A previous article looked at the background to the creation of public urinals in Glasgow and elsewhere and considered the extent of Alexander Thomson’s involvement: possible, in the case of Macfarlane and the Saracen Foundry, likely in the case of the Sun and Elmbank Foundries. The relationship is unclear: the urinal now sited adjacent to the SS Great Britain in Bristol (above) is not by Macfarlane but repeats Thomsonesque ornamentation that does appear in Macfarlane’s Castings, such as the palmette device below.

Were these designs licensed by Macfarlane or provided by Thomson in slightly amended form to other foundries? Given Macfarlane’s litigious nature (against the Oak Foundry, for example), it is unlikely either of the other foundries simply stole them.

Macfarlane’s urinals began with single-stall enclosures and expanded to freestanding ones for eight or more men. Similar designs were used for water closets, although none of these are known to remain. In Glasgow and elsewhere, these were usually sited within easy reach (as it were) of public houses; the same appears to be true for many later public conveniences, including those constructed underground, as in Glasgow at St Vincent Place and Charing Cross, and those at New Cross Gate in London, for which a Thomson-designed ventilation shaft-cum-gaslamp was ordered.

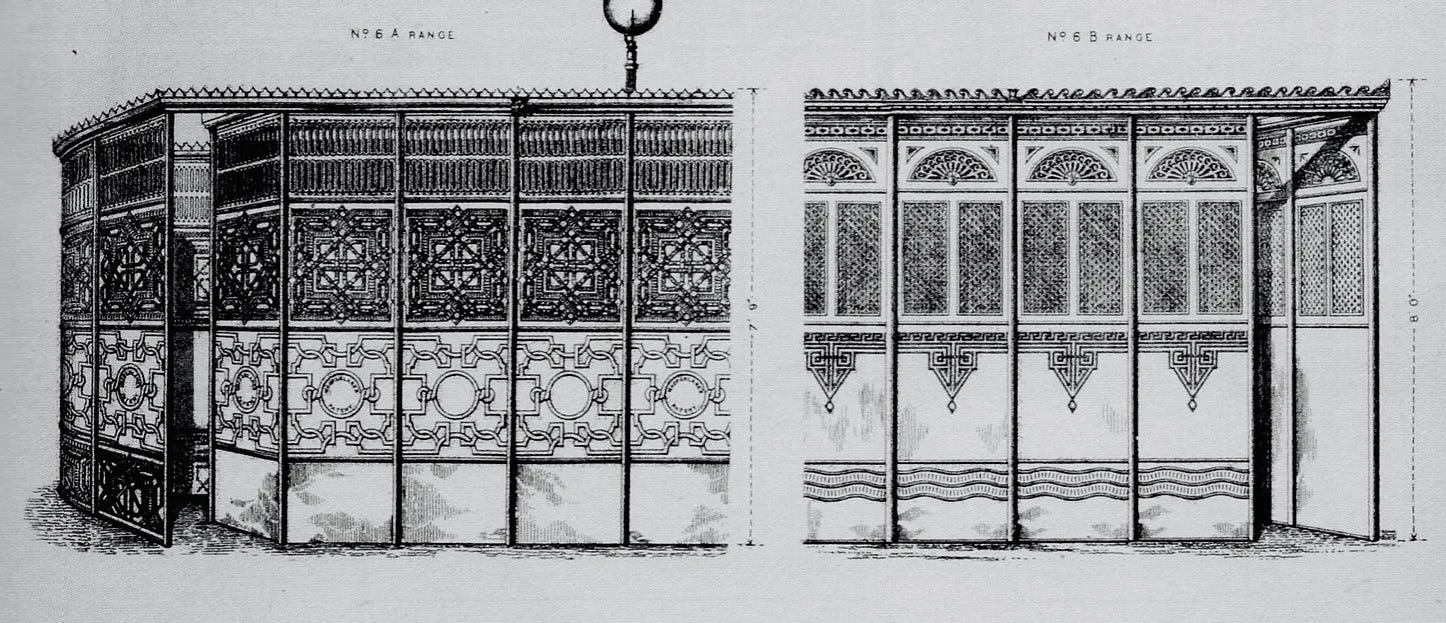

As seen above, the Saracen Foundry offered structures in a variety of panel designs, whether solid or ventilated, which could be mixed and matched according to taste (Working out which designs were used where might be a valid subject for a dissertation). Thus, it is difficult to work out which designer was responsible for what, although the Thomsonian ‘dropped finial’, as seen in the lower panel in 6B above, appears to be exclusive to Macfarlane. Some were available with external illumination by gas lamp, some used glass roofing, and others were open to the elements.

