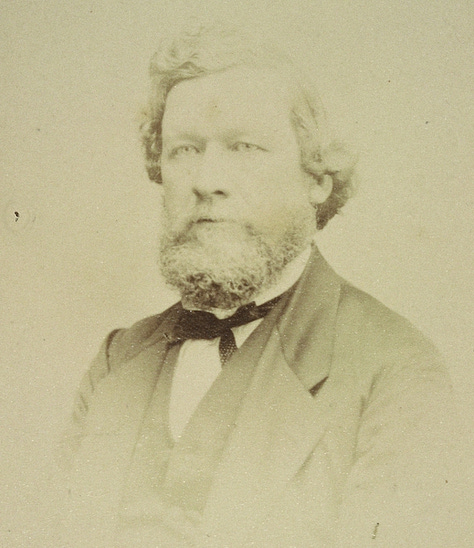

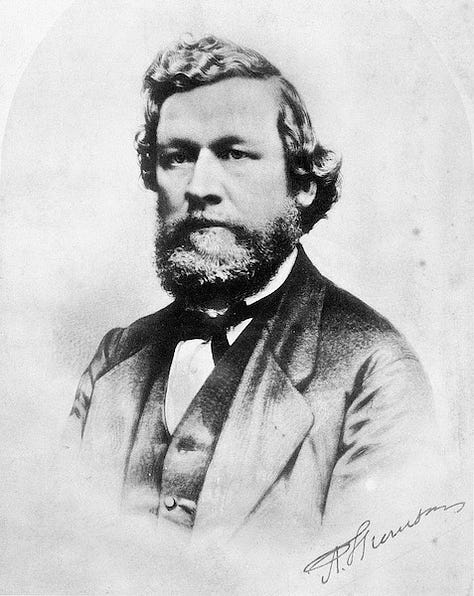

Our second image of him is photographic, still unbearded, but obviously some years after the plaster bust.

Here, his face is heavier, his hair longer. It is a studio shot that probably dates from around a decade later. If we date this to 1859, when Thomson was 42, he would have fathered eight children, four of whom, two sons and two daughters, had already died. (The marks apparent on the face would appear to be from the photograph rather than from life, especially if we take the later pastel drawing as a more accurate representation of skin tone).

The picture above certainly bears out assistant William Clunas’s later recollections. Clunas remembered him as

‘a distinguished looking man of good average height, stout, well and proportionally made, a fine manly countenance with a profuse head of hair. His general appearance was indeed, very much in harmony with the strength and elegance which he imparted to the structures he designed, while the genial smile which so often overspread his face might be fittingly compared to the finished enrichment which was so marked and pleasing a feature of his compositions’.

We have three known photographic images of Thomson, as well as two busts and a pastel drawing. Apart from the image above, the other two photographic images were for cartes de visite, which themselves were the basis of a retouched photograph and the pastel drawing. Of other well-known architects alive when photography was becoming popular, we have far fewer known images: two photographs and a drawing of John Honeyman, one of Charles Wilson and of John Baird I, none of James Smith or John Baird II. Even later architects are hardly well-represented, with two images and a drawing of Alexander’s son John, who lived until 1933. That is not to say that they were not photographed or that images are not held in archives or family collections, but none appear to be widely available.

The Glasgow Photographic Society

Thomson took a personal interest in photography. In March 1854, he was elected one of four lay (‘non-practical’, according to the Secretary) Committee members at the inaugural meeting of the Glasgow Photographic Society. The other lay members were Charles Griffin, Mr McLure and ‘Mr Watson of the School of Design’1. Charles Griffin was probably a partner in Richard Griffin & Co., publishers, booksellers, stationers and manufacturers of chemical apparatus. Their shop was in Buchanan Street. ‘Mr McLure’ could be any one of several McLures involved in James McLure & Son, carvers, gilders and printsellers, since the inaugural meeting was held in their gallery in Buchanan Street. Mr Watson was William West Watson, Treasurer of the Government School of Art and Design, and a Glasgow Fine Art Association council member, later Glasgow’s City Accountant, and City Chamberlain from 1862.

