The architect and the poisoner? (2)

Glasgow's western expansion, and the problems that came with it

Francis Garden’s youngest son, Hamilton William Garden, like others, saw the potential for profiting from Glasgow’s rapid expansion: the Town Council had extended its boundaries west of Buchanan Street to the River Kelvin. Much of this was owned by the Campbells of Blythswood, including the 35 acres of Blythswood Hill One issue for the Campbells was that when James Campbell, the then laird, died in 1773 ‘leaving no Real or Personal Estate whatever, after Sick-Bed and Funeral charges were defrayed’, his property was all either entailed or held inalienably for the family. Only from 1792 did funds start to become available to pay his creditors, when James’s trustees applied on behalf of his son Colonel James Campbell, for private legislation to break the entail and sell parts of the estate for building. This covered the Blythswood estates in Lanarkshire, and land in Cowcaddens, and Woodside. But Colonel James died in the capture of Martinique in 1794 so the estates went to his brother, Major Archibald.

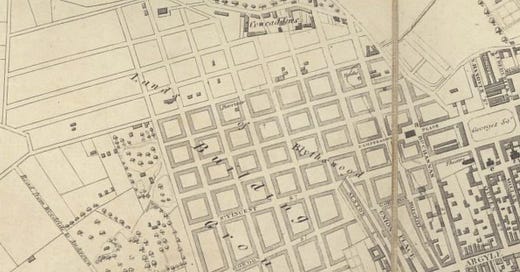

The map above shows Glasgow in 1820 and the eastern part of the Blythswood estate. The future Garnethill is the empty plots above the grey shaded blocks (which indicate projected buildings only); the treed area to the left is the Willowbank estate.

The first person to feu land from Major Archibald was James Thomson, a mason, who feued land in Woodside, but Benjamin Barton, the Commissary Clerk of Glasgow, responsible for registering wills, James Towers, founders of Glasgow’s first maternity hospital, and Dr James Cleland, now commemorated in the Cleland Memorial building by David Hamilton at the corner of Sauchiehall and Buchanan Streets. By 1807, there were 150 feuars paying Major Archibald £2,300 a year in feu duties (around £230,000 today).