Many urinals, of course, have disappeared over time, but further research has identified that more remain; some are in use and even listed as Grade II, but many are not.

In Great Ayton, the Post Office Red structure (presumably not its original colours), is the last of three, while the Grade II Livery Road urinal is situated under the Snow Hill railway arch, and has been closed off since at least 2014.

Another Grade II structure (above) was relocated in 1903 to Black Boy Hill, Whiteladies Road, Birmingham (both the hill and the road seem to take their names from public houses). When listed, English Heritage described it as

a rectangular cast-iron structure with square entrance screens to both (north and south) entrances. It is constructed of a slender iron frame with decorative panels that are on a geometric, Moorish-style theme. The upper panels have ventilation slits. The upper iron frame has a saw-tooth detail. The hipped roof is a glazed cast-iron structure built in two tiers.

According to a newspaper report at the time of listing, although the floor tiles are modern,

the outhouse impressed English Heritage because of its “two rows of bowed porcelain urinal units with curved metal ‘modesty’ screens between them at chest level”.

Back in Birmingham, a smaller structure remains (below), but in an unloved condition, at the corner of Great Barr and Liverpool Streets. The second appears to reflect its current state (judging by other images, the Council tends to paint over new graffiti as it is applied, but not otherwise to protect or conserve the structure).

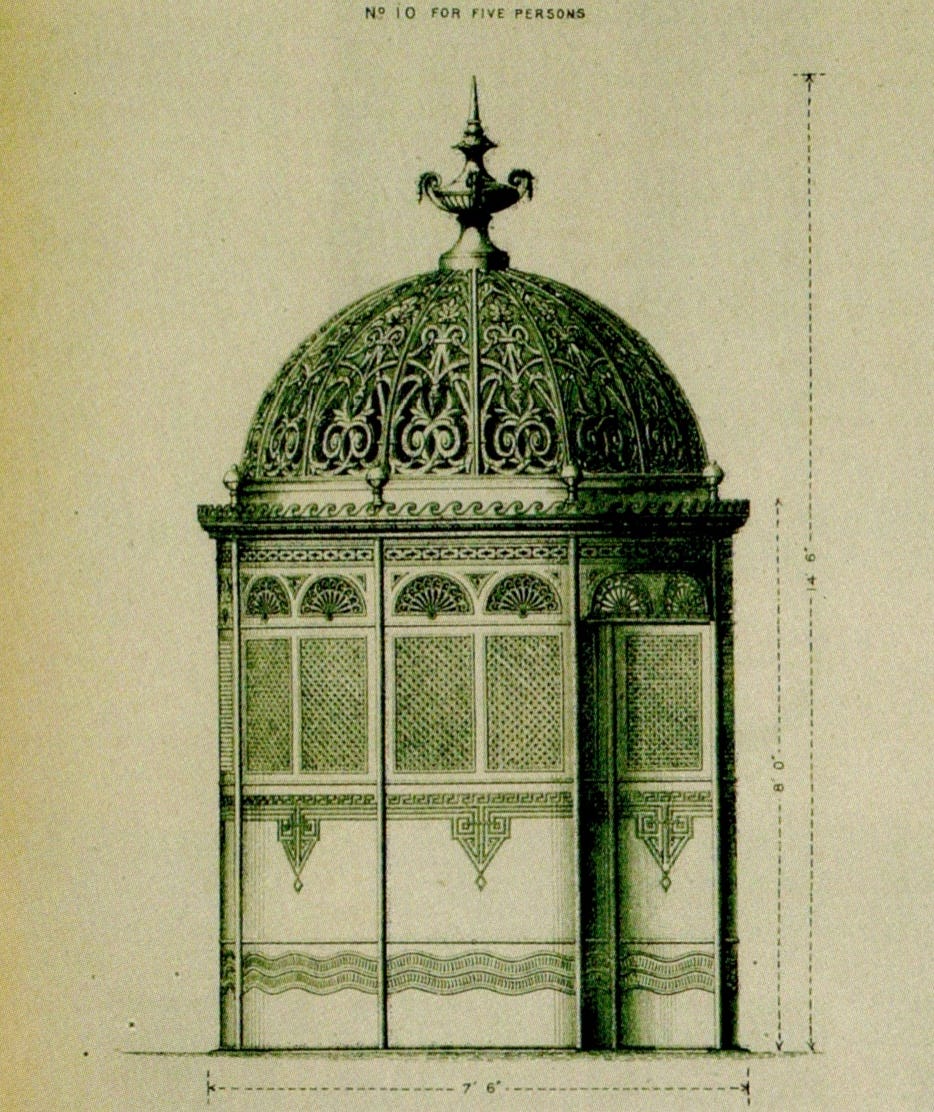

A circular Macfarlane design with a domed, pierced roof can be found on Horsfield Common in Bristol, with another at an unnamed location.

