Baird & Thomson's Jamaica Street warehouse

If you haven't heard of it, it's because it didn't happen...

In April 1853, the Glasgow Herald announced the intention to erect ‘a Large, substantial and elegant TENEMENT, suitable for a WHOLESALE and RETAIL WAREHOUSE’ on Jamaica Street, erected to suit the needs of the tenant and to be ready for occupation by Whitsunday, 18541.

The Herald advertisement noted the advantages of the location:

The site is one of the most desirable in Glasgow for the purpose to which it is to be applied. Being in the centre of a thoroughfare daily enlarging, and in close proximity to the Harbour and the Southern Railway, a Tenant of enterprise and capital will seldom find a more suitable opening for the establishment of an Extensive Business.

The architects to whom any ‘Tenant of enterprise’ should refer were Baird & Thomson, architects of 112 Hope Street.

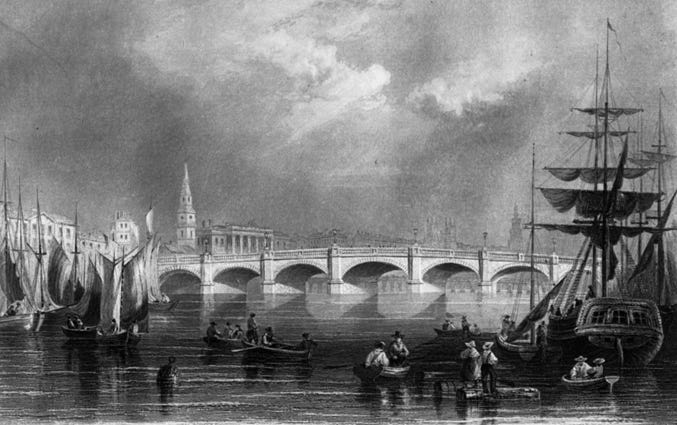

Today, Jamaica Street is hardly regarded as a premier shopping street, and in 1850, it contained a mix of small businesses, grocers, tobacconists, clothiers and tailors, often operating out of somewhat run-down premises. Towards the southern end of the street, the proximity of the Clyde supported a range of glass and iron merchants, shipping agents, as well as the Edinburgh Ropery & Sail Cloth Company at No. 76. Many of these businesses occupied tenements and workshops somewhat decayed from Jamaica Street’s origins in 1763, named when the rum and sugar trade with Jamaica and the West Indies was flourishing. By the 1850s, the street’s principal purpose was that it led to the 1833 Thomas Telford-designed Glasgow Bridge at its southern end, connecting the north of the city with Laurieston, Tradeston, the Gorbals and points south. The Bridge also marked the nearest point to which passenger and cargo shipping could approach the city, and separated Clyde Street to the east from the Broomielaw to the west.

By the 1850s, the Broomielaw was becoming more important to Glasgow as an embarkation and disembarkation point for passengers and goods. A major challenge had been that of deepening the Clyde to allow larger ships to approach. In 1768, the Birkenhead-born canal engineer John Golborne had advised the river be made narrower and the effect of tidal scouring improved by constructing rubble jetties and dredging sandbanks and shoals, and from then into the early 1800s, hundreds of jetties had been built out from the banks of the river between Dumbuck and the Broomielaw. In some cases, this had the effect of deepening the river as the increased flow of now-constrained water wore away the river bottom. In other cases, however, dredging was required: in 1850, underwater explosives were used to cut a channel in the northern half of the river to a depth of fourteen feet. This work would continue until the late 1850s.

A major stumbling block to access by larger ships to the city was the submerged Elderslie Rock near Renfrew, whose size only became apparent in 1854 when the steamship Glasgow approached from New York City. Although the ship had the maximum draught considered safe for the river at that time, the Glasgow ran aground and was holed (A more substantial project began in 1880, blasting and clearing the rock to a depth of twenty feet across much of the width of the river. Completed in 1886, some 110,000 tons of whinstone were removed, much of it used for harbour works along the Clyde).