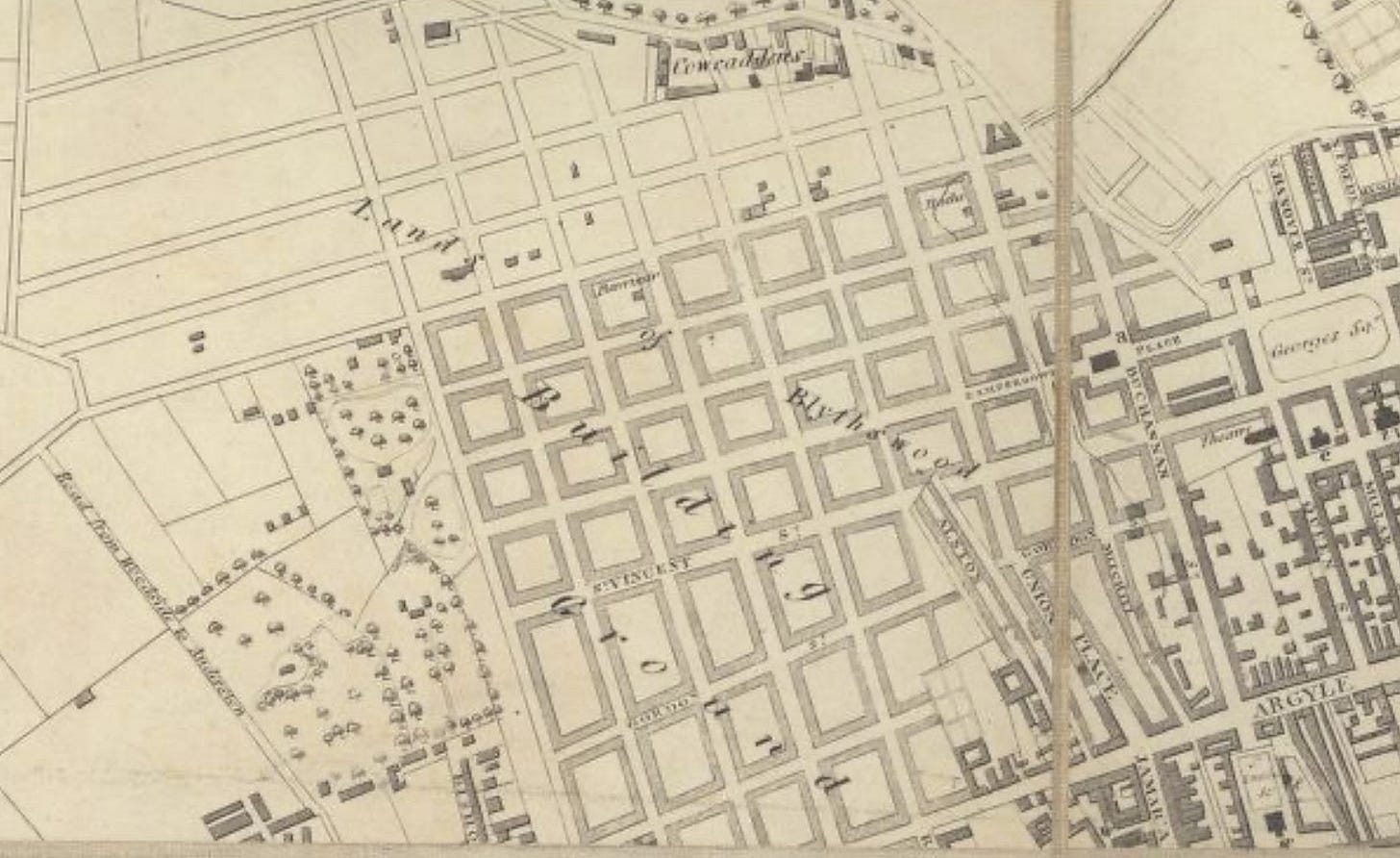

The initial developer of Blythswood was William Harley, another manufacturer involved in the Turkey Red trade. By 1804 he had purchased Sauchy Hall, located between what became Douglas and Pitt Streets on the southern side of Sauchiehall Road, which he renamed Willowbank (above). The house was later described as comprising eight apartments and kitchen, plus cellars and stables, a hothouse, greenhouse, a garden with an excellent supply of water, a bowling green and a three-acre orchard with fruit trees, gooseberry and currant bushes.

Sauchy Hall had been built by Lawrence Phillips, who operated a calico printworks in Anderston. Another businessman-turned-developer, he was among the first to feu land from the Campbells, feuing and letting out what became Garnethill for grazing cattle, as well as land in Woodside Road and St George’s Road. He built Dundasvale House (where the Dundasvale estate in Cowcaddens now sits) and various other dwellings, all of which were later levelled and replaced.

Harley, taking over Phillips’ properties, reduced the height of Blythswood Hill by about 30 feet to allow for what he intended as an elegant new square designed by James Gillespie Graham, who was also the Campbells’ architect. Locally named ‘Harley’s Hill’ it had ‘flower gardens… surrounded by a magnificent hawthorn hedge. In the centre stood a summer house mounted by a pagoda-shaped tower, 30 feet high [known as Harley’s Folly], commanding a view of the city, the vale of Clyde and the surrounding country that could scarcely be equalled in Europe’. The tower can be seen in this image to the right of the smokestack.

Harley reputedly also named Garnethill, after Thomas Garnett, late Professor of Natural Philosophy at Anderson’s Institution. The site of the future ABC cinemas on Sauchiehall Street (opposite Willowbank), was marked up as ‘Garnett Place’ on an 1807 map. On Garnethill an observatory was constructed, seen here in the middle of the enlarged image. While it was being built, Harley, who was a member of an early Glasgow astronomical society, offered his Blythswood summerhouse as a temporary observatory.

Harley developed multiple business interests. Where Phillips took water from the stream on his estate to supply his calico works, Harley initially sold it in the city from horse-drawn carts, then constructed a pipeline underneath what is now Sauchiehall Lane to a cistern near what is now West Nile Street. In 1804 he opened the first indoor public baths in Scotland, with four pools (hence Bath Street, named that by 1810). He supplied fresh milk from cows on a farm at Sighthill, supplied strawberries and other fruit from Garnethill, and promoted the agricultural use of liquid manure.

By 1816, however, he was insolvent, arising from the economic slump in Europe following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. His Blythswood properties were not yet built and he still had to pay feu duties to the Campbells.

So Harley’s properties were put in the hands of six trustees (including himself). Initially, they were able to pay a third of what was owed. In 1820 they attempted to sell off the whole of the Blythswood Square development, without success. Then, in 1821, two of the trustees were themselves sequestrated. Harley followed in 1822. His assets included:

a ‘large quantity of dung’ from the cattle at Sighthill;

‘Blythswood Square, together with the bowling green, orchards and gardens adjoining, houses and other erections thereon’ (so presumably including WIllowbank).