As seen above, the design in Macfarlane’s Castings uses the ‘dropped finial’ design for one of the lower panels but was not used for the structures as ordered. Both appear to have been repainted within the last few years, although the Horsfield Common one is closed off.

Meanwhile, in Europe…

As mentioned in a previous article, the earliest public urinals (in the sense of being structures put in place by local authorities for general use) were found in Paris in 1830, with the earliest Glasgow examples dating from twenty years later.

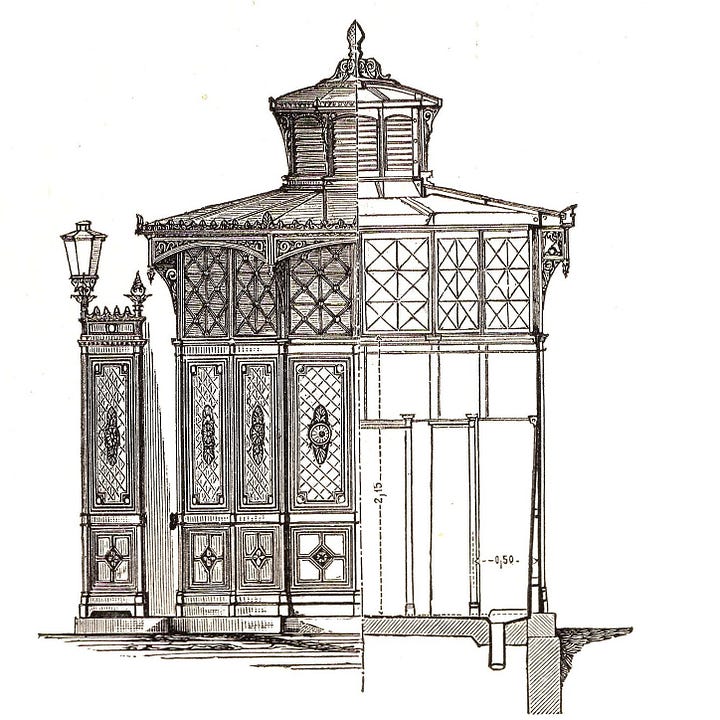

In 1878, in the German capital of Berlin, city councillor Carl Theodor Rospatt designed an eight-sided urinal to be erected across the city, presumably to improve on a design by Berlin’s police chief from a few years before. Given the dating, it seems quite possible that Rospatt’s design draws on models found in Great Britain by Glasgow foundries.

Each ‘Café Achteck’, (‘Café Octagon’) as they came to be called, had seven urinals, with the eighth wall as a door, with what appear to be marble panels for some features. Installed over the next twenty years, some dozen specimens remain of the 142 original structures, many in use as designed.

In a larger version of the building, mixing urinals with water closets, the interior appears somewhat roomier than expected.

As usual, women came second. In London, the first women’s public conveniences appeared at Piccadilly Circus in London in 1889. Only in 1900 did Berlin follow suit.

Model options

And for anyone involved in designing model train layouts, or possibly just as a desk accessory, Wills 00 Design Series SS10 Victorian Gents Toilet is available for a small sum. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to incorporate any observable Thomsonian design features.

Images

The images in this article come from various sources: Berlin interior: Architectural Digest; Berlin exterior: Pinterest - Carl Harris; Birmingham Balsall Heath: Birmingham Mail; Birmingham Great Barr Street, older: Walking for Heritage; Birmingham Great Barr Street, newer: Birmingham Mail; Birmingham Livery Street: Google 2018; Bristol Horfield Common: Geograph 2335428 by Colin Adamson; Bristol Whiteladies Road: Jon Millngton, English Heritage; Great Ayton Yorkshire: Geograph 3610921 by John M; Twickenham, York House Gardens: Londonist.com; Unlocated Circular No. 10: Pinterest - Josiah Cuffley-Thorne.