'Greek' Thomson's architectural acquaintances: Thomas and James Kennedy

Involving bicycles and the Beatles

Perhaps there was some falling out between the sons after their father’s death, because after 1877 Thomas was based at Greenock, at 25 West Stewart Street, where he now gave his profession as ‘Architect’. He remained there, working from various addresses, until at least 1889, by which time he was now an ‘architect, measurer, property surveyor, and valuator’.

A year after his father’s death, Thomas had married: a first daughter and a son were born in Glasgow; two more daughters were born in Greenock. Very little is known of Thomas’ work in Greenock: when Ladyburn mansion house at Bogston, west of Port Glasgow, was demolished in mid-1884, presumably to allow for the creation of the Ladyburn Shipyard and Repair Quay, Thomas was charged with selling off the estate trees, but another firm got the job of actual demolition and selling off the building materials, as seen below.

Thomas’ name crops up again in the case of a dispute in neighbours, persumably in the less salubrious area of West Blackhall Street, where he and his family were living in 1887: according to a press report, when the sister of a neighbour felt unwell, the neighbour went to the Kennedy’s asking ‘the man of the house to go for the doctor. The door was slammed in her face, Mr Kennedy saying at the same time he would doctor her sister’. In response, the neighbour broke a window overlooking a balcony, and Kennedy locked her there ‘for a considerable time’; ‘The charges were found not proven’.

The only architectural work Thomas is known to have been involved with was Finnart Cottage, Kilmun, in 1889, for which he ‘prepared plans, specifications, and schedules’, while supervising alterations on behalf of Robert L Alston, the feuar,. Alston, however, claimed ‘want of professional skill… gross dereliction and want of duty’ on Kennedy’s part, and held back £25 of his fee. In the end, ‘no want of professional skill’ was established, but Kennedy’s claim only resulted in £15 9s with expenses.

After their father died in late 1870, James continued with the architectural business as Angus Kennedy & Son; by the following year, he had gone into partnership with Andrew Myles, his father’s chief assistant. A month after Angus Kennedy’s death, Myles represented the firm over a valuation of a property at 24 Spoutmouth in a claim for compensation from the City Improvement Trust.

In 1866, Myles was President of the Glasgow Architectural (Assistants’) Association, but he had other interests: earlier, he had been Secretary of the St Vincent Street U.P. Church Literary Association and he would become President of the Glasgow Choral Union in 1883.

Myles’ association with James Kennedy lasted until January 1875, when the partnership was dissolved and Myles moved in early February to 121 Wellington Street, opposite A & G Thomson’s office. A month before, he and James had both become members of the Glasgow Institute of Architects. In 1876 he was the architect of the Dalmuir UP church (known as Clydebank Union Mission Station at the time), and may have constructed a ‘Superior Villa’ in Pollokshields. Later his office moved to 143 West Regent Street. He married late, but his large practice and overwork are thought to have contributed to his death, in Wester Kames, Bute, in December 1905.