‘A lofty range of buildings in the Greek style’

In July 1853, Glasgow’s Dean of Guild Court was presented by builders James Hay and Edward Buchanan with plans for ‘a handsome range of shops and warehouses on the west side of Jamaica Street, between Ann Street and the Broomielaw’:

The effect of the proposed erectipn will be the removal of a considerable extent of old ruinous property, hitherto occupied by small public-houses, barbers’ shops, shooting saloon, and oyster-houses, and the construction of a lofty range of buildings in the Greek style, from plans by Messrs. Baird and Thomson, architects, which will improve still more the appearance of the old street….2

Not that the street was entirely rundown: the advertisement noted that Jamaica Street had improved with the opening of ‘Messrs. Arnott and Cannock’s establishment’: this was ‘Arnott, Cannock, & Co., general warehousemen, 19 Jamaica Street’, which had opened in April 1850, initially renting a warehouse from the City of Glasgow Bank. Fife-born John Arnott (1814-1898) had moved to Cork by 1837, gradually opening drapery stores in Belfast, Cork and Dublin. The partnership with Cannock (who appears to have stayed in the background throughout) ended in 1860, with the business reconstituted as Arnott & Co., under John Arnott’s half-brother Thomas Leburn Arnott. By 1872, it was one of the largest retail businesses in Glasgow, selling shawls, parasols, carpets and haberdashery. John Arnott, primarily based in Cork throughout (although for the opening of his first mainland store living in Pollokshields), developed interests in railways, shipping and horse breeding. He was knighted in 1859 for his public services in Ireland and became an Irish baronet in 1896 (The company, which later included outlets in Hull and Newcastle, was acquired by Fraser, Sons & Co. Ltd in 1936 and merged with the Glasgow drapery firm of Robert Simpson & Sons Ltd two years later).

A street of modern warehouses

Baird & Thomson’s involvement in the proposed warehouse at 72 Jamaica Street did not last long; by the following year, Scottish architect William Spence (1806-1883) was in charge. It is unclear why Spence was selected: his previous architectural work had focused on theatres (including the Theatre Royal in Dunlop Street) and churches: much of his future work would centre on Helensburgh, where he built a house for himself, but his later involvement in retail developments would include John McIntyre’s warehouse (soon taken over by W & G Millar) at the corner of High Street and Gallowgate in 1856, Arthur & Fraser’s warehouse at 14 Buchanan Street in 1873, and Stuart & Macdonald’s warehouse at 21-31 Buchanan Street in 1866 and 1879.

Spence’s design was probably radically different from anything Baird & Thomson might have proposed, a mix of masonry and cast iron building reflecting an emerging trend in Glasgow warehouse architecture, beginning with Wylie & Lochhead’s Argyle Street store of 1850 and their 1853-4 store at 37 Buchanan Street (originally Kemp’s, and extended by Boucher & Cousland later). In fact, Jamaica Street appeared to be the centre of innovative architecture for retail and warehouse purposes: in May 1854, The Commonwealth advertised The Colosseum in Jamaica Street as ‘First-Class Shops and Warehouses’ in ‘this magnificent building… for large Drapery, Clothing, Hatting, Upholstery, Ironmongery, or other concerns for which extensive and attractive premises in a leading thoroughfare are essential’.3

The Colosseum was not just intended as a retail space since

the spacious Hall, which forms part of the Building, is, during a great portion of the year, to be occupied as a Fine Art Gallery on a scale hitherto unapproached in this city, under the auspices of the Committee of Gentlemen who last season so successfully conducted the Exhibition of the Works of Modern Artists in St. Enoch’s Hall, and that, during the rest of the year, it is designed for Bazaars, Public Meetings, Assemblies, Soirees, &c.

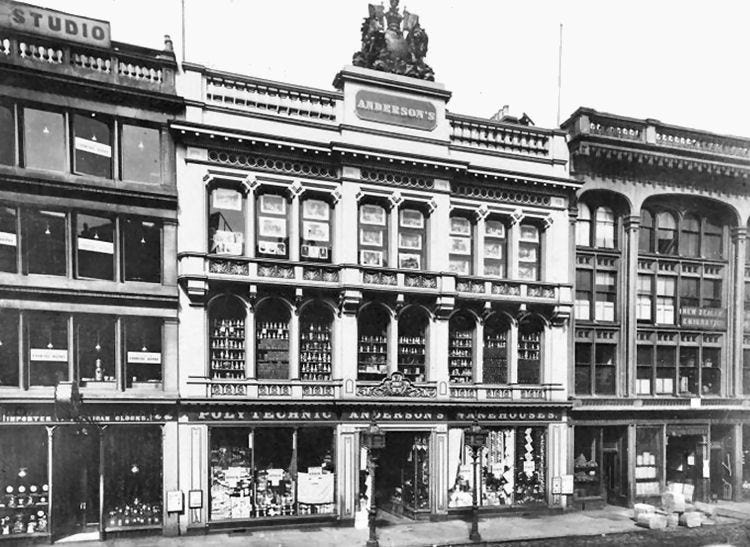

Two years later, John Anderson took on the lease; in 1837, he had opened Glasgow’s first department store in Clyde Terrace. As the Royal Polytechnic Warehouse, he ultimately employed 275 men and women, selling drapery, small wares, fancy goods and haberdashery, with four galleries in the floors above.