Plots of land on Garnethill, three steadings and a house on Bath Street and four steadings on either side of George Street. There was Enoch Bank, an ageing mansion house that Harley had purchased in 1813 and where he lived. Owning it had cost him: he had to change his boundary lines to align with the city’s planned grid pattern, seen here, to pay to open up Nile Street, and in doing so to cover the St Enoch Burn that flowed through the property down to the Clyde.

Even further west, at Kelvinside

Beyond Glasgow, Dr Thomas Lithan, who had amassed a £50,000 fortune largely from opium trading, purchased the estate of Kelvinside in 1787 and died twenty years later, his estate passing to his widow. Ten years later, she married Archibald Cuthill, a member of the Faculty of Procurators (in the process, Cuthill was obliged to adopt ‘Lithan’ as a middle name).

In 1822, Cuthill was one of Harley’s remaining solvent trustees, together with James Cook, the Glasgow civil engineer Harley had used to lay out his plans for Blythswood. Glasgow accountant Henry Paul was brought on board as a professional trustee but not technically liable for any money owed by the trust. When banker John Thomson moved to Edinburgh, Paul purchased Northwoodside from him. Harley’s trustees still owed the Royal Bank over £3,000, but Major Archibald was doing well: his feu duties were now £7,700 a year, three times what they had been before.

The deadline to pay off any claims against Harley was December 1822. In July, the trustees agreed to sell ‘certain trust subjects’ to Hamilton William Garden for £17,000, £8,000 of which comprised ‘houses to be built by Mr Garden upon part of the ground purchased by him, which houses were to be transferred to them at a valuation’. In addition, Garden provided a bond for £3,000. The trustees seem to have sold Enoch Bank to Garden separately for just over £1,150. Since Garden didn’t have cash, to cover this and other expenses he provided a second bond for £1,927 and a penny.

In a later court case, it transpired that Cuthill, Cook, and Paul had all made loans to the trust to stop Harley’s remaining assets being seized while Blythswood Square was underway: ‘Cook had advanced £17,000 out of his own funds - Cuthill upwards of £6,000 - and Paul, who was under no obligation to advance anything, upwards of £2,000.’ You have to multiply these figures by at least ten to get modern equivalents. But by the time all Harley’s original creditors had been paid off, the trust still owed £36,811 (around £3 million today), presumably a mix of building fees and feu duty.

If Cook and Paul had the money, Cuthill didn’t; to obtain it, he had mortgaged Kelvinside, advertised for someone to lease 26 acres of the estate for sheep farming, and probably more besides: six years later, the sale of a property in Stirlingshire was stopped because Cuthill had issued a bond against it.