Sewing machines, bicycles and the Beatles

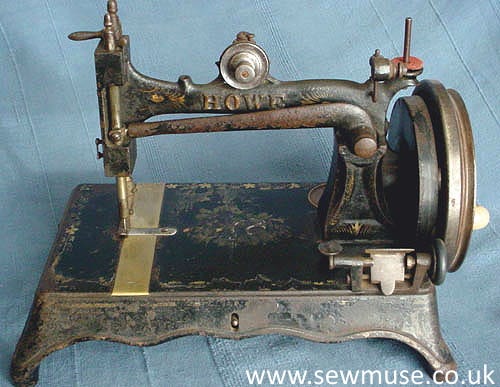

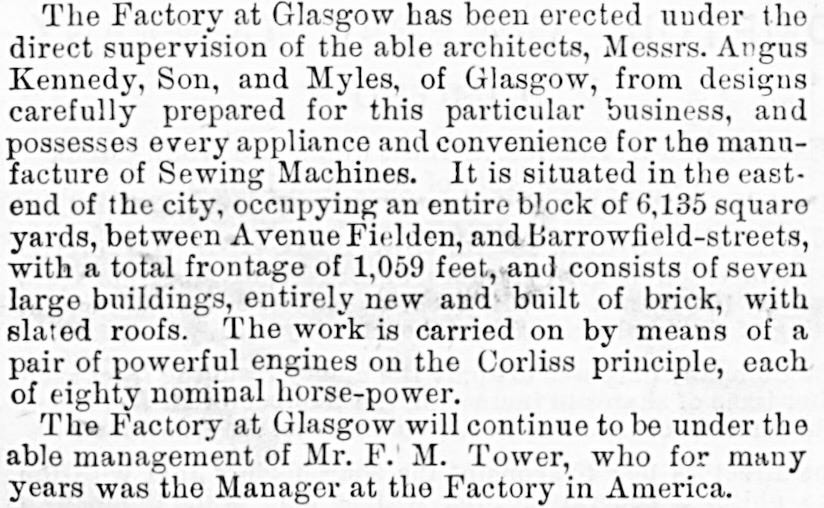

A major project for James Kennedy and Andrew Myles was the Bridgeton factory of the Howe Machine Company. Elias Howe, junior, is credited as the inventor of the modern sewing machine in the USA, but the business was expanded internationally by his older brother, Amasa Bemis Howe. Amasa took out patents to improve Elias’s invention, exhibiting sewing machines on a stand at the 1862 London Exhibition, and being awarded a prize medal for the Howe Sewing Machine Company’s machines and four medals for the excellence of work carried out on them.

In 1864, Amasa licensed their manufacture in England, and at some point in Paris, and by 1865 had opened a depot at 83 Union Street, Glasgow, followed by a branch at 52 Gordon Street1. Following Singer’s decision to open a factory in Glasgow in 1867, took back the licence to start manufacturing himself. A factory at 100 High John Street opened, but much of it was destroyed by fire in April 18722. Later that year, a new retail outlet at 60 Buchanan Street opened, and in August 1872, the company applied to the Dean of Guild Court for approval to erect new works3. The new factory, once constructed, was a much larger affair.

The sewing machines were not just intended for home-based dressmakers and domestic use: there were variants for ‘shirt and collar makers, upholsterers and general manufacturers… tailors… boot and shoemakers, saddlers and harness makers’4.

Elias had earlier gone into a short-lived manufacturing partnership with his brother but soon broke off to establish his own sewing machine company (the ‘Howe Machine Company’) with his sons-in-law, developing his own patent improvements. In 1873, the year a new factory opened in Bridgeton, Glasgow, it was Elias’ company that succeeded, buying up Amasa’s company, although Elias himself had died some years before.

Andrew Myles attended the factory’s employees’ soirée in early 1873, where the hall was bedecked with American and Union flags, the largest of which, reportedly 60 feet by 40 feet, was probably then hoisted onto a 120-foot pole, designed by the firm and ‘calculated to sustain the enormous strain of such a tag in a gale of wind’.

In 1874, the factory was producing a thousand sewing machines a week, with the capacity to double that.

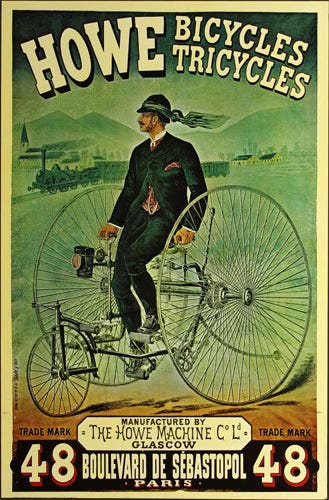

However, whether as a result of competition from other manufacturers, such as Singer, or simple over-supply, within a decade the company had started producing bicycles and tricycles.

By 1887, however, the company’s assets were being sold off, with the company placed in voluntary liquidation in August 1890. A new company was launched the following January and lasted until late 1899, when the Bridgeton factory finally closed.

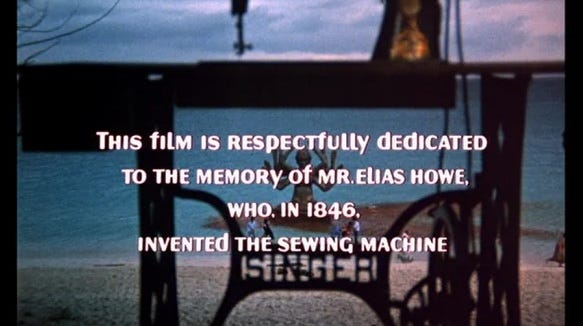

In the end credits of the Beatles’ film Help!, the following credit appears (albeit showing a Singer sewing machine, which was probably more easily available):

The background is an uncorroborated urban legend that Elias Howe once dreamt of being threatened by cannibals. Waking, he recalled how the spears had holes in the shaft that moved up and down, inspiring the vertical stitch innovation and making his sewing machine markedly different from the lockstitch method pioneered by Walter Hunt over a decade previously. In Help! there is a scene where Ringo is slowly encircled by cult members planning to sacrifice him to appease the goddess they worship, hence the reference.

