This wedding photograph was taken outside the Alexandra Hotel, 148 Bath Street, Glasgow, converted from a townhouse during 1876 to designs by Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson (It seems unlikely that Thomson’s last partner, Robert Turnbull, made any significant changes to the design in the period after Thomson’s death in March 1875).

The photograph was taken by J & R Couper, ‘photo artists and flashlight experts’, based at the ‘Royal Photo Studio, 219 St Vincent Street, opposite Windsor Hotel’ between 1902 and 1913. The photograph possibly dates to after 1907, following the death that year of Thomas Edwin Cuddeford, after which the hotel licence was taken over by his widow: an earlier wedding photograph taken outside the hotel shows the words ‘T. E. Cuddeford’ above the door.

The noticeable angle of the hotel building behind the group reflects the fact of the sloping pavement outside the hotel, with the photographer concentrating on ensuring the line of the wedding guests.

Apart from the anthemion over the door, the hotel shows the distinctive Thomson railings design, presumably manufactured by the Saracen Foundry. However, the lamp posts flanking the main entrance do not appear in Macfarlane’s Castings catalogue; nor do the lamp globes match anything in the catalogue, which may mean that these were sourced from another foundry, although the basic designs of both are similar to ones by Macfarlane.

Becoming the Alexandra Hotel

Until 1874, 150 Bath Street, on the northeastern corner with West Campbell Street, was listed in the Glasgow Post Office Directory as occupied by M J Bowden, accountant. He was actually Menzies James Bowden Fullarton, sometime Secretary of the Union Bank of Scotland and at his death Convener of the County of Bute. He lived at 21 Newton Place and died there on 20th February 1876. He left an estate to his widow worth an equivalent of £1.7 million today, but she died a month later at Newton Place1. Bowden had adopted the surname Fullarton on his marriage: his wife was a member of a long-standing landowning Bute family whose ancestors had been stewards in the time of Robert Bruce2. Bath Street had been his home (and possibly office) since 1857.

The first reports of a change to the building are recorded in Building News at the end of 18753. An 1877 report in The Builder noted that the building had retained its essential plain frontage except for the upper storey where there were

pilasters and a well proportioned truss, the whole surmounted by a massive cornice... Mounting the flight of stairs from Bath-street the visitor finds himself in a handsome reception-room, lighted by two large windows of plate-glass, reaching almost from floor to roof, a height of 16 ft., and all the decorations and appointments of which are appropriate and luxurious. The coffee-room is placed at the end of the hall, the extremity of the room near Bath-street being a sort of continuous window, in front of which runs a balcony supporting evergreen plants. This room is 40 ft. in length, 28 ft. in width, and 16 ft. high.”

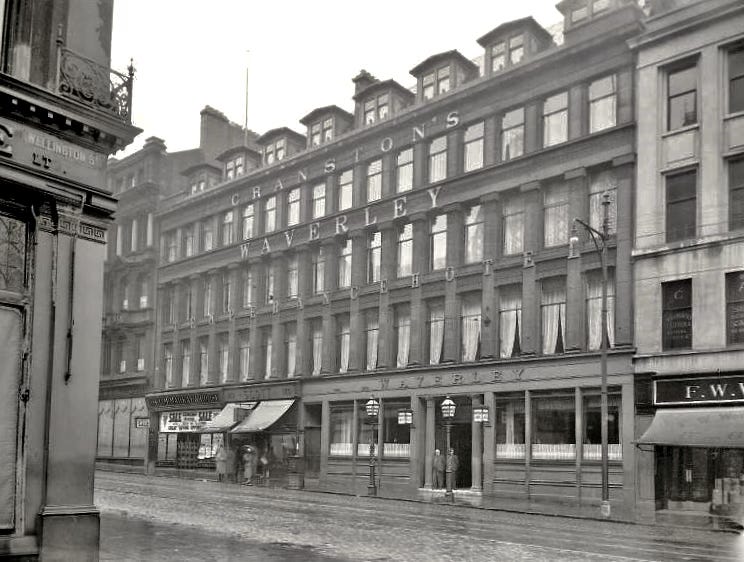

Based on the contemporary image above, Thomson added two additional floors: that comprising the heavy cornice around the southern and western sides of the building, plus attic servant’s rooms faced by what might seem an excessive amount of chimneypots. Apart from enhancing the ground floor entrance in Bath Street, the work involved incorporating a separate address at 144 West Campbell Street (Daniel Fisher, who lived there in mid-1874, had moved out by the following year). The fact that this provided a separate entrance to the hotel would later prove a bone of contention.