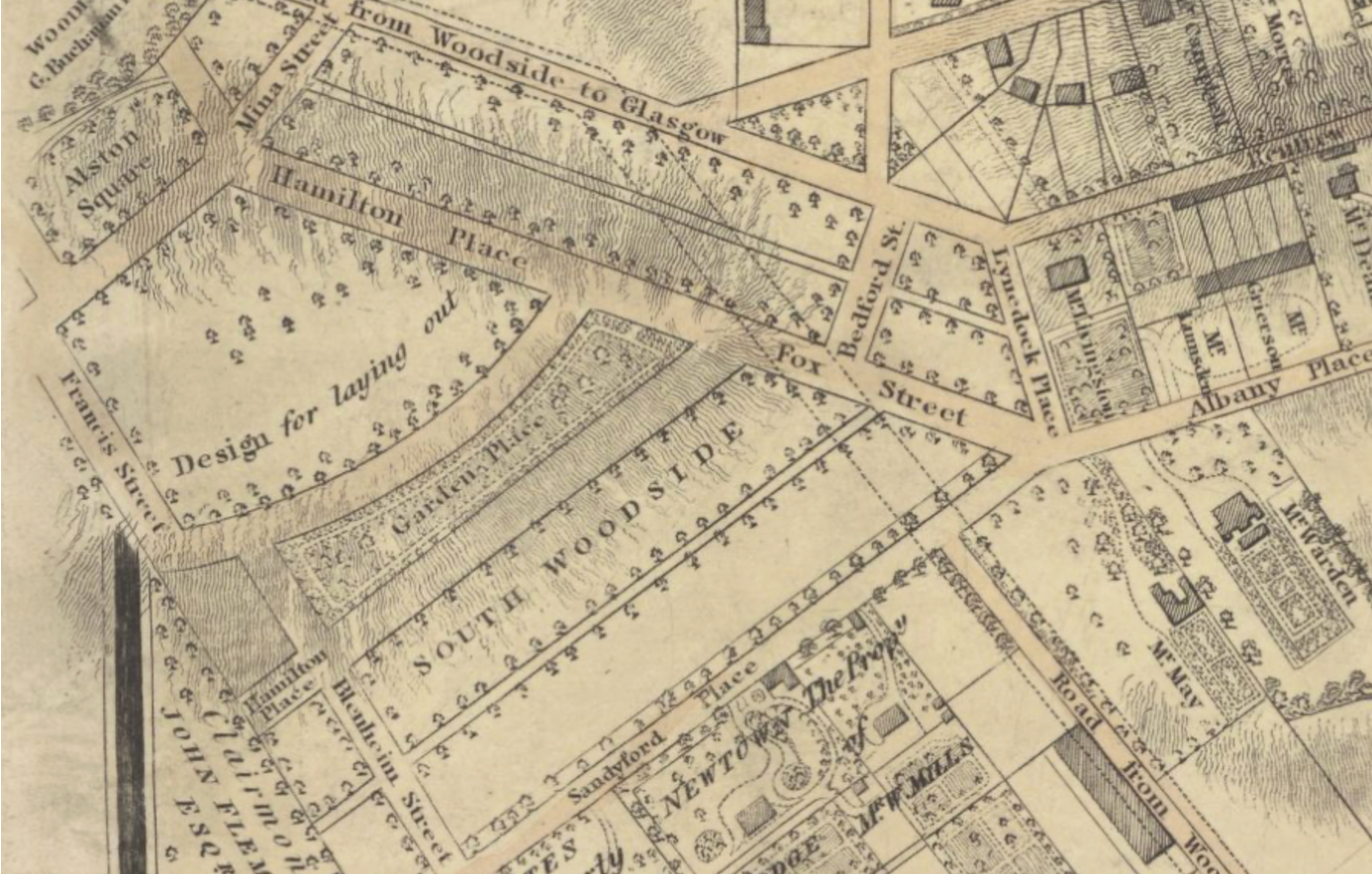

In 1825, Hamilton William Garden purchased Southwoodside, a triangle of land west of Charing Cross, now the site of Woodside Place, Crescent, and Terrace, and Lynedoch Street, Crescent, and Terrace.

The 1828 map above shows fields and copses marked off as Francis Street, Mina Street, Hamilton Place, Garden Place, and Alston Square, all named for Garden’s family and himself.

Garden now decided to acquire a country estate. On 30 January 1826, he purchased the lands of Finnick-Malice in Stirlingshire (just below the centre of the map above) for £13,550 from a purchaser who had paid more than a £1,000 less that same morning. The following month, days after the birth of his second son, ‘Hamilton William Garden, builder in Glasgow’ was sequestrated.

Garden fled to America, accompanied then or later by his wife and family. A brother, Robert, also named in the sequestration, continued in business, as agent for the Scottish Union Insurance Company, and died in Glasgow in 1840.

In May 1826, John Smith became a trustee for Hamilton William Garden’s affairs (there was at least one other trustee). The Royal Bank might have been one of Garden’s principal creditors; with luck, the Commercial Bank of Edinburgh was not: its secretary and later manager was Robert Paul, brother to trustee Henry.

Having a trustee with building knowledge would be useful in realising what value could be raised from Garden’s estate. In October, Smith was advertising shops and tenements for sale in Renfield Street with an adjacent one cornering George Street, which might have formed part of Garden’s holdings. In 1829, he sold the Finnick-Malice estate.

In America, where Hamilton William Garden seems to have changed his forenames, his wife gave birth to a second daughter. In 1845, he was finally discharged as a bankrupt; he died three years later in 1848.

In Glasgow, Cuthill, Cook and Paul, as Harley’s trustees, were paying out their own money to pay debts, feus, their architect (John Brash, who had taken over Gillespie Graham’s plans) and their builders, presumably in the hope of completing the Blythswood project, which was now dependent on Garden’s trustees, and the ‘houses to be built by Mr Garden upon part of the ground purchased by him, which houses were to be transferred to them at a valuation’.

In late 1824 or early 1825, Cuthill had changed his partner in his law business based at 21 Miller Street. With Garden bankrupt, in March 1826, his new partnership was terminated, with Henry Paul and Cook as witnesses and Paul responsible for dealing with creditors. Had Cuthill’s professional and financial credit run out? Whatever the reason, Cuthill clung on.

By mid-1828, ten out of a planned 26 houses in the square were occupied, which is when Blythswood Square first appears in the Post Office Directory. By mid-1829, as seen above, at least 20 out of 26 were occupied. But they had probably been sold off at a loss.

In February 1829, four days after winning a case which said he did not have to pay his share of a £500 bond he had guaranteed fifteen years before, Cuthill was sequestrated. He fled to France, leaving his wife destitute, to be bailed out by her brothers. They took over running of the Kelvinside estate and Cuthill died in France in 1853 at the age of ninety.