By 1855, John Baird I’s innovative furniture warehouse at No. 36 was in the course of erection, so that the western side of Jamaica Street ultimately displayed a range of modern warehouses, described by the late Gavin Stamp at the time of their demolition, as

the most handsome and interesting of the city centre’s cast-iron buildings…. Glasgow's collection of cast-iron buildings was unique in Britain, symbolic of the city’s remarkable industrial strength in the mid-nineteenth century.

‘Symptoms of insecurity’

Despite its simpler and presumably cheaper design, Hay & Buchanan, Spence’s builders faced problems: in early 1854, while under construction, the Procurator Fiscal complained that

the new building… had shown symptoms of insecurity. It appeared from a report by Mr. William Broom, builder, that the gables had sunk a little, and by that means one of the stone butts had fractured and the iron lintels over the shop had been broken.

However, Broom went on to say that

the building had been constructed in a most substantial manner, and that when the new beams and iron supports, which are being put up under the inspection of Mr. Spence, the architect, are completed, the structure will be most secure and substantial4.

The ‘symptoms of insecurity’ extended to the builders themselves: Hay & Buchanan owned the site, and both partners were masons, but it is possible that Baird & Thomson over-estimated the pair’s stoneworking capacity and their financial resources: Buchanan had worked on his own account for four years as a mason before becoming bankrupt in 1852, but managed to make an arrangement with his creditors and had enough resources to contribute £160 to the new company’s capital (his partner, James Hay, contributed £140).

By 1857, the new warehouse might have been completed but it remained unoccupied. That year Hay and Buchanan’s partnership was dissolved, with Buchanan continuing the business on his own account and promising to pay any debts due5. However, Buchanan failed to do so, and went bankrupt again; as a result, James Hay, still operating as a builder, was sequestrated three years later, with debts of £1,450 and assets of £406. Not until mid-1863 was the warehouse occupied, by Joseph McCrossan, a clock manufacturer and importer of American, French, and German clocks7, who relocated from 63-65 Stockwell Street. It seems likely that the Great Western Cooking Depot, the City Club & Reading Rooms and photographer Andrew Bowman occupied the upper floors/ At the end of 1865, a fire in a building at the rear of the premises may have caused some damage, although McCrossan continued to trade at No. 72, but had moved out to St Enoch Square by 1879.

Three years before, in 1876, Peter Paisley, of the S.S. Clothing Co., living at 373 Govan Street, made his first appearance in the Glasgow Post Office Directory. By 1878 he was living in the Alexander Thomson-designed tenement at 28 Norfolk Street, close to Gorbals Cross. Two years later he began operating on his own account at the vacant 72 Jamaica Street warehouse, but within five years had moved next door to occupy Nos 82-96. By 1904, the store had extended to incorporate Alexander Skirving’s warehouse at 2-12 Broomielaw, then went backwards to include Peter Paisley’s original premises at No. 72 (below).

Today, only the red sandstone MacSorley’s Bar at the corner of Ann Street and Jamaica Street remains of the Victorian blocks that once lined this part of the west side of Jamaica Street.

Glasgow Herald, 18 Apr 1853

Glasgow Herald, 12 July 1853

The Commonwealth, 13 May 1854

Glasgow Herald, 3 March 1854

North British Daily Mail, 28 Sep 1857

Glasgow Courier, 24 May 1860; Glasgow Herald, 27 Jun 1860

Glasgow Post Office Directory, 1863-1864

Hi Dominic,

Thanks for a fascinating article. I'm writing a biography of John Arnott, and noticed that you have him living in Pollokshields while he was in Glasgow. Would you possibly be able to give me the source for this, and any other relevant detail? Very many thanks. Henry. henrymacrory@gmail.com