In April 1859, the Society held an exhibition in ‘the gallery of Messrs J. Little & Co.’s Crystal Palace, 67 Buchanan Street’2. Little & Co. were ironmongers, but it was also the workplace of ‘photographist’ John Werge. This was no small event, comprising 746 images, including named and unnamed persons and an array of 'views' and story photographs. While many photographs were of England (Tintern Abbey being popular), Wales and rural Scotland, there were images from the Crimea and Egypt (the latter by Francis Frith). William Church exhibited three images of Glasgow Cathedral, Duncan Brown showed images of Crookston Castle, The High Church from Mason Street, Gartsherrie House, Haggs Castle, Gilbertfield House, and others. John Cramb provided a frame of 11 stereographs of Glasgow, John Kibble images of Glasgow Harbour and of the Theatre Royal, and Alexander McNab provided more.

John Werge was from Newcastle and was initially a Daguerreotypist, He adopted the collodion process and became an assistant to Cornelius Jabez Hughes in Glasgow as a daguerreotype colourist. He took over the business when Hughes moved to London (Werge followed later). In 1880, he issued The Evolution of Photography, combining a ‘chronological record’ of photographic progress with ‘personal reminiscences extending over forty years’.

Photography became increasingly popular through the 1850s, as Werge recalled:

‘At the photographic exhibition in connection with the meeting of the British Association held in Glasgow, in 1855, I saw the largest collodion positive on glass that ever was made to my knowledge. The picture was thirty-six inches long, a view of Gourock, or some such place down the Clyde, taken by Mr. Kibble. The glass was British plate, and cost about £1. I thought it a great evidence of British pluck to attempt such a size. When I saw Mr. Kibble I told him so, and expressed an opinion that I thought it a waste of time, labour, and money not to have made a negative when he was at such work. He took the hint, and at the next photographic exhibition he showed a silver print the same size. Mr. Kibble was an undoubted enthusiast, and kept a donkey to drag his huge camera from place to place’3.

John Kibble (1815-1894) was an inventor, engineer and amateur photographer:

‘As a photographer he is best known for creating, in 1858, the world's biggest camera. It was mounted on a horse-drawn cart and had a lens with a diameter of 13 inches.

In 1865 Kibble built a large iron-framed conservatory at his home Coulport House in Cove on Loch Long. In 1871 the structure was re-erected and extended in the Botanic Gardens in Hillhead and two years later the Kibble Crystal Art Palace and Royal Conservatory was officially opened to the public’.

By the late 1850s, popularity and the number of practitioners competing to make a living from photography tended to drive down prices:

‘Only a day or two before [Cornelius Hughes] left Glasgow, he occupied the chair at a meeting of photographers, comprising Daguerreotypists and collodion workers, to consider what means could be adopted to check the downward tendency of prices even in those early days. I was present, and remember seeing a lady Daguerreotypist among the company, and she expressed her opinion quite decidedly. Efforts were made to enter into a compact to maintain good prices, but nothing came of it. Like all such bandings together, the band was quickly and easily broken’.

Apart from the 1859 exhibition, we do not hear much about the Glasgow Photographic Society. By 1862, it had been replaced by the Glasgow Photographic Association, which was active from 1862 until 1900. In February 1863, the Association held its own exhibition, which seems to have included some of the images exhibited four years earlier4. At some point (Werge does not give the date), there was a further exhibition in Glasgow, at which a fire occurred:

‘My pictures frequently appeared at the Glasgow exhibition, but at one, which was burnt down, I lost all my Daguerreotype views of Niagara Falls, Whipple’s views of the moon, and many other valuable pictures, portraits, and views, which could never be replaced’.

There may well have been images of Glasgow and well-known figures that disappeared in that fire.

Commercial photographer Archibald Robertson, at different times the Society’s Secretary, Vice-President and President, attempted to create an album of all the Society’s members. However, the album, now held by the University of Glasgow, has several missing images, and Thomson’s name does not feature.