A pair of Macraes

The 64-room hotel must have opened by May 1877, since that month a reward was being offered for a diamond ring lost en route from Wemyss Bay to the hotel, although the hotel missed being included in that year’s Glasgow Post Office Directory. The hotel was managed by John Macrae4. Directly across West Campbell Street at No.152 Bath Street was Macrae’s Hotel, whose manager, Charles Macrae, possibly a relation and who also managed the Royal Hotel in George Square, somewhat indignantly advertised in August, cautioning

Visitors intending to put up at Macrae’s Hotel will be careful to see that they are taken there, as mistakes have occurred causing great disappointment. No connection with any other house in Bath St.

Charles Macrae had a somewhat over-positive view of the position of the hotel: while the hotel was ‘within easy distance of all the Railway Termini and Steamboat Wharfs’, claiming that in 1877 it was ‘situated in the quietest and healthiest part of Glasgow’ might be considered something of a stretch.

Licensing issues

The actual owner of the hotel at this point, and therefore the person who commissioned Thomson & Turnbull to convert the townhouse, was probably Robert Aitkenhead. In a case in front of the Glasgow licensing authorities at the end of 1877, it was stated that

In the beginning of the year [1877], Mr Aitkenhead had entered into an agreement to let to Mr Cranston the Alexandra Hotel. Thereafter the building was proceeded with, but as it was not finished in conformity with the agreement, Mr Cranston repudiated the transaction, Mr. Aitkenhead then entered into possession of his hotel and carried on as such. Wishing to have the license, he obtained an extract of the certificate and paid the money to the Excise authorities, for which he got the license5.

In his evidence, however, Stuart Cranston, older brother of Kate Cranston of tea-room fame, gave a different timing. At the end of 1874, the writers Murdoch & Rodger had commissioned Alexander Thomson to convert his existing tenement at 126-132 Sauchiehall Street into a hotel (below). It opened a week before Thomson’s death6. It was taken on by Stuart Cranston and named the Washington Temperance Hotel (later renamed the Waverley Temperance Hotel).

Cranston stated that he had

negotiated for a lease of the premises, to be used as a hotel, to commence in May, 1876, and continue for ten years. Disputes arose between Mr Aitkenhead and him as to the completion of the premises, and he had not taken possession.

However,

In April last [that is, 1877] he applied to the Magistrate for a hotel certificate, which was granted for the premises, and he afterwards got delivery of the extract. That certificate was a renewal of one previously granted in his favour [presumably a year earlier at a point when Cranston still anticipated taking possession]. He never used it, nor did he transfer it to anyone. He was aware that Mr Aitkenhead had been carrying on the hotel business at the premises stated under his name but it was without his consent either directly or indirectly.

In August 1877, William Fitzjames Barry, an officer of the Inland Revenue stated that Aitkenhead had shown him a Magistrate’s certificate for the premises at 148 and 150 Bath Street, with tobacco and retail wine, spirit and beer licenses in the name of George Cranston: ‘He stated that he was manager for Mr Cranston, who could not or would not come’. Aitkenhead was asked to take a form, have it signed by Mr Cranston and return it the next day so that the officer could get Mr Cranston to acknowledge his signature. Aitkenhead promised to do but did not return.

In September, Barry went to the hotel, where he encountered Aitkenhead, and purchased half a glass of whisky. Later that day, he bought a glass of beer and a cigar.

Before then, however, Aitkenhead and Macrae, as the hotel manager, had visited the Town Clerk’s office and then the Excise office and obtained the relevant certificate and licences. At no time did they claim to be Stuart Cranston or to represent him. Aitkenhead’s lawyer claimed any fault was down to the Excise office, which had accepted the paperwork. The court disagreed, and fined Aitkenhead £120 (almost £12,000 today).

By 1879, John Macrae was listed as the proprietor of the Alexandra Hotel. Whether Aitkenhead had sold out to him, or whether the term should be interpreted as ‘Manager’ is unknown.

A competitive neighbour

At the end of 1876, work began converting another townhouse into a hotel, again by Thomson & Turnbull. This would become the Cockburn Hotel, directly opposite the Alexandra Hotel, at the southeastern corner of Bath Street and West Campbell Street.

The building, which is estimated to cost about £20,000, will have a mansard roof surmounted by a high tower, while it also be fitted with a Steven’s hydraulic lift for the convenience of visitors7.

Like its neighbour, the 100-room Cockburn contained many Thomsonian elements, from the doorpieces to the Saracen Foundry railings. The third-floor extension (including the neighbouring building to the left) appears to be ‘Greek’ Thomson’s work, and the upper ironwork appears to be by Macfarlane as well. However, the treatment of the mansard roof might owe more to David Thomson than Alexander, since the hotel opened in mid-18788.

Managers of the Alexandra Hotel

For some years, the Post Office Directory only lists the name and address of the hotel, with no information about proprietors or managers.

John Macrae must have moved on by 1887, when Johann (John) Fritz Rupprecht took over as proprietor, with his wife supervising all the cooking and catering. By 1891, Rupprecht had moved to the North British Station Hotel in George Square; when that was taken over by the North British Railway, took ownership of the Grand Hotel. He also held the licence for the Ranfurly Hotel, Bridge of Weir, for a time. Having suffered from a weak heart for some years, he died at the Grand in November 1905 at the age of 51.