James Kennedy’s family

In 1878, James Kennedy married Mary Dawson (who lived next door to his flat at 42 Raglan Street). They would have one son and two daughters, but within three years James, although still listing himself as a ‘Civil Engineer and Architect’ in the Census, had gone blind. Following Myles’ departure, he had entered into a new partnership in 1875 with William McIlwraith, who had his own practice at 121 West Regent Street, and Robert Brown, who may have been an assistant in the earlier practice, under the name McIlWraith, Kennedy & Brown, but the partnership must have broken up soon after.

In 1891, James was living at the back of a confectioner’s shop at 36 Dumbarton Road. Nevertheless, he and his family seem to have adapted to his disability, and for the rest of his life he worked as a ‘manufacturing confectioner’ and retailer, living at 26 Charing Cross Mansions, then 25 Elmbank Street, before eventually dying of bronchitis in 1903.

Susceptible chests seemed to run in the family: James’s son Dewar Onrust, an apprentice house painter, would die from phthisis, aged 25, as did his younger sister, in 1919, aged 25. James’s elder daughter lived longer, dying unmarried in 1939.

Thomas Kennedy’s family

By 1891, Thomas was back in Glasgow, living at 13 and later 18 Willowbank Crescent. This may have been a belated attempt at reconciliation with his younger brother. For some years he gave his profession as ‘Clerk of Works’, but by 1901 had returned to being an employing architect He died at 235 West Regent Street in January 1913, probably as a result of a heart attack.

Of his one son and three daughters, the son, Alexander Ferguson, became a bank teller, married and had four sons and a daughter. The eldest daughter, Amelia Stewart, became a teacher and married one, and bore nine children, five sons and four daughters. The second, Isabella Dewar (or ‘Belle’) became a ladies’ tailor and in July 1914 married Gustav Adolph Marek, also a ladies’ tailor, at the Grand Hotel, Glasgow. She died from thrombosis while six months pregnant at 2 Vinicombe Street in May 1915, and Gustav developed ‘delirious mania’ and died at Woodilee Asylum, Kirkintilloch, in 1918. The youngest daughter, Marion Ferguson, married James Leslie Dunlop. His mother came from the Gray Buchanan family of Scotstoun while the Dunlops were originally of Tollcross House, but by the mid-19th century James’ father was an ironmaster in Airdrie living at Fullerton House. He died in 1934, she a half-century later in Helensburgh in 1984.

Glasgow Herald, 4 Apr 1865; 1 January 1872

North British Daily Mail, 15 Apr 1872

Glasgow Herald 23 Aug 1872

Glasgow Evening Post, 7 Oct 1870

Story updated to cover Marion's marriage. Her husband's family lived in Tollcross House, Glasgow, for some years, before moving to Fullarton House in Old Monkland (Airdrie).

Another interesting post on the Kennedys, thank you. I'm pretty sure that William MacIlwraith was apprenticed to Angus Kennedy, and was a family friend. His mental health deteriorated and he ended up in Woodilee, where he died in 1909. The practice was sunk in the general collapse of work after the City of Glasgow Bank crash. Towards the end of his life, Thomas had been put out of the house by his wife and was living in a shared room with another old fellow as a lodger. His wife allowed him back home just before he died. I remember Marion, my great aunt, quite well. My brother and I were quite scared of her. She did in fact marry, one James Leslie Dunlop, an extremely wealthy, slightly disabled fellow, from a Lanarkshire family who owned a coalmine, who had a club foot and had a special bicycle made, so that connection is fascinating. They lived in Sandringham in Port Bannatyne, which raises further questions: did he finance that tenement and the Largs one, which I believe were both designed by Marion's father? They sailed a yacht named the Bashie, and the witness at their wedding were Charles Mylne and his wife Janetta, he the brother of Alfred the yacht designer and owner of Port Bannatyne boatyard. On her husband's death Marion received a liferent, administered by Maclay Murray & Spens, but she was already a client long before she met him, and they acted when she took a petition to court after the death of Gustav. I'm sure that there are further stories lurking beneath the surface here.