Cartes de visite

One reason for the popularity of photography was the invention of the photographic carte de visite, patented in a 2 1/2” x 4” format in 1854 by Paris photographer André Adolphe Disderi (Werge gives the responsibility to ‘M. Ferrier, of Nice’ in 1857). So popular did the format become, partly because of its low cost - the press called it ‘cartomania’ and Queen Victoria was an avid collector - that within a short time i Glasgow one could buy ‘beautiful Paris-made Carte de Visite albums’, fortunately, ‘at last week’s prices’5.

Whether because of his own interest in photography, or simply the fashion for cartes de visite, Thomson had at least two of his own, shown below. The second, but probably the first as well, were taken by Messrs White of 98 West George Street in the 1860s. The image on the right was produced by The British Architect after Thomson’s death in 1875, and appears to be a re-touched version of the first carte.

None of the other immediate members of the Thomson family are known to have been photographed, save for John Thomson later in life, or if they have, they are now widely available.

The value of photography

Thomson himself seems to have been well aware of the utility of photography, especially in creating awareness of other cultures. In his address of 7 May 1866 to the Glasgow Architectural Society, An inquiry into the appropriateness of the Gothic style for the proposed buildings for the University of Glasgow, with some remarks upon Mr. Scott’s plans6, he stated:

‘The races of men which have developed architectural styles hitherto, have laboured within comparatively restricted spheres. But the zeal of modern delineators and photographers has enabled us to gather together examples of the achievements of all who have gone before us; so that we may sit by our firesides and quietly analyse them, marking their constituent elements, watching the gradual expansion of principles, and tracing the relation of different styles and varieties to each other. We have also the productions of the pencil and the chisel brought under our notice in the same convenient form.’

Thomson does not himself appear to have been a photographer. The folder of photographs gifted after John Thomson’s death to Glasgow Corporation in 1934 comprise ‘commercial views by Frith and others of Islamic buildings in Cairo and Seville in addition to ones of the Alhambra’, suggesting, according to Gavin Stamp in his ‘Introduction’ in The Light of Truth and Beauty, that Thomson might have gone on to look at islamic architecture in a continuation of his Haldane lectures7.

For Thomson, access to drawings and photographs was clearly necessary in order to illustrate what he was talking about:

‘Perhaps what is most remarkable about the Haldane Lectures is that he discussed the buildings of Egypt, Greece and Rome with such perspicacious intimacy and vividness, for he knew them only through prints, paintings and photographs’.

Thomson purchased images, and had others created to illustrate at least one of his Haldane Lectures:

‘Thomson’s second lecture, on Egyptian architecture, was delivered on 27th March and in the review in the Glasgow Herald three days later it was noted that it had been “copiously illustrated by large-scale drawings, made by students – some of them coloured as to show the Egyptian manner of decoration – and by a large perspective of the Hall of Karnak, painted especially for the lecture by [James] Sellars.” The drawings were executed under the direction of Robert Greenlees, headmaster of the School of Art, at the expense of the Haldane Trustees, who donated £40–50 for this; Hugh Ferguson, in Glasgow School of Art. The History (Glasgow 1995), recorded Ronald McFadzean’s recollection that lecture diagrams, including one of the Pantheon, survived in the School of Art until at least 1971’8.

A decade before, ‘drawings, photographs and other works of art’ had been on display at the Scottish Exhibition Rooms, Bath Street, when Thomson gave an address as President of the Glasgow Architectural Society in 18619.

The later images

Of the remaining two images, a coloured pastel drawing (below), in the possession of one of Thomson’s descendants, appears again to have been based on one of the 1860s cartes de visite. It may have been done during his lifetime, or shortly afterwards.