With Rupprecht’s departure, Thomas Edwin Cuddeford took over the hotel. Originally from Oxfordshire, where his father was a tailor, ten years earlier he had been a waiter, so it is unclear where his funds to purchase the hotel came from.

As with Aitkenhead, Cuddeford ran into licensing problems: in 1893, he found his licence renewal at risk following having pled guilty to a member of staff serving liquor bto two men who were neither lodgers nor travellers at 1.30 in the morning, and who disappeared afterwards. However, his licence was renewed and ‘requested to be more careful about his servants’9.

Under Cuddeford in particular, the hotel became popular with football and athletics clubs, especially for visiting teams from England and Ireland. The presence of alcohol at dinners could be problematic: when the Corinthians Football Club held their dinners at the hotel, ‘full dress being imperative’, Cuddeford was obliged to purchase ‘a special lot of unbreakable plants to adorn the table in view of the “lads o’ mettle’s” visit’10 .

It’s possible that Cuddeford stepped back from the business at one point: in 1895, a license was granted to the Alexandra Hotel in the name of David Cunningham, ‘Mr Cuddeford, the present holder, retiring on account of ill-health’11. If so, he soon returned, possibly as a result of Cunningham’s lack of attention to the licensing laws; in April 1898, Cuddeford’s application for a license was objected to by the minister of Bath Street U.P. Church ‘on account of its past history, and also on account of the existence of what was practically a public house in the side street’ (that is, access to a bar through the West Campbell Street entrance). While one member of the licensing committee accepted the problems of closing off that door and bringing ‘potatoes through the front door’, the licence was refused12.

Six months later, Cuddeford tried again:

The establishment had not paid as a temperance concern. There were five other temperance hotels in the vicinity. and it had been shown that there was no room for a sixth.

With the hotel being advertised as ‘Under New Management’ and ‘Entirely Redecorated’, this time the licence was granted on the condition that access through the West Campbell Street doorway be closed off13.

Thomas died in November 1907, although he was still listed as the proprietor in the 1908 Glasgow Post Office Directory. By 1909, his widow was listed as the proprietrix. Under her management, the hotel contributed to attract weddings and association meetings and dinners: athletics associations, footballers and harriers feature regularly in press notices of the period, as do the Glasgow Fancy Dress Association and the Glasgow Esperanto Society.

The Alexandra Hotel closed around 1916, since by April 1917 its incorporation into the expanded adjacent Pettigrew & Stephens store had been completed. The expansion, it was claimed, allowed a doubling of the size of the store’s restaurant14.

Later years

In the 1920s, the ground floor entrance from Bath Street was altered by Keppie & Henderson as part of an extension to Pettigrew & Stevens’ Sauchiehall Street premises. This involved re-facing both the Bath Street and separate West Campbell Street entrances. This work may have been undertaken at the same time as the construction of the building to the right seen in the photograph above. This was created to provide a separate entrance to menswear department:

When the store is finished, men will be as completely catered for as this firm now cater for their wives and daughters15.

The sculptor who modelled the bronze work at the entrance to the new Bath Street block was Benno Schotz. The hotel attic bedrooms may have been replaced by offices or storerooms as result of work between 1938 and 1940 or later16. In 1970, now owned by Sir Hugh Fraser, Pettigrew & Stephens relocated to a nearby smaller department store (the former Alexander Henderson’s at 171-193 Sauchiehall Street, also Fraser-owned). In 1971, initial planning approval was given to replace these buildings, together with those on Sauchiehall Street and adjacent ones occupied by Copeland & Lye, with a hotel and office development. However, the plans were ultimately rejected by Glasgow City Council claiming there wasn’t enough shopping provision and the height of the proposed buildings would block daylight17. The buildings were then demolished and replaced by the Sauchiehall Street Centre.

North British Daily Mail, 30 Mar 1876

North British Daily Mail, 22 Feb 1876

Building News, 31 Dec 1875

G Stamp, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, London, 1999

North British Daily Mail, 21 Dec 1877

Glasgow Herald, 8 Dec 1874; North British Daily Mail, 16 Mar 1875

Glasgow Herald, 25 Dec 1876

Glasgow Herald, 4 Jul 1878

Glasgow Evening Post, 20 Apr 1893

Scottish Referee, 1 Jan 1894

Glasgow Herald, 24 Apr 1895

North British Daily Mail, 29 Apr 1898

Glasgow Herald, 1 Oct 1898; North British Daily Mail, 19 Oct 1898

Daily Record, 12 Apr 1917

Glasgow Observer and Catholic Herald, 11 Jun 1921

Daily Record, 19 Mar 1971