The next image we have of Thomson is posthumous, a second bust sculpted by John Mossman. Held in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum, it was unveiled 2 February 1877, just under two years after Thomson’s death, at the Corporation Galleries in Sauchiehall Street. The bust had been accepted at a meeting of the Town Council the day before, following a letter to the Council from friends who had ‘resolved that some memorial should be placed in the city which his genius did so much to adorn’. In accepting the bust, the Lord Provost made ‘graceful reference to the eminence of the late Mr Thomson as an architect’10, although the Provost did not attend the unveiling.

The following day, ‘a large meeting of subscribers… was held in the Sculpture Hall of the Corporation Galleries ... to unveil the bust of the late Mr Thomson and hand it over to the Corporation for preservation in the galleries’.

Charles Malloch, of glass merchants and glaziers Charles & John Malloch, chairman of the memorial committee, presided, with David Thomson, who had joined with Alexander Turnbull’s last partner, Robert Turnbull, in a new partnership two months before, acting as secretary.

George Thomson, Alexander’s younger brother and former business partner, was still in Africa, and it was the Revd John Stark, UP minister in Duntocher, for whom Thomson had designed his final villa, who spoke at the unveiling, stating that

‘[The subscribers] had the satisfaction of knowing that the memorial was not unworthy of their dear departed friend, and nothing he could say could add to their love and admiration and regret that a friend so dear, a comrade so genial, a professional fellow-worker so outstanding, and, above all, a genius so true and rare, intense and original, should have passed away from them for ever…’11.

Mossman’s image, with its soft hair, appears somewhat idealised, but brings out the heroic quality of Thomson’s features.

Mossman appears to have created another, previously unrecognised image of Thomson, among the statuary for St Andrew’s Hall, identified and photographed by Scott Abercrombie. Ray McKenzie in Public Sculptures of Glasgow suggests this is a speculative image of Ictinus, claimed as one of the co-architects of the Parthenon, but if so, he appears remarkably similar to Alexander Thomson; Mckenzie identifies the atlantes on the St Andrew’s Hall frontage as ‘identical in almost every detail to figures sketched by Thomson on his unexecuted competition design for the South Kensington Museum’12.

In the 1990s, sculptor Alexander ‘Sandy’ Stoddart reprised the image with his medallion (albeit reversing his image, with Thomson’s parting on the right).

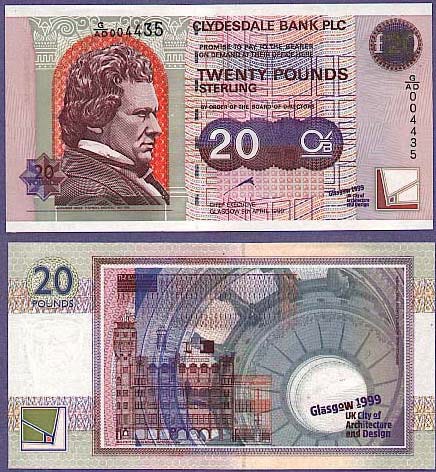

In 1999, to celebrate Glasgow’s role as UK City of architecture and design, Thomson featured on a limited edition Clydesdale Bank banknote, with Holmwood and Charles rennie Mackintosh’s Glasgow Herald building on the reverse.

More recently, The Alexander Thomson Society’s ‘Takes on Thomson’ has allowed other contributors to reflect, rework and expand on Thomson’s image, both seriously and humorously, as well as his buildings. Thus Thomson’s image continues.

Scottish Guardian, 10 Mar 1854

Glasgow Herald, 1 Apr 1859

J Werge, The Evolution of Photography, London, 1880

Glasgow Herald, 20 Feb 1863

Glasgow Courier, 23 Oct 1862

Published in full in The College Courant, the Journal of the Glasgow University Graduates Association, Vols. VI and VII, Glasgow, 1954

G Stamp (ed.), The Light of Truth and Beauty, Glasgow, 1999

ibid.

Glasgow Herald, 22 Oct 1861

North British Daily Mail, 2 Feb 1877, Glasgow Herald, 2 Feb 1877

Glasgow Herald, 3 Feb 1877

R McKenzie, Public Sculptures of Glasgow, Liverpool